Words by Johanna Harlow

It’s 1972 and a Ford Galaxie leaves SFO Airport, driving along 101, then winding its way up hilly Page Mill Road. Turning onto a private drive, the car rumbles along the dirt driveway and pulls up outside a rambling farmhouse. Famed bluegrass musician Earl Scruggs and his entourage step out, ready for a remarkable meeting with singer Joan Baez.

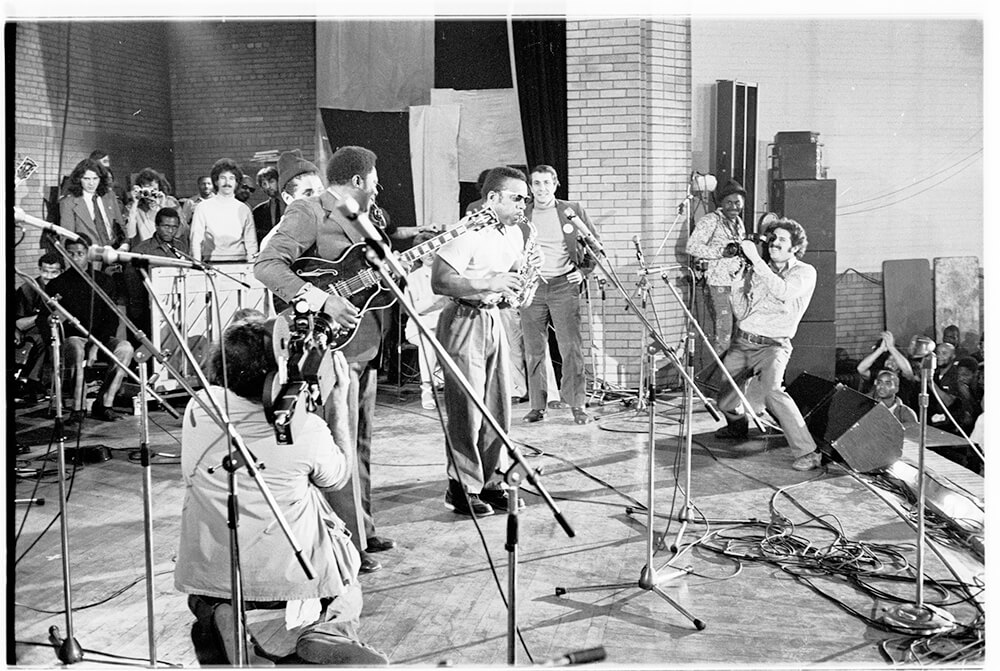

The impromptu musical collaboration that follows is captured by filmmaker David Hoffman in his documentary Earl Scruggs: The Bluegrass Legend—Family & Friends. “Earl is on a personal search,” David says of the film’s premise. “He’s looking at places where banjo can be used in other kinds of music… He’s going to different people he likes, to try to find how his music fits.” Earl’s quest would later air on PBS. “The film was very popular on public television,” recalls David. “In the prime time, it got a very high rating—which surprised the people at PBS, because they weren’t used to country (music) being that popular.”

David captures Earl’s jam sessions with The Byrds, Bob Dylan and Doc Watson, among others. But Earl’s collaboration with Joan is arguably the film’s most powerful. After recently reposting the clip on his YouTube channel, David received over 25,000 likes. What went down on this day on the Peninsula clearly still strikes a chord over 50 years later. But why? To understand, you need to know all the players.

Cover Photo: Courtesy of Raph PH / Photo: David Hoffman

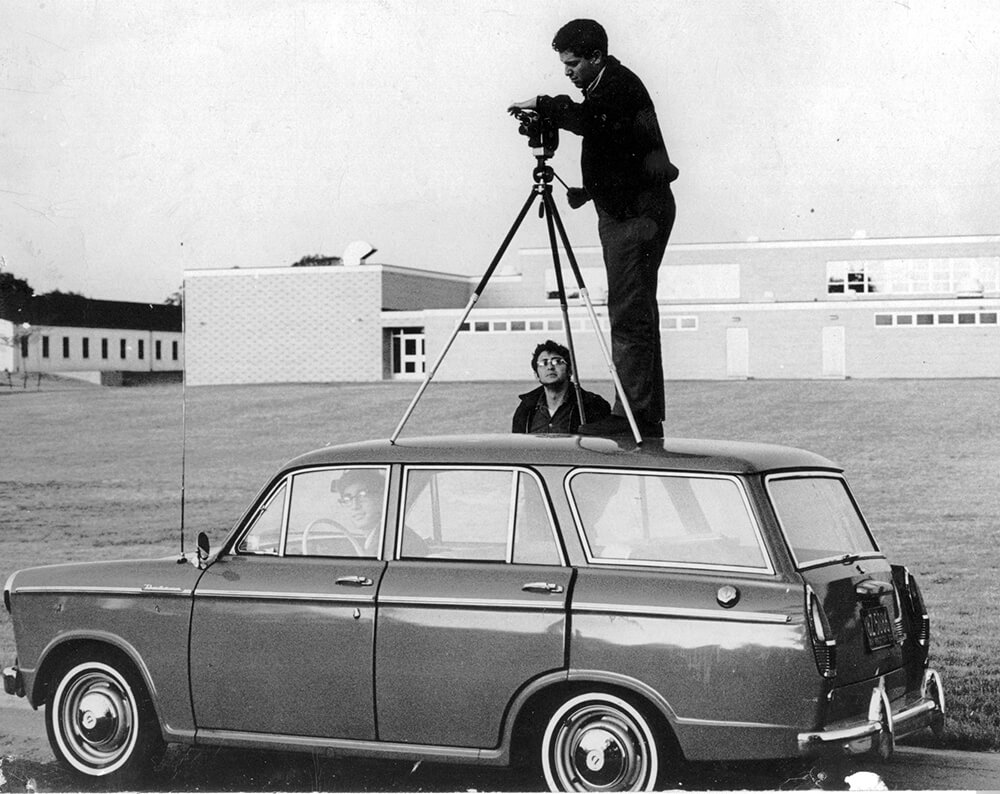

The Camera Guy

Before discussing the legends in front of the camera, take a moment to meet the visionary behind it. A scrappy filmmaker, David Hoffman is the kind of guy who jumps right into the action, hand-held camera at the ready. “There were maybe about a hundred of us in the country who were doing this kind of work—hand-holding, just talking to people,” he recalls. As a documentarian for hire, David has done a bit of everything over his long career. His subjects ranged from competitive inline skating and the military to Wall Street trading and 1960s drug culture. “I had my standards—but you could’ve hired me to do tooth decay, and I would have done a documentary on it,” David chuckles.

That said, his background scored him plenty of music-related projects. “I was a classical musician. I played oboe,” David says. “But then I played banjo and I had a folk song group in college. We played all the Pete Seeger songs. It was a pretty common, rebellious thing to do.”

The filmmaker’s respect for the country genre is evident. “On Long Island, where I grew up, you heard the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday night on the radio,” he describes. “And us music kids, we thought it was unbelievable … I still am mesmerized by the soul of that music.”

d (Photo: Courtesy of David Hoffman

Though David’s films have garnered Emmys, Golden Globes and an Academy Award, he doesn’t put much stock in such things. “Awards don’t mean anything really, you know?” he says with a shrug. “Some of my best films didn’t get noticed at all.”

So what does he care about? “I’m interested in what people think, and the way they express themselves,” he says of his deeply human approach to filmmaking, adding, “My talent is a sixth sense for what people are not saying.”

The Music Man

But let’s get back to Earl Scruggs, the heart of David’s documentary. Back in 1972, North Carolina native Earl had pioneered the bluegrass genre with Bill Monroe’s band, the Blue Grass Boys. He’d also revolutionized three-finger banjo picking (known as “Scruggs-style” today). Despite these contributions, Earl was chasing a more contemporary sound. After breaking with his more traditional musical partner Lester Flatt, Earl reached out to musicians he respected to set up jam sessions, embarking on a journey that would be highly influential in developing his sound as an artist over the rest of his seven-decade career. Along for the ride were David behind the camera and Earl’s musician sons (Randy on guitar and Gary playing bass).

Photo: Courtesy of David Hoffman

These jam sessions, set in the intimate spaces of people’s homes or the freedom of country fields, have an earnestness about them. And so does Earl. “Mensch of a guy, beautiful human being,” David says of how Earl treated artists and film crew alike with respect and dignity.

On his quest, Earl made music with The Byrds on a farm in North Carolina while horses cantered by and a barefoot kid perched on the tin roof for a view of the visitors. He and Doc Watson dragged chairs onto the lawn to strum in the great outdoors. Earl also paid a house call to Bob Dylan, playing as the pendulum of the old wall clock kept time like a metronome. And now, he’d arrived on the Peninsula.

The Legend / Humble Hostess

The East Coast-West Coast divide was evident as soon as Earl and the gang entered Joan’s house. “I’m gonna call it a hippie house,” New Yorker David says of the legend’s modest farmhouse with hillside views and outdoor shower. “I’m an East Coast guy—I’d never seen an outdoor shower!” he notes with a chuckle. “Two extraordinarily different cultures.” As the protest folk singer, the trailblazing country musician and his sons settle onto chairs and an earth-brown couch in the living room and begin tuning their instruments, a sense of anticipation builds. What’s about to transpire?

While their home lives may have looked different, Joan and Earl were united in opposing the Vietnam War. This was a particularly gutsy stance for Earl. “For him to say that is a big deal, because country music was notorious for people being for the Vietnam War,” David explains. “Earl was not highly political, but he was bold.” In the midst of a national draft and seemingly endless conflict, “he wanted the boys to come home,” David reflects. “That’s all he cared about.”

Photo: Courtesy of David Hoffman

Joan and Earl also shared the easy camaraderie of old friends. About a decade earlier, they had met at the Newport Folk Festival, then went on to play together. The first few times the two interacted, Earl had a quiet but sweet line of approach. “He was so shy,” Joan recalls. “He used to come up and say, ‘Remember this one?’” Then he’d launch into a song on the banjo and wait for her to join in. “I had reason to be shy,” Earl protests. “I admired your singing so very much.”

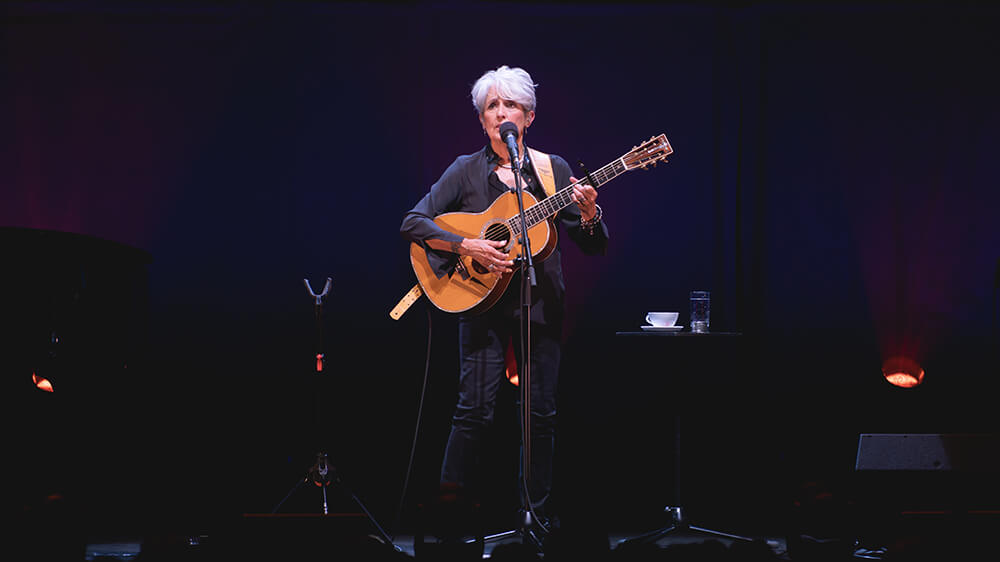

And then Joan, strumming her own guitar, starts to sing. “Her voice.… it gets you,” David says. “Joan, you’ve got to understand, was overwhelmingly powerful. Her presence, the way she spoke, the way she sang, her decency, it overwhelmed me. It overwhelmed all of my film crew.” As Earl, Gary and Randy began to play, the warmth of their music complimented the alluring lilt of Joan’s vocals. “It worked,” David says. “And I was fortunate enough to witness it.”

Human Harmonized

But this musical meet-up was bigger than the songs performed that day. Perhaps what resonates with the current-day viewers of David’s film are all the spontaneous and delightfully human moments sprinkled throughout. While singing ex-boyfriend Bob Dylan’s hit song “Love Is Just a Four-Letter Word,” Joan breaks into her uncanny Dylan impression. After, she pulls her baby Gabriel onto her lap—and he promptly wraps chubby fingers around the microphone before gumming on the mouthpiece.

Halfway through the session, Joan divulges that she had a crush on Earl years earlier. With girlish glee, she recounts the time she gave a concert with Earl, then gushed about him to a stranger in the ladies room. “I said, ‘Oh gosh, this guy Earl, he’s just so far out!’” The woman turned out to be Earl’s wife Louise Scruggs. “I said, ‘You lucky bum!’” Joan recalls with a smile.

Despite her lofty reputation, Joan is gracious with Earl’s less-experienced sons. There’s a sweet moment when she gives an appreciative nod to Earl’s 16-year-old son Randy, recognizing his talent. “She looks at him like, ‘Whoa, who are you, kid?’” David recalls. The teen would go on to become one of the great Nashville backup musicians, winning four Grammy Awards.

At the end of the session, Earl’s oldest, Gary, dedicates a song to Joan’s husband David Harris, who was serving prison time for refusing to report for military duty after being drafted. The compassionate moment and tender lyrics of “If I Were a Carpenter” ends the session on a sweet note.

“Save your love through loneliness, save your love through sorrow,” Joan and Gary harmonize. “I gave you my onliness, give me your tomorrow.”

“We knew we had recorded beautiful moments, casual moments,” David reflects.

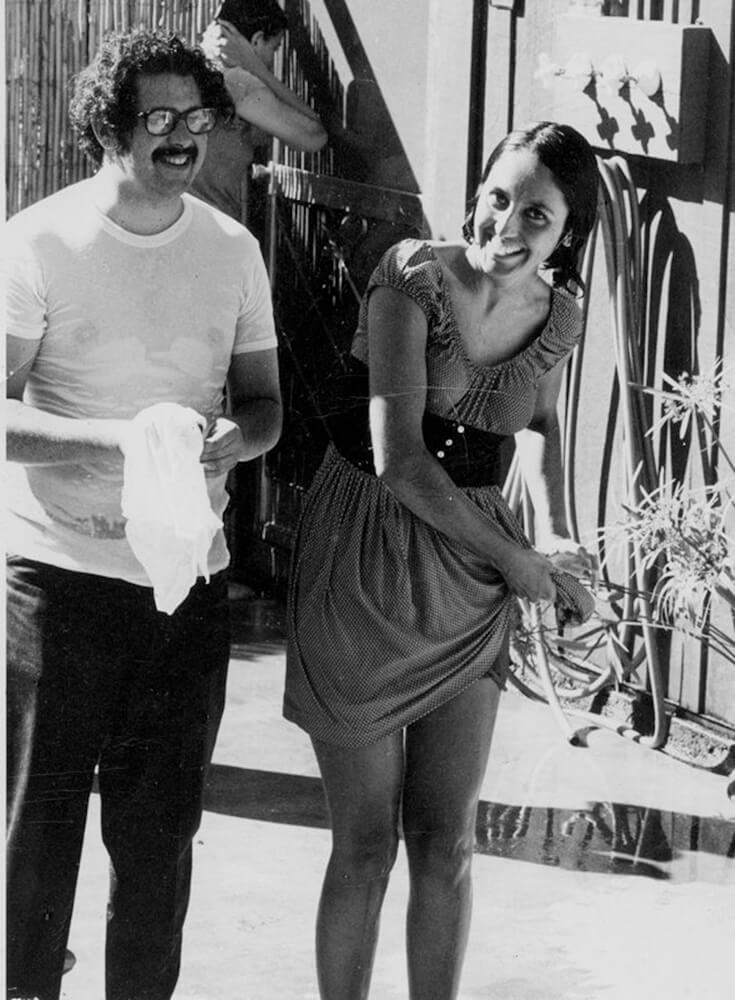

Joan Baez's outdoor shower was a foreign concept to East Coast filmmaker David Hoffman. When she invited him to try it out, he went in with his clothes on. Joan, finding this hilarious, joined him while also fully dressed. (Photo: Courtesy of David Hoffman)

The Road Ahead

Fueled by his quest for a new sound, Earl thrived in the years that followed. This boundary-crossing artist would go on to win multiple Grammys and be inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. He and his sons, performing together as The Revue, would be recognized as pioneers of the country-rock genre. At the age of 79, Earl would be presented with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

As for David, that East Coast guy now lives in Santa Cruz. In recent years, the filmmaker created a YouTube channel, where he’s connected with new audiences by releasing old clips from his past projects. Even at 83—months after surviving a stroke—he continues posting videos twice a day. “It’s a wonderful community,” David says. “I read almost all the comments.” His more than 1 million subscribers would suggest that the feeling is mutual.

And how about our local legend Joan? Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the now Woodside-based protest singer is still pouring herself into music and political activism at the age of 84. Recently, she was honored at the 30th anniversary of the Sweet Relief Musicians Fund in San Francisco, performing alongside a dazzling lineup that included Bonnie Raitt, Taj Mahal and Emmylou Harris. Working the stage, she shook a tambourine during one tune and sang alongside Jackson Browne on a piano bench for another. She closed the evening with a rousing performance of “Diamonds and Rust,” with her grown son Gabriel playing percussion.