words by Silas Valentino

Part of Elizabeth Mitchell’s job is to become unstuck in time. As a curator for Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center, she’s constantly referring to the past when reviewing possible new additions to the collection. How could this piece relate to another already in the archives to form a conversation or, better yet, an argument? As she cross-references, she mentally ticks through the museum’s database stored in her memory.

She also thinks decades ahead, prearranging exhibits for 2030 and beyond that assemble the pieces she’s spent years acquiring into a cohesive array. When considering a potential artwork donation, Elizabeth interprets art history before turning to forecast its future, and all the while the Cantor rests in the present with its ever-beckoning walls awaiting.

“Part of my job is collecting for now and then part of my work is determining if this will be interesting in 50 years,” she says. “After I discovered what a curator does, I didn’t know what else I could do. You’re thinking like a historian but also thinking visually. Thank goodness this weird little job is here.”

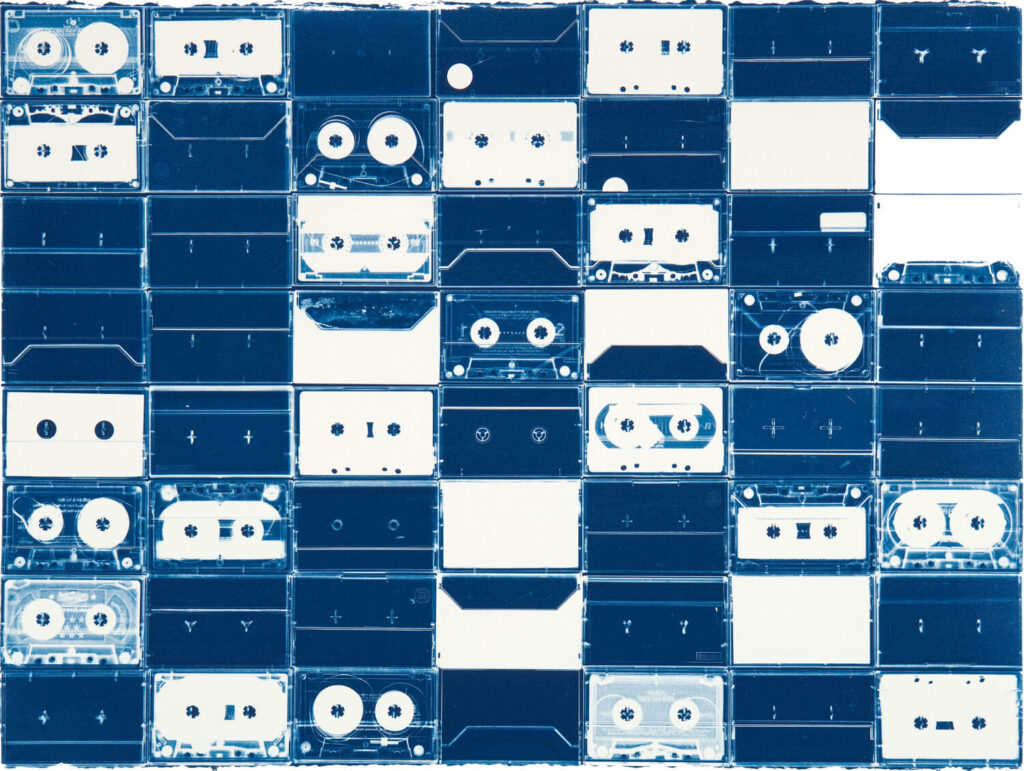

Elizabeth joined the Cantor in 2010, where she is the Burton and Deedee McMurtry Curator and director of the Curatorial Fellowship Program for the museum. As she marks her first decade of curating, she’s on the eve of rolling out Paper Chase, an exhibit opening on April 3 featuring over 100 works done on paper (prints, photographs and drawings) that she and the museum have collected during her tenure. Some of these pieces have been held in reserve, anticipating their inaugural display.

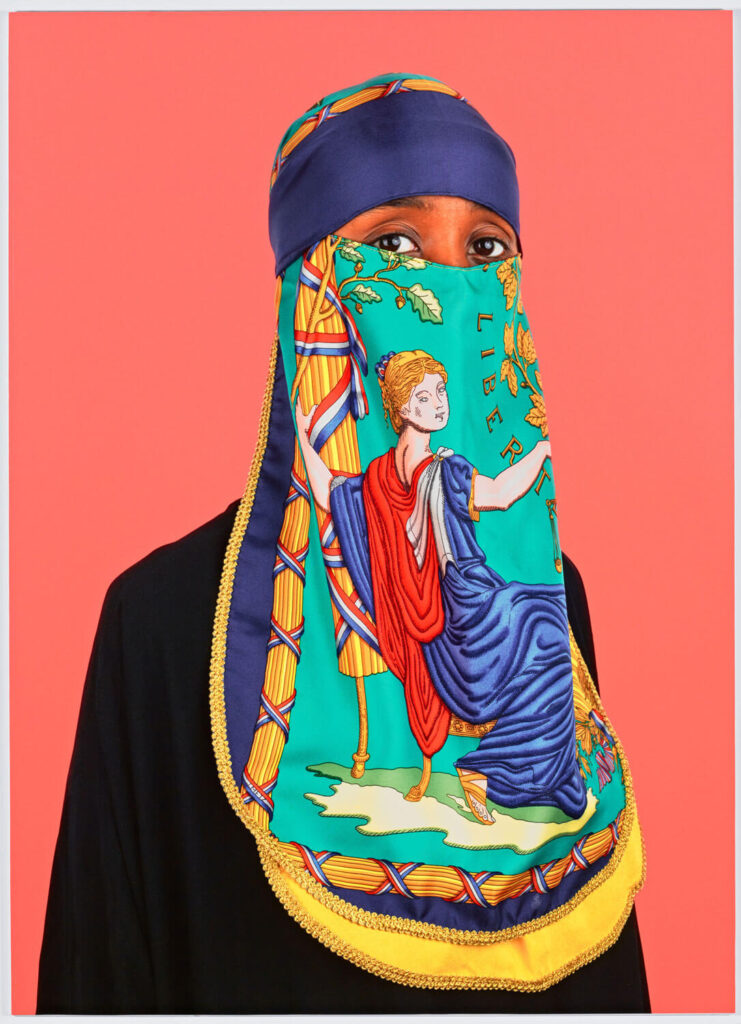

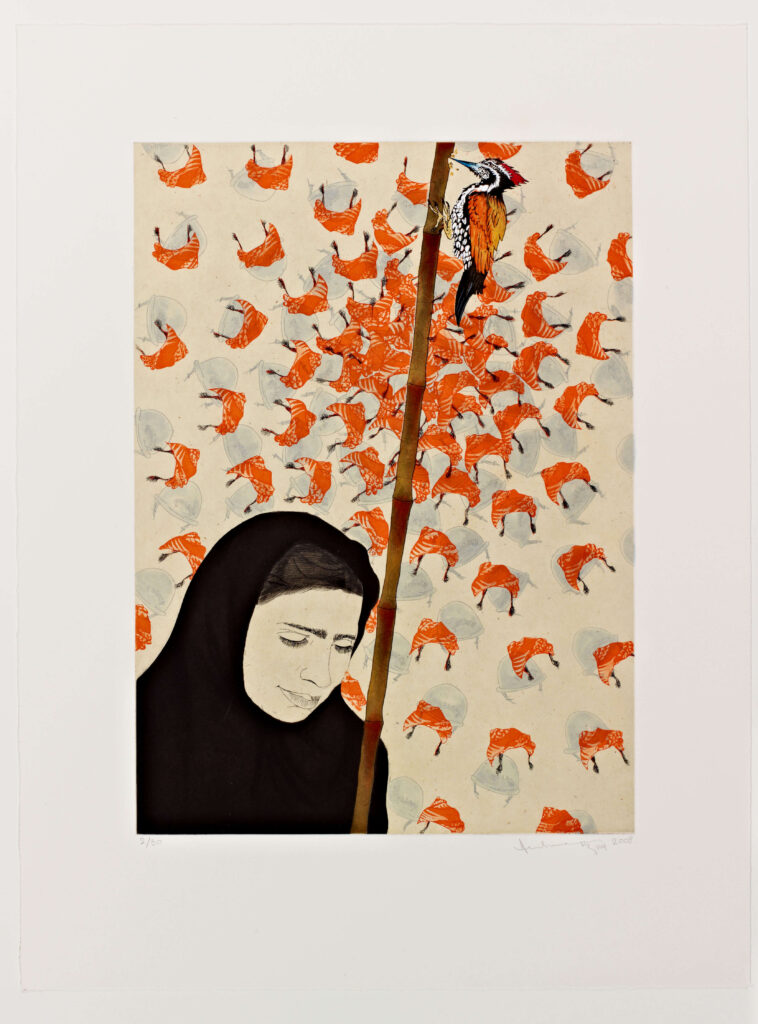

“Looking back at what I’ve acquired, it was really interesting to stop and think about what we have done in the last 10 years. It feels to me, as we’re getting a little farther away from the 20th century, we can now start to define who we are,” Elizabeth says. “I thought it would be interesting to survey something from the 16th century to yesterday. That really got me thinking about different categories I could use to organize. I started with the section that thinks broadly about different identities and how we project them. This first section will look at age, religion, sex and relationship status—all these ways in which we define ourselves.”

The show is grouped into themes: women’s lives, fashion and identity, political responses to war, nature and science. Elizabeth hopes the display will ignite questions around collecting and why the Cantor collects.

“It’s a strategy in museums to show off what’s been acquired and to honor the donors who have been so generous to give,” explains Cantor’s director, Susan Dackerman. “Hopefully, it can inspire other people to collect and encourage a relationship with the museum. This kind of show has a real objective behind it.”

The museum was the recent recipient of a gift donation that included photographs from environmentalist Andy Goldsworthy. Elizabeth was struck by his interpretation of nature and immediately placed the work against photographs they had by Ansel Adams.

“I can look at one photograph and think of 20 different things,” Elizabeth says. “When I go to someone’s house to look at their collection, I start to think how this can go with that. I’m constantly thinking of what kind of conversation we can have.”

A museum is defined by its wall space as well as its storage. Presently, the Cantor has about 40,000 objects in its collection but a vast majority is kept in storage, safe from damage and potential thievery.

“In museums across the county, only two or three percent of a collection is on view at one time,” Susan says. “One has to be precise in terms of collecting practices. Things have to meet a certain criterion. The most complicated storage challenges are around the scale of things. Think of the Rodin bronzes we have here—it’s easier to keep them on view than to put them in storage because they’re so big.”

A team of registrars work in and out of the storage facility to maintain the art’s security and to retrieve specific pieces requested by students and faculty. The Cantor’s mission is to educate and most of the pieces in its micro-encyclopedic collection are available for viewing in any of the museum’s study rooms, which can be refashioned into miniature galleries.

“There’s a myth that the storage in a museum is a locked door and no one goes in and out but it’s really like a beehive. You can only see a few bees,” Elizabeth says. “Nothing is forgotten; things are just used in

different ways.”