words by Silas Valentino

A unique Peninsula town may slip away for good, and its obituary might read like this:

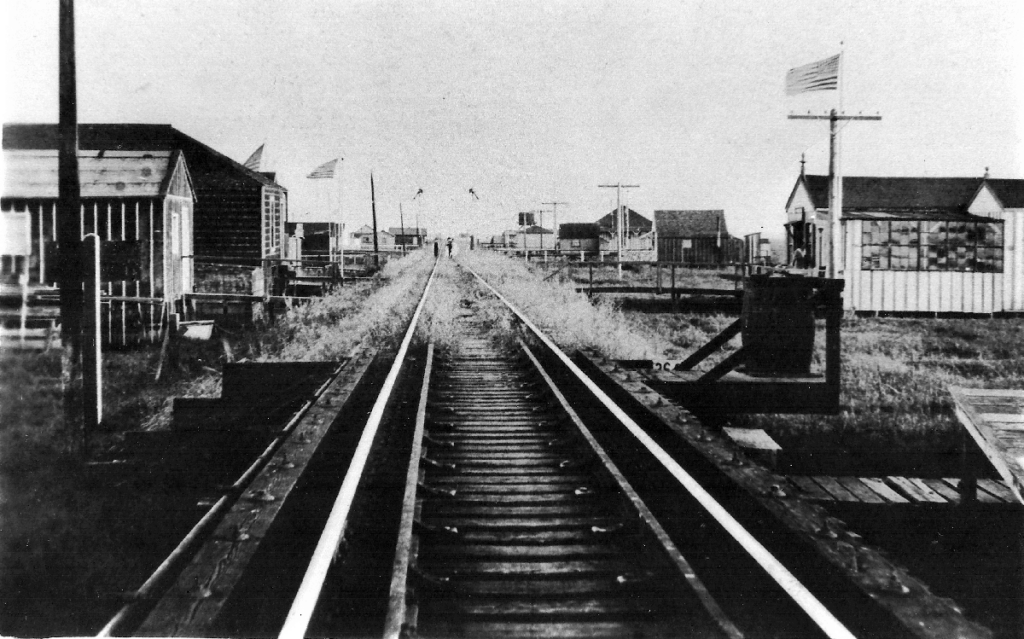

Drawbridge, California, a once thriving town built on wetlands, a Venice in the sloughs at the southernmost tip of the San Francisco Bay where its main street was the railroad track and sidewalks were a channel of wooden planks that rose above the tide to create a floating community, died after a long, lingering battle with relevance. It was 144 years old.

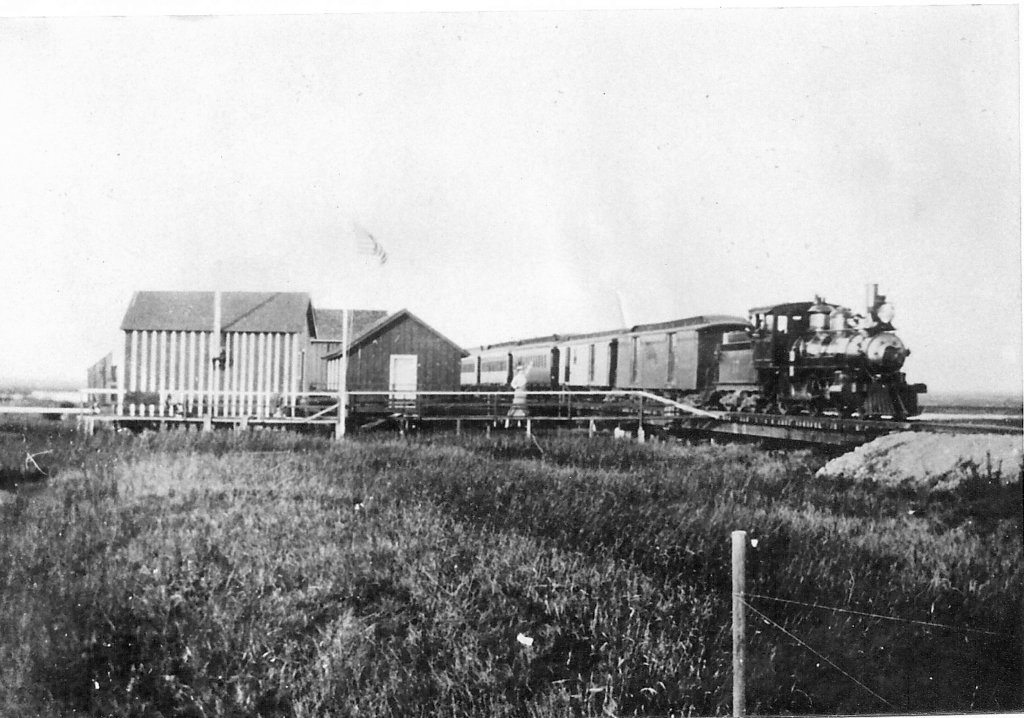

Drawbridge was birthed by train in 1876 to become a community on the Peninsula unlike any other, past or present. Its creator may now become its destroyer as a new proposal for expanding the railway would mean certain destruction.

Nearly a mile long and 80 acres in size, Drawbridge was built as a link through the mudflats and sloughs for the then-new South Pacific Coast Railroad. The train, forever its main and sole artery, shepherded in a community that rose and fell like the daily tides.

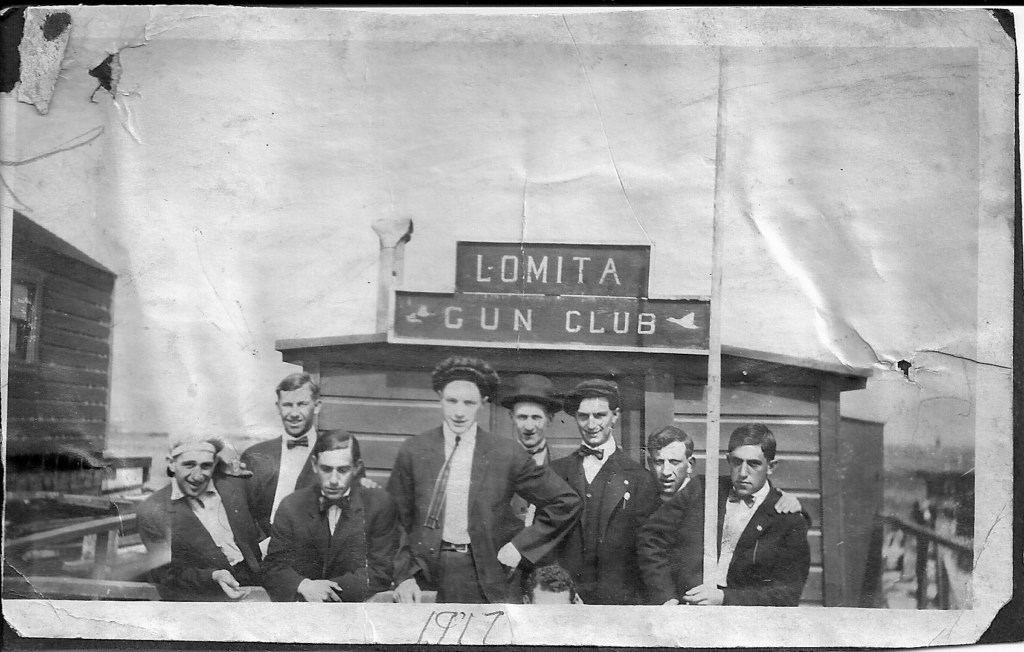

First was the lonely bridge tender who had to hand-operate the two drawbridges for boat passage. Then came the duck hunters and weekenders. The town flourished as an Old West Mecca that peaked in the 1930s with close to 90 buildings, including a pair of hotels and many waterfowl hunting clubs. With neither government nor law enforcement, the wild town was rife with gambling and bootlegging throughout the first half of the century. But environmental conditions deteriorated, leading to an exodus and abandonment by its last full-time resident before the 1980s.

Drawbridge is now for the birds. Since 1974, it has been a protected habitat for bird restoration. Members of the avian community flock to its muddy and fertile shores where humans are now legally barred from crossing over the two train bridges that bookend the island. Drawbridges no more, the overpasses crossing Mud Slough and Coyote Creek have been replaced a couple of times; Mud Slough is still a swing bridge and Coyote Creek is a fixed trestle bridge.

Nicknamed “Saline City” for its position sequestered between salt ponds, Drawbridge offered an allure for the adventurous and eccentric that resonated for generations.

Today, when the sun disappears behind the Santa Cruz Mountains, a golden hue is cast upon the stiff pickleweed to create a still life picture of serenity. Beyond the calls of the wild geese or the crunch of succulents beneath your feet, the only remaining sound blows in with the wind.

That is, until the thunderous horns from the evening Capitol Corridor commuter train emerge and the modern locomotive rips through the heart of town.

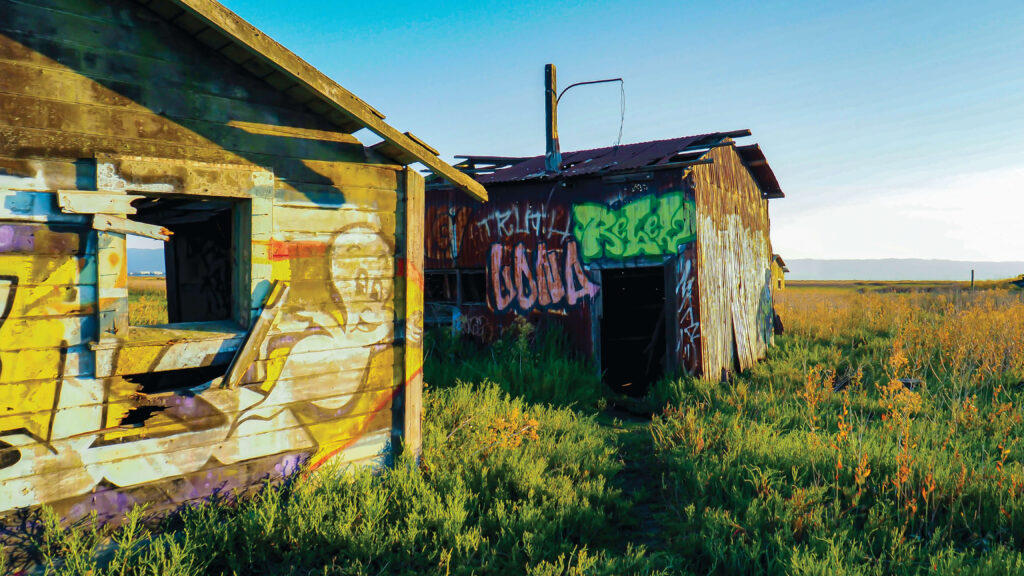

You can sneak a peek of Drawbridge by riding the Capitol Corridor, Altamont Commuter Express, Coast Starlight or passing freight trains. From there, you might catch the yellow and white graffiti image on a decrepit wooden house depicting the town’s unofficial mayor: Casper the Friendly Ghost.

Absent of human presence but enshrined in its history, prints of humanity remain in the roughly dozen structures still standing but slowly slipping into the slough. As part of the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Drawbridge can be viewed on foot from a vista point at the Mallard Slough Trail Spur, a couple miles from the Refuge’s Environmental Education Center on the outskirts of Alviso.

Traversing across the still-active bridge train tracks onto the protected island is illegal and unsafe. Trespassers on federally-managed land may be penalized with fines. However, perhaps in the spirit of Drawbridge’s lawless past, trespassers continue to skulk onto the island to have their look at this historic oddity.

The ghost town’s appeal ranges from urban explorers to history buffs. Dr. Cecilia (Ceal) Craig is president of the San Francisco Bay Wildlife Society and co-wrote the book Sinking Underwater: A Ghost Town’s Amazing Legacy along with Anita Goldwasser in 2018. Ceal leads an occasional historical excursion out to the Drawbridge vista point. (These are now virtual tours with COVID-19 restrictions.) With each tour, interest in the town is resurrected.

“Most questions are about what it was like to live there,” she says. “People try to compare it to their own town—what would it have been like to live in simpler times with no toilets, no septic tanks and the tide coming in twice a day?”

In the beginning, it was much like how it is today. Quiet and calm. The train only stopped on Sundays in 1876 and the bridge tender occupied the sole building on the island. He’d charge duck hunters half a buck for a night’s stay in his home. Within a decade, local newspapers started to write about the secret hunters’ den and by 1890, construction of other buildings began.

The island was officially christened Drawbridge with a white sand paint sign hoisted at the bridge tender’s shanty as weekenders began to arrive in droves. The Sprung’s Hotel opened in 1900 to accommodate them. It’s speculated that the population reached its height during the 1920s with around 600 people congregating during the weekends.

But as Drawbridge expanded, so did the surrounding Bay Area. Salt companies began to build levees and drained the marshes. Water pollution from sprouting nearby cities started to spoil hunting and fishing while freshwater became difficult to secure. By mid-century, newspapers began classifying Drawbridge as a ghost town (even though a few residents remained), which attracted vandalism, looting and burning of the abandoned cabins.

In 1979, Charlie Luce, the final resident, pulled up stakes. Drawbridge—Population: 0.

Altamont Corridor Express, a commuter rail service connecting Stockton and San Jose, is proposing adaptations for the railway in the Alviso Wetlands to improve the Central Valley commute. They published their alternative studies report earlier this year wherein three of the four options call for building new sets of railroad tracks through present-day Drawbridge.

“The only way I can see that work is if they take down the buildings,” Ceal says, adding that the San Francisco Bay Wildlife Society has already submitted its formal comments on the proposal and that the project has yet to be approved.

However, the modern-day Drawbridge tender isn’t crying doomsday.

“As much as I love learning about it, I just can’t justify saving Drawbridge over having better commuting capabilities,” she reasons. “I would like to do one more deep study on it and take pictures to see what’s there before we close that chapter. As long as there is a way to put those new bridges in that doesn’t hurt the habitat or refuge as a whole, I can’t say, ‘Don’t do this to Drawbridge.’”

Ghost towns are testaments to our inevitable demise. However ephemeral, they celebrate the fact that we did indeed exist. They draw us into their fading light for a glimpse of yesterday and after we return to the present, we’re humbled by the tenuous nature of our own mortality.