words by Sheri Baer

Her official title is Director of Museum Collections, but functionally, Julie Bly DeVere is also a detective. She has to be, given that her single-minded focus is Woodside’s Filoli House, the stately centerpiece of one of the Peninsula’s finest remaining early 20th-century country estates. “You want it to feel like it did when it was a home,” Julie says. “To experience that moment, that walk back in history.”

For Filoli, that history spans two families: William Bowers Bourn II and Agnes Moody Bourn (1917-1936) and William P. Roth and Lurline Matson Roth (1937-1975). Tasked with evoking the look and feel of what it was like to live in the 56-room, 54,256-square-foot house, Filoli’s curatorial and interpretive teams confront significant challenges:

• Predominantly recognized for its 17th– and 18th-century English and Irish antiques, Filoli’s original collections drew from 20 cultures and 600 years of furniture and art history.

• When Mrs. Roth donated Filoli to the National Trust for Historic Preservation back in 1975, the house had essentially been cleaned out of its furniture, artwork and decorative items.

“There were two auctions historically,” Julie recounts, explaining how the Roths purchased Filoli fully furnished but sold off pieces that didn’t fit with their own aesthetic. “The 1937 auction was described as ‘A Treasure Trove of a Lifetime of World Travel Never to Be Gathered Again,’” she says, “and then in 1975, Mrs. Roth had another auction before she realized that she wanted to donate the house and that eventually the house would become an historic house museum.”

The largest sale Butterfield & Butterfield of San Francisco had conducted to date, the 1975 auction required four days for the furniture and four days for the library. “It was advertised as a collector’s dream,” cites Julie. “We lost the huge majority of the furnishings throughout the house, and most of the pieces lost in the sale are still out in the world waiting to come home.”

And thus, the vital need for detective work—to tirelessly hunt down, restore or recreate Fioli’s treasures and make the house as authentic as possible, a truly “livable” museum.

When Filoli first opened to the public as a National Trust for Historic Preservation site, it was only for garden tours. “I think everybody was pretty curious about what the inside of the house looked like,” Julie says. “Mrs. Roth even complained in those first few years that every time she came over she would see people’s face prints on the windows from trying to peek in.” The historic house began to allow visitors as early as 1978, with great attention given to the property’s wall coverings, marble fireplaces and vaulted ceilings. “According to my predecessor Tom Rogers, we talked a lot about architecture,” notes Julie, “because the rooms were largely empty.”

To fill the house, Filoli turned to loans from the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. After donating the property, Mrs. Roth continued to visit Filoli and is said to have remarked, “It’s odd when the house is filled not with the things that you recognize; it doesn’t have that same sense of home and that same sense of place.” With her death in 1985, Mrs. Roth stipulated that original Filoli furnishings still in her possession be returned to the house and more donations followed—from other Bourn and Roth family members and even family friends who had purchased pieces at Filoli’s auctions.

By the time Julie joined Filoli in 2011, the focus had begun to significantly shift—from “filling” the house to building a permanent collection of original and period furnishings. “Today, we focus on studying inventories and photos and try to recreate the rooms as close to what they were at the time the families were here,” Julie says. “We want it to feel like it did when it was a home.”

That’s where the detective work comes in. And there’s no shortage of sources—starting with Filoli’s archives, spanning 63 linear feet of newspaper clippings, magazine articles, blueprints, inventories, auction catalogs, letters and legal filings. Regional archives yield nuggets too—not to mention the 8,000 books in Filoli’s house libraries and curatorial library, along with family and staff interviews and oral histories. “There’s about 5,000 photographs so far,” adds Julie, “and we’re still scanning; there’s probably another 10,000 slides that have yet to be scanned and catalogued.”

Filoli dates back to 1917, so there’s also the matter of choosing which era—and even decade—to focus on. “That can be the hardest thing to decide because we had two different families living here,” Julie says. “We ask ourselves, ‘What stories do we want to tell and what objects do we have that support those different stories?’” As illustrated by the following restoration projects, once a decision is made, then it’s a matter of chasing clues and solving the right mysteries to bring each Filoli chapter back to life.

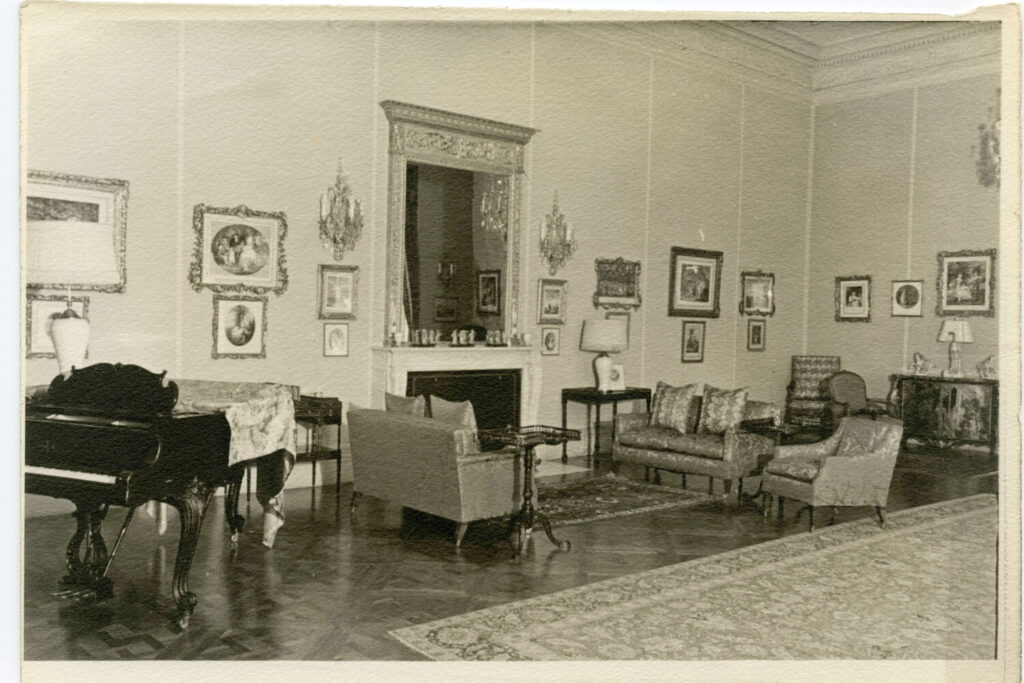

The Drawing Room

“This was probably the least historically accurate room,” Julie says of Filoli’s most recently completed restoration. Derived from the phrase “to withdraw,” Filoli’s drawing room is where the ladies would gather after dinner, leaving the men to enjoy their drinks and cigars. “It just felt wrong when you walked through it,” Julie explains. “It felt like a big hallway instead of a space that you want to linger in and have tea and listen to the piano and walk around and see the art.”

Guided by some 30 historic images and a 1936 “down to the ashtray” inventory, the Filoli team, with donor support, embarked on a top-to-bottom restoration, from rewiring the twin Louis XIV design crystal chandeliers to refinishing the Louis XV parquet-patterned floors. With the return or replication of signature objects and furnishings—fuchsia-upholstered sofas, a late 19th-century Steinway piano, Qianlong period Chinese enameled porcelain vases—Filoli’s 35-foot-long elegant salon-style drawing room began to reappear.

However, the room was missing one defining element—the most memorable hallmark of the space. “Originally, Agnes Bourn selected roughly 40 mezzotints to display; they were sort of a collectible late 17th- through 19th-century poster of the day,” Julie says, “and Agnes pulled together a lovely, very curated collection.” The 1936 inventory meticulously detailed every mezzotint: “We knew the artist, the title and engraver of every piece on the wall, and so that gave us a shopping list to scour the world’s art market.”

Partnering with donor Brad Parberry of San Francisco’s Cavallini & Co., the hunt began in December 2018—with 37 mezzotints secured to date, custom matted and framed and returned to their original positions in the room. “What comes across is that Agnes chose to surround herself with beauty,” Julie observes, “images of women and children and scenes of garden and home life.”

The final step in the restoration is just wrapping up, changing the drawing room’s contemporary cool grey-green fabric wall coverings back to their original color—a warm, buttery yellow with gimp trim. “It’s going to sort of glow like Midas,” says Julie, anticipating the sight. “I love when you get to walk back into the room and see it as it was intended; it feels like a sense of wholeness coming back together.”

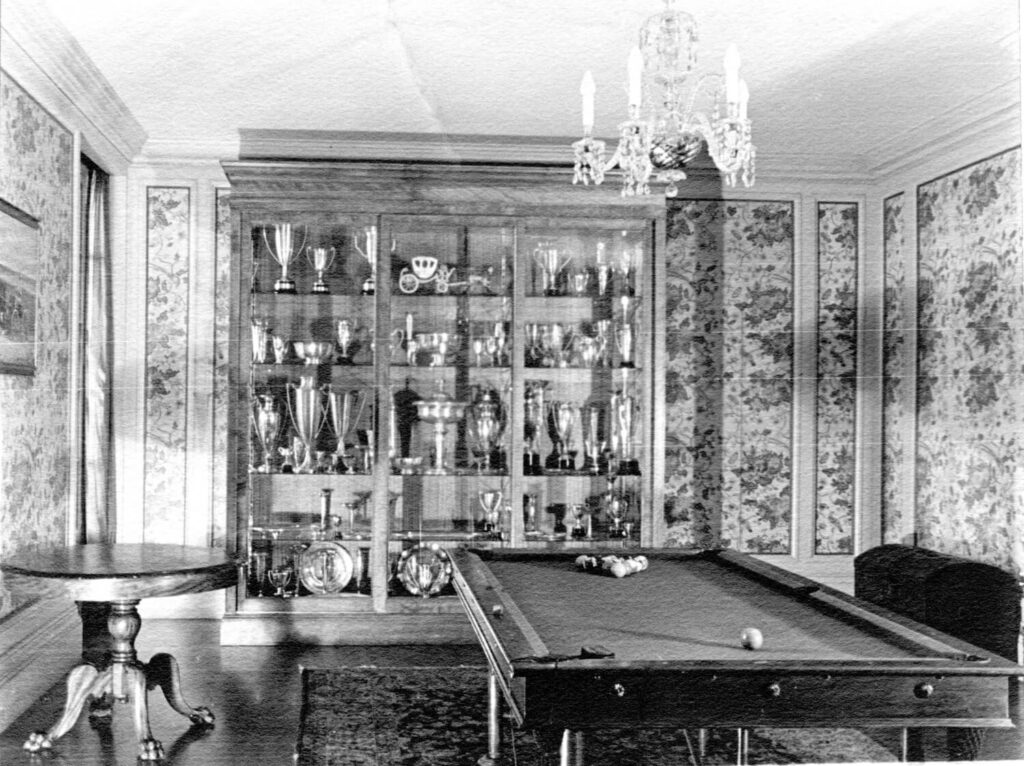

The Gentlemen’s Lounge

With the completion of the drawing room, the next project gets underway. “Now we get to fully dive into the gentlemen’s lounge,” Julie excitedly shares. Converted into a trophy room by Mrs. Roth, the space showcased horse show trophies and awards but no original furnishings. “We often had Mrs. Roth’s carriage sitting in the middle of the room,” Julie says, “so it felt more like a gallery space because the family obviously didn’t keep a Viceroy carriage in their home.”

With a bow-tie inlay in the oak floors, the original intent of the room was clearly a gentlemen’s lounge, where Mr. Bourn would retreat with his friends. Mr. Roth enjoyed the masculine space as well, with inventory records and photos showing a card table, leather club chairs and a billiard table. Restoration began with the reintroduction of the room’s original Baccarat chandelier, found broken and hanging in an upstairs bedroom.

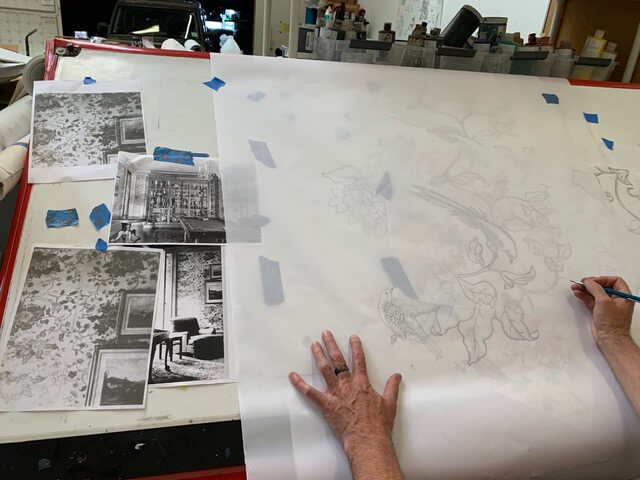

And while original and period furnishings and floor refinishing bolstered the room’s authenticity, there remained some unfinished detective work: the original wall coverings.

Damaged by plumbing leaks and replaced with a modern striped linen fabric, the only two historic photos convey a stylized floral silk wallpaper. “The photos are both black and white,” Julie says, “so I was constantly interviewing Roth family members saying, ‘Do you remember the room in the ’50s? Can you give a sense as to what color it may have been?’” The only clue Julie was able to glean was “a sort of peach.” Then, in the final process of a top-down inventory of Filoli’s closets, Julie discovered an envelope containing little strips peeled off a wall. “I danced in my office the day I found it,” she recalls. “‘This is it! This is the paper!’”

Using the period photographs and recovered fragment, Filoli is working with a wallcovering designer to recreate the original pattern and fuchsia, baby blue and peach color palette, the finishing touch on the room’s restoration. “Some of the peony flowers are larger than my head,” exclaims Julie. “This was a bold room for a gentlemen’s lounge.”

The Family Room

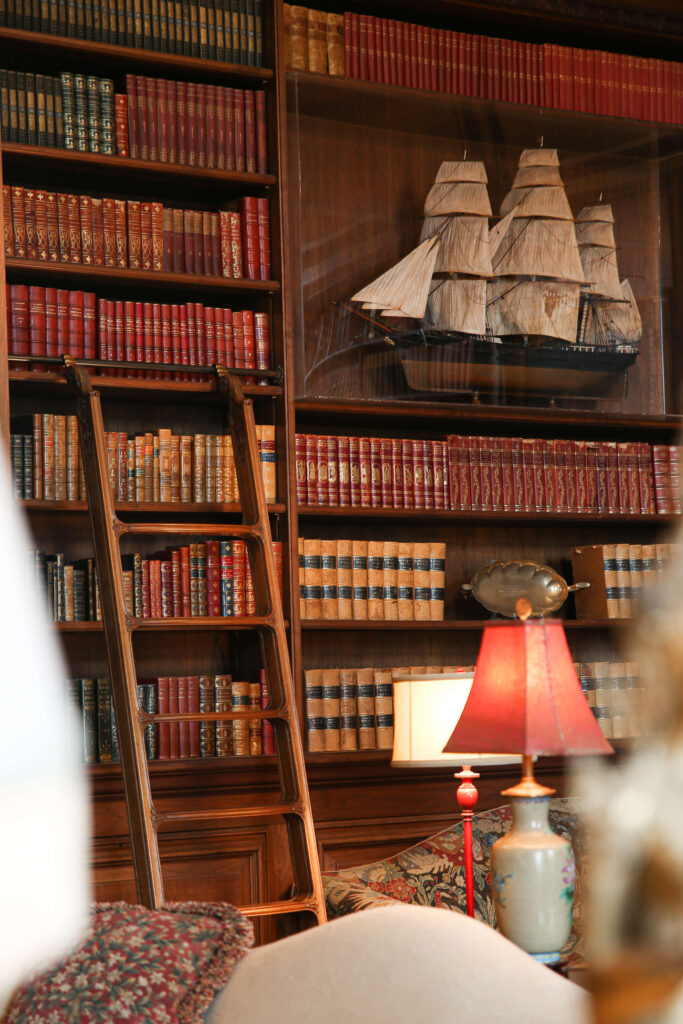

Although the Roth family enjoyed throwing big lavish parties at Filoli, they spent the majority of their time in the smallest room downstairs. “We know that the family room was their favorite,” Julie recounts. “Filoli has 20-foot ceilings so the rooms got cold. The family often tells me that they fought over who would get to sit on the bench in front of the fire.”

With donated Roth family portraits hung in their original spots, the room presented an ideal opportunity to share Roth-era stories with visitors. The sole heiress to Matson Navigation Company, Lurline Matson Roth married William Roth, who guided the family business into the building of luxury cruise ships and Hawaiian hotel properties. “We want to show the room as it appeared during the 1960s,” Julie says. “We have a lot of historic views of the room from that period.”

Like other Filoli restorations, it’s all about the details: “Everybody was smoking in that period, so we have Zippos on the table, Mr. Roth’s cigars being brought out, a bridge game with an ashtray at every corner as well as a drink.” For the Roth family, the drink of the house was Jack Daniel’s. “This was the birth of California casual that you would make your own drink,” Julie says, “rather than your butler serving drinks to you,” referencing the room’s well-stocked wet bar, as well as a vault the Roths converted for upstairs wine storage. During the shelter-in-place orders, she personally refurbished a 1960s Zenith TV, similar to the one the Roths owned. “It looks great in the space,” she says. “I wanted a television in that room for nine years, so it was really exciting to finally get one that fits the look and feel.”

Ready for Visitors

Each of Filoli’s rooms strives to capture a family snapshot in time—whether it’s being transported back to the Prohibition Era in the formal dining room or World War II in the kitchen. With new interpretive panels and custom soundscaping further enhancing the feel of bygone eras, now all that the historic Filoli House needs is the return of visitors. The garden and estate trail are currently open with the Filoli team eagerly anticipating the resumption of the property’s indoor tours when San Mateo County’s COVID-19 restrictions lift.

Julie sees parallels to the historic site’s early days, when Filoli’s secrets were lost or locked away—with only tantalizing hints of what was once inside. “I was onsite last week with the sun coming through in the afternoon and I looked at the middle doors of the reception room, and they were just covered in nose prints,” she says. “I just stopped and started laughing; I could almost hear Mrs. Roth telling us that we need to wash that window.”