words by Sheri Baer

The route to Sam McDonald Park is a winding one, twisting and turning from Portola Road in Woodside with a sharp left onto La Honda Road (Highway 84) to Pescadero Creek Road. The sheer act of navigating the tight curves causes one to slow down and absorb the passing scenery. Sunlight streaks down through endless groves of majestic trees, and on this particular morning, steam from recent rains rises from the pavement, creating a mystical, otherworldly effect.

Gently braking to execute a 15 MPH switchback turn triggers musings about making this passage in the early to mid-1900s. That’s when Sam McDonald motored this same stretch of road (under significantly rougher conditions) in a Model B Ford roadster, journeying to his sanctuary in the redwoods nearly every weekend for 40 years.

For many, ‘Sam McDonald’ only resonates as the namesake of a San Mateo County park or ‘Sam McDonald Mall’ and ‘Sam McDonald Track House’ on the Stanford campus. But there’s a reason Sam’s name endures in perpetuity on the Peninsula.

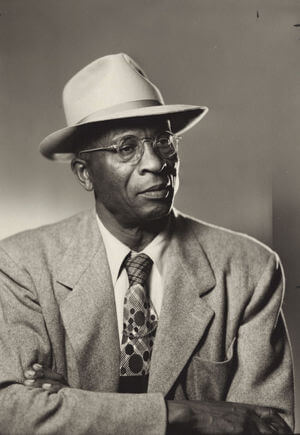

In the years he lived on this earth, between 1884 and 1957, this 6’4” man with a commanding presence earned the status of local legend. The grandchild of Louisiana slaves, Sam forged the way as the first Black person to own property in the redwoods and hold a major administrative position at an American university.

Known for his warm heart, generosity and benevolent spirit, Sam helped shape the future of a world-renowned academic institution and secure the future of his beloved forest—which continues to inspire awe and wonder to this day.

“See my surroundings. Living waters flow, vegetation grows, creatures walk, fly and creep about. Gaze upon these ‘lords of the redwoods’ in their heavenly ascent. You become possessed to feel as majestic as they when your vision rests upon their lofty pinnacles.”

— Sam McDonald – Sam McDonald’s Farm

Sam’s Start in Life

In his autobiography, Sam McDonald’s Farm (a nod to Stanford University’s nickname), Emanuel “Sam” McDonald recounts his humble beginnings in this world—his surname McDonald was taken from the Scottish family that owned the Monroe, Louisiana, plantation where he was born. In 1890, when Sam was six, his family ventured west to Southern California where his father farmed sugar beets and continued to preach. It was here that Sam suffered the tragic loss of his mother. Sam was 13 when the McDonalds made the three-week trek north to the sugar beet fields of Santa Clara County. The first Black family in Gilroy, the McDonalds found employment on the Gubser farm, and Sam quit school in the 7th grade to bring in more money, milking as many as 20 cows a day.

At the age of 16, Sam dramatically altered the course of his life. The McDonalds joined a caravan of families en route to the Pacific Northwest, and Sam found himself back on the trail with his father and brother, Jesse. But as he approached the Oregon state border, Sam had tremendous misgivings about leaving his treasured home. “I became grievously homesick; my mind was definitely made up to return to heavenly California,” writes Sam in his autobiography. “In October 1900, I was off to begin my journey, retracing the route so recently traveled by Father, Brother Jesse and myself. The very thought that I was about to touch the soil and breathe the air of the Paradise that I had resolved never again to desert created within me a spirit of great joy.” Sam’s father and brother continued on to Washington State, and Sam never saw them again.

“I was born in Monroe, Louisiana, on January 1, 1884, the fifth of seven children. My father, Reverend Peter Bird McDonald, was a Methodist minister before coming to California. His father was granted freedom by his young master, who inherited him with a number of other slaves. His father also purchased his wife for $500. My mother was two years younger than father, too young to remember conditions of servitude. She too was born under serfdom; her parents were slaves in Louisiana until the conclusion of the Civil War.”

—Sam McDonald

Arriving on the Farm

On his own at the age of 16, Sam picked up odd jobs and work where he could—as a horse trainer for a while, and then as a river boat chore boy and galley hand. In 1901, he took a horse-drawn bus to San Jose, thinking he’d return to Gilroy, when he heard talk of Senator Stanford’s horse farm. Confident that he could find work there, he walked 18 miles north to Mayfield (later incorporated into Palo Alto), where he would soon become a teamster and a deputy marshal, rising quickly to become a prominent local figure.

Founded in 1885, a year after Sam’s birth, Stanford University was also a fledgling youth at the time, and Sam and the school came of age together. In what would lead to a 51-year career, Sam’s first job at Stanford was working with a mule and plough to excavate land for the Museum. He hauled gravel to build campus roads and kept an eye out as night watchman on Senator Stanford’s stock farm. Sam helped construct Palm Drive in 1904 and watched Mrs. Stanford’s funeral procession in 1905. After the San Francisco Earthquake struck in 1906, he supervised student crews cleaning up and salvaging bricks. In 1907, Sam was officially hired as Stanford’s caretaker of athletic property and then promoted to the title he would hold until his retirement in 1954: Superintendent of Athletic Buildings and Grounds.

Creating a Stanford Legacy

For Stanford students, Sam became synonymous with the campus—and he made Stanford his home in every regard. At first, he created living quarters in the training house under the school’s original 12,000-seat stadium. Then, in 1909, he converted the Track House attic into his permanent Stanford address, and three generations of students knew they could always find him at the corner of Galvez and Campus Drive.

Sam shepherded a herd of sheep to keep the campus grounds neatly mowed and planted a campus garden that drew the attention of Mrs. Herbert Hoover. In his role as superintendent, he became a national authority on athletic fields and tracks, earning accolades for the replacement of Stanford’s Angell Field track and his signature method of mowing crisscross patterns onto football fields. In 1919, Stanford’s Convalescent Home for Children (the antecedent of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital) was established in the old Stanford mansion on campus. Stanford became “the only campus with its own charity,” and Sam stepped up to adopt “Con Home” as his personal and philanthropic cause. A lifelong bachelor, he became a frequent visitor and “godfather” to the wards and referred to the children of the hospital as “my family.”

Already known for his barbecues and mass feedings of Stanford students and athletes, Sam was tapped in 1922 to head up the barbecue party and cleanup crew for “Con Home Day,” Stanford’s annual student fundraiser for the Convalescent Home. In 1950, Stanford officially changed Con Home Day to Sam McDonald Day to honor his tireless contributions over the years. This was just one of many tributes he received during his long tenure at the University. When Stanford dedicated Sam McDonald Road in 1939, President Ray Lyman Wilbur remarked, “If I had to run against Sam for president of the University, I’d be mighty afraid of the outcome.”

“Mr. McDonald has been a fixed personage on the Stanford campus, particularly around the athletic fields and the Convalescent Home, for nearly a life span. Thousands have been cheered and helped by him. His pleasing personality, added to his devotion to his work, has given him an enviable place in the roster of Stanford personages. His friends are legion, for his service has been great.”

— Tully C. Knoles, Chancellor

College of the Pacific, Preface of

Sam McDonald’s Farm

Living Amongst the Redwoods

As Sam’s career took off, he saved his money and invested carefully. He bought property at California Avenue and El Camino Real and ventured into the backcountry with his horse and wagon. A deeply religious man, he discovered respite among the giant redwoods, which he called the “lords of the forest.”

In 1919, Sam made his first purchase of land in La Honda. His grandmother was half Choctaw, and when he built a cabin overlooking Alpine Creek, he named it Chee-Chee-Wa-Wa, Native American for “Little Squirrel.” Sam posted his favorite sayings on the cabin’s walls, including “He who has 1,000 friends has not one to spare” and “May your blessings be as numerous as the sands in the sea.” He built a small beach and dammed up the creek, creating a pool he named Lake Moqui, after a Hopi princess. Although he maintained his apartment over the Track House, he began to divide his time between the Stanford campus and his cabin. As the years passed, Sam’s horse and wagon evolved into a 1931 roadster, and he became a familiar sight coming through the town of La Honda.

“I have spoken now and again of my lodge Chee-Chee-Wa-Wa in the redwood forests of La Honda. This has been my home away from the campus for the past thirty-four years, and, the season permitting, I have journeyed there after a day’s work that I might rest and work and meditate and pray in the seclusion of nature’s sanctuary.”

—Sam McDonald

Sam’s Final Years and Legacy

Described by friends as “happy, benevolent and generous,” Sam turned his home in the woods into a weekend and holiday retreat, hosting countless barbecues for Stanford faculty and sports teams. As he describes in his autobiography, which he completed in 1953, “Many are the friends who have honored this rustic dwelling with their presence, and likewise many are the days I have enjoyed my solitude embued with the peace and serenity of these surroundings.”

By the time Sam retired from Stanford in 1954, he owned 450 acres and established the La Honda-Alpine-Ytaioa Reserve, which prohibited logging and hunting and provided “asylum to all wild creatures.” He also owned and operated the local water company and rented out a half dozen cabins on his land.

A Stanford University Hall of Fame inductee, Sam died at the age of 73 just before the 1957 “Big Game.” Having attended the Stanford & CAL Berkeley rivalry game for 50 straight years, his presence still enveloped the stadium. When the Stanford Band performed at halftime, it formed the letters S-A-M on the field.

Upon his death, Sam bequeathed his property to the Stanford Convalescent Home for Children, requesting that the land be used as a park for the benefit of young people. With that intent in mind, San Mateo County acquired the land in 1958 and dedicated it as a park for public use in 1970.

Visiting Sam McDonald Park

Following Sam’s same curvy route up Highway 84, the entrance to Sam McDonald Park appears approximately three miles west of La Honda on Pescadero Road. Now an 850-acre facility, Sam’s namesake park expanded over the years, adding 37 acres of old-growth redwoods saved from logging by a citizen’s group and San Mateo County and an additional 450 acres acquired from Kendall B. Towne. From the parking lot (vehicle entry fee $6) and Visitors Center, you’ll see trailheads leading in all directions. Set your course—whether it’s Heritage Grove, Big Tree Trail, Ridge Loop or Towne Fire Road—and you’ll find towering redwoods, breathtaking panoramic views and verdant meadows. Also tucked amongst the miles of trails to honor Sam’s legacy: three hike-in Youth Camps, which are available for day or overnight use by nonprofit youth groups.

Near the Visitors Center, we catch up with San Mateo County Park ranger Katherine Wright, who describes the unique nature of the park’s experiences. “There’s the giant redwoods, the old-growth forest, and then you walk up through some oak woodland and get up onto the highest part of the park where there’s grassland habitat and chaparral with amazing views of the ridgelines around you,” she tells us. “Sam McDonald features a lot of the different habitats that are in San Mateo County, and you can experience them all in one place.”

A San Mateo native, Katherine spent a good part of her childhood camping in nearby forests. And like Sam McDonald, she now makes her home in La Honda. “I grew up hiking in the Santa Cruz Mountains,” she says, “and I feel like we have that similarity between the two of us, that appreciation for the redwoods.” As a ranger, Katherine works on interpretive programming, which includes helping visitors feel a deeper connection with Sam McDonald. “I knew I wanted to create a hike all about Sam McDonald,” she says, “because I was so inspired by his remarkable story. When he purchased the property, his only purpose was wanting to keep it just as it was. He wanted to create this preserve where he could attain the sense of peace and beauty that you wouldn’t normally get to experience anywhere else.”

Katherine leads Sam McDonald-themed hikes for groups of visitors and has made key highlights accessible anytime through the Outer Spatial app. Guided by her directions, we embark on a three-mile (there and back) walk from the parking lot starting on Youth Camp Trail, which unfolds like a woodsy narrow path through the forest. We wind our way onto Old Uncle Road and note the Youth Camp sites with picnic tables tucked into the groves below us. As we maneuver a series of elevations and descents, we begin to hear the tantalizing sound of trickling creek water. Passing behind a few private residences, we catch a glimpse of red paint through the trees.

Chee-Chee-Wa-Wa. Sam’s cabin. Still there, tucked along the bank of Alpine Creek. Damaged by flood waters, the house is worn down and weathered by time but instantly evokes images from another era. It’s easy to imagine Sam hunkered inside on a cold spring night, jotting down his “chronicles” on a yellow pad, handwritten pages that would become Sam McDonald’s Farm.

There, behind the cabin, out back by the creek, Sam’s presence can be felt grilling up a barbecue to celebrate the Stanford football team after an exhilarating win. When Sam looked skyward, he found replenishment in the very same towering redwoods—as high as 280 feet, as old as 1,500 years. And while Sam only dwelled in these woods for a matter of decades, a fleeting blink of time to “the lords of the forest,” this man of noble heart and stature created a sanctuary where they could live forever.

“It is wisdom itself to find happiness with one’s fellow man; equally so with nature, the bounties of mother earth, and the creatures that walk, fly, and creep, all begetting inspiration.”

— Sam McDonald