Words by Sharon McDonnell

Being a professor of French and Italian literature at Stanford University isn’t enough for Robert Pogue Harrison. He also hosts a podcast offering “the narcotic of intelligent conversation” ranked in the top five on literature globally by Apple Podcasts, and doubles as lead guitarist and songwriter in a rock band he formed with three other literary scholars, whose songs are inspired by the likes of Helen of Troy, Edgar Allen Poe’s Annabel Lee and the whale in Moby Dick.

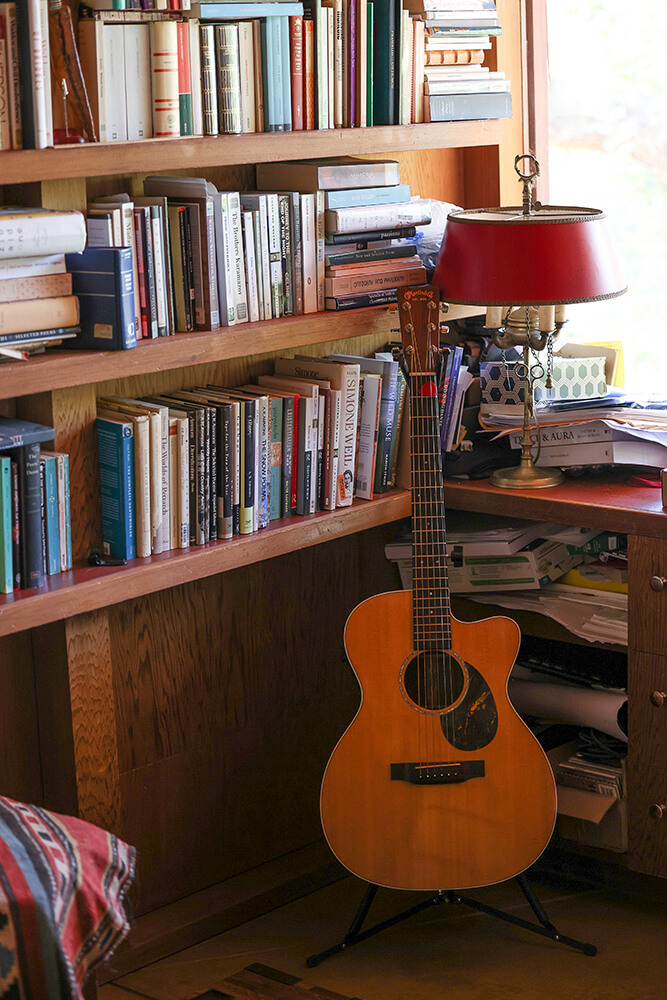

Called the most significant writer in the humanities today by the Southern Humanities Review, Robert has written books about gardens, forests and death, and co-taught a Stanford class on the roots of romantic love—from Plato to medieval Arab love poetry. Born and raised in Izmir, Turkey, and Rome, he’s not dogmatic that his brainy podcast sticks to the classics alone. Past topics include internet addiction, earth-friendly landscape design, bioethics, silence, California writers, particle physics and great narrative endings. He interviews scholars and creatives for his podcast, which always includes songs by his band, Glass Wave, along with classic hits (think: The Doors, Jimi Hendrix and Jethro Tull).

Named a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French consulate (an honor shared with George Clooney, Sean Connery and U2’s Bono), Robert, now 68, joined the Stanford faculty in 1985, and chaired the department of French and Italian literature from 2002-2010. It’s an illustrious career for a man who once weighed two offers after high school: attend college or join a rock band in Italy. An early longform podcaster, he started Entitled Opinions back in 2005 on Stanford radio station KZSU.

Thanks to a tech-savvy graduate student, the podcast became available on iTunes just a few months after its launch—and continues to attract a global (and loyal) fanbase. His band, formed in 2010 with fellow Stanford professor Dan Edelstein and his brother, Thomas Harrison, a UCLA professor, released a CD, accompanied by moody videos, that same year. Since life is infinitely more interesting when you don’t limit yourself to one career (when you can have three), PUNCH switched up seats to pose questions back to this polymath podcast host.

Your podcast often starts with a disclaimer, urging that it should be “avoided by anyone who does not have a high tolerance for thinking. If you’re allergic to the exchange of ideas, if you’re deficient in curiosity, please tune out now.” That’s so refreshing in an era when many people feverishly compete to rack up as many followers and “likes” as possible. Why narrow your audience like that?

Some people say, “Stop doing it.” But I’m very moved by emails from listeners all over the world, often in provincial places, who feel cut off from intellectual conversation and starved for it, and I feel a commitment to them. I have the luxury of a job, and don’t need to make a living from Entitled Opinions, so I don’t need to dumb it down. I have no ads or sponsors. We live in a world where everyone’s always trying to sell you something. I’m not.

How do you select your podcast guests?

It’s much more important for them to be effective communicators than big names. Listeners trust me for the content. It’s necessary to make it worthwhile for them to spend an hour of their time.

When it comes to memorable podcast conversations, who makes your list?

The German filmmaker Werner Herzog, National Book Award winner Shirley Hazzard, and Rene Girard, the late Stanford professor. Girard was known for his theory of “mimetic desire,” a term he coined in 1961, after the Greek word for “imitate.” He wrote, “Our desires are not our own but other people’s desires that we imitate.” He was so prescient about social media, which is all about creating envy, always comparing yourself to other people due to constant posts of photos and brags, that my profile of him in The New York Review of Books is entitled, “The Prophet of Envy.” Peter Thiel, the Paypal co-founder and first investor in Facebook, credited Girard’s class for convincing him of the potential of the online world.

One podcast episode is on silence. You say you practice the “persecuted religion of thinking” in the “catacombs” of Stanford’s basement radio station. How do you view the link between silence and thinking?

Put time aside for silence. It’s a precondition for reflective thought and a dialogue with yourself. Free yourself from the tyranny of the world and its online chatter. Read, read, read. It’s irreplaceable. Books are an inexhaustible treasure horde to enlarge our world.

Letter-writing was the theme of another podcast episode, where your guest was an expert on 17th- and 18th-century France. Can you comment on the brevity of texts, tweets and emails today?

Everything gets impoverished and reduced to the lowest common denominator in what passes for communication today. Letters were once profoundly social, read aloud in salons, treasured and kept. Writing letters was an art form, and they required thought to write. People had to pay to receive letters in France. Rousseau put an ad in the newspaper to stop sending him letters since it cost so much money. Voltaire, the most famous man in Europe in the 18th century, wrote over 15,000 letters.

Your book, Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition, traces their importance in mythology, religion and culture down through the centuries, from the Garden of Eden to Zen rock gardens. How would you summarize the role of gardens?

Gardens are a sanctuary from the frenetic and destructive forces of history, places of care and cultivation that people create to see and hear the oneness of nature. They can go a long way to heal psychic wounds.

Which gardens would you consider your favorites?

On the Stanford campus, the Papua New Guinea sculpture garden, where entire trees were carved by visiting artisans. Internationally, the Villa Cimbrone in Ravello, on Italy’s Amalfi Coast.

What events would you describe as major turning points in your life?

My father died when I was 12, so we moved to Rome, where my Italian mother’s family lived. It left something of a void. When I was 14, I saw Jimi Hendrix in concert. It was hard to be an ordinary bourgeois after that. My brother and I started immersing ourselves in music and poetry and formed a rock band with two other guys. We played gigs in our late teens at clubs and weddings all over Rome. There was a lot of demand since we were an Anglo band.

How did your band Glass Wave get formed?

Dan Edelstein and I decided to bring our musical instruments to class at Stanford, take some well-known songs and change the lyrics to be about Homer, Ovid, etc. Then, we thought it would be fun to compose our own songs. The music or mood came first. Then, we’d think, “What lyrics?” and go into the literary canon to find a match. A mournful melody became Poe’s Annabel Lee.

In “Children of Silicon Valley,” your essay in The New York Review of Books, you inveigh against how people today trade reality for miniature screens. What’s your advice on how to resist the magnetic allure of our electronic devices?

One of the most effective ways is to enter into nature and devise a connection with the natural world in all its full-blown, 3D exuberance. It’s just so comforting. Today the big divide is, do we live in the world or on a 2D screen?