Words by Esther Young

Pragmatic and generous, Panos Panagos refuses to preach about bean origins or soil acidity when visitors enter Alegio Chocolaté in Palo Alto for the first time. Instead, he offers a taste of 100% pure cacao from the African archipelago of São Tomé and Príncipe. “Hold it in your mouth for 32 seconds,” he instructs. As it melts, revealing no bitterness, he tells them, “You’ve never had chocolate before. This is the real thing.”

But before you try for yourself, a friendly note: partake to taste, not to eat. Moreover, it also might just ruin chocolate for you. Pretty soon, you’ll realize you’ve been tasting vanilla as the base flavor in mainstream chocolate. The additive is used globally to mask bitterness—or worse yet, lack of flavor altogether.

How can that be? Panos, Alegio’s lively host, explains: “Blame not the chocolate, but the bean.” A defective bean produces bitterness, he clarifies. According to Panos, most of today’s cacao trees are modern hybrids—more productive, but less flavorful. However, the trees in São Tomé and Príncipe have benefitted from three conditions in the last 200 years: human inaction, monkeys in action and one agronomist who played with the combination.

According to Panos, when Portuguese explorers came upon São Tomé and Príncipe around 1470, they found abandoned islands rich with cane sugar. After importing cacao trees from Brazil, the islands became one of the biggest producers of cocoa by the early 1900s, but went quiet once more when the British Parliament abolished slavery. Indigenous monkeys continued to enjoy the cacao plants, sucking out the white creamy pulp, discarding the pods and spitting the beans back out. The cacao trees—aided by this natural seed dispersal and the island’s humid equator-based climate—flourished.

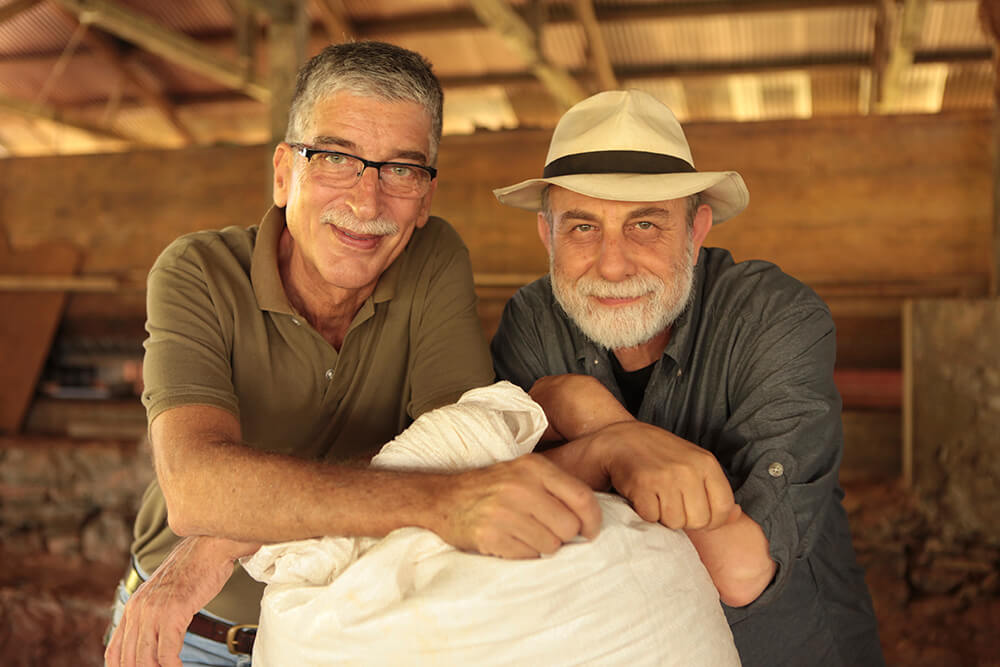

These tropical plants fascinated Claudio Corallo, an Italian-born coffee producer (and Panos’ future business partner) who moved to the islands after war conditions in the Congo (called Zaire at the time) pressured him to leave his home of two decades. In this new setting, Claudio’s curiosity became piqued by raw cacao.

Rather than fixate on the “bean-to-bar” process (an often quipped phrase referring to the conversion of cacao beans to chocolate bars), he took a step back, to encompass soil-to-bar. By refraining from tilling the land, Claudio preserved the island’s rich soil. That led to a discovery: Although the plants produced less than most suppliers, they delivered more flavor to the final product. And that meant they didn’t require other ingredients to mask the bitterness.

This unconventional approach is the reason that Panos, Claudio’s longest-running business partner and his only U.S. distributor, holds court in the Palo Alto shop each day. Although some might be satisfied with the industry standards of vanilla-, lecithin- and milk-infused concoctions, for the chocolate curious and culinary adventure seeker, it’s well worth a step aside.

Signposts appear around the shop with handwritten notes that point venturesome tastebuds towards “slightly reckless” or “faintly dangerous” versions of Alegio’s offerings. With a tantalizing menu ranging from bars studded with pepper and sea salt crystals, rose muscat grapes and crystallized ginger to raw cocoa nibs and roasted beans (“for those who love the purity of flavors”), there’s something for every chocophile.

Panos shares the backstory as you experience and peruse the menu resulting from Corallo’s quest. “He is on a personal crusade to produce the purest possible chocolate that history nearly wiped extinct,” relays Panos. “And he takes no shortcuts.”

Panos first heard of Claudio through a Zimbabwean journalist in the 1980s. While working together in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, “She told me the story of the ‘Italian Indiana Jones’ who was living and working in one of the most isolated parts of the Congolese jungle,” he recalls. Twenty-five years later, after an impromptu cold call, Panos met the character who had captured his imagination.

“We walked single-file through tall and short trees in the rainforest vegetation for hours,” Panos recalls of their first meeting on the island. That evening, they settled in the kitchen of the abandoned plantation home Claudio had restored. “I realized that this guy is my distant cousin who got lost in the middle of the jungle!” Panos likes to joke.

Though not related by blood, both were realists who disregarded fluff and flattery. As they sat in the kitchen long into the night, Panos told Claudio that the chocolate he made was misunderstood. “What you make, this is Rolls Royce,” Panos asserted. Claudio’s eyes lit up. The chocolate maker was not a businessman but through Panos, he could bring chocolate in its pure form to the world.

After initially opening Alegio in Berkeley, Panos realized that nearly a quarter of his customers (including Steve Jobs) were driving from Silicon Valley to visit his shop. Relocating to Palo Alto in 2013 turned out to be a sweet decision, boosting both local demand and Alegio’s online customer base, thanks to the flow of people in and out of the area for business and travel.

“I’m the evangelist of chocolate. Claudio is the demigod,” Panos proclaims back on Bryant Street. It’s why he delights in offering first-time visitors these conversion moments—a revelatory taste that melts elegantly on the tongue.