Words by Loureen Murphy

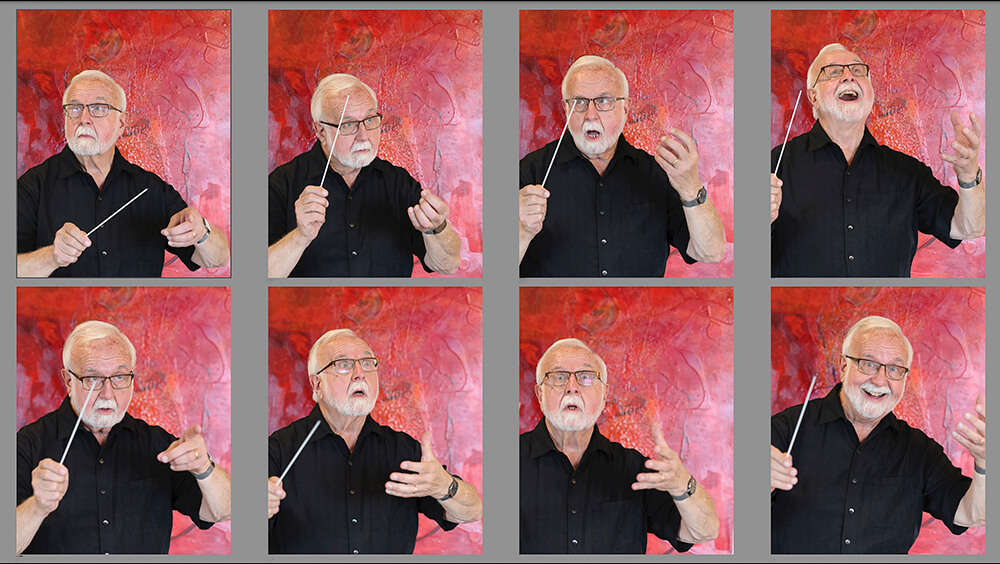

A wave of Mitchell Sardou Klein’s magic wand unleashes dynamic tales, resonating with power and delicacy, exultation and depth. Unlike apprentice Mickey Mouse in Fantasia, the maestro of Peninsula Symphony Orchestra remains in complete control of his baton’s wizardry. Now celebrating 40 years at its podium, he shares the elements of his orchestral alchemy with bass player Jeff Wachtel harmonizing. Both men were reared in New York, trained under noted musicians and ended up in the Bay Area, making music with the Peninsula Symphony.

Surrounded by Music

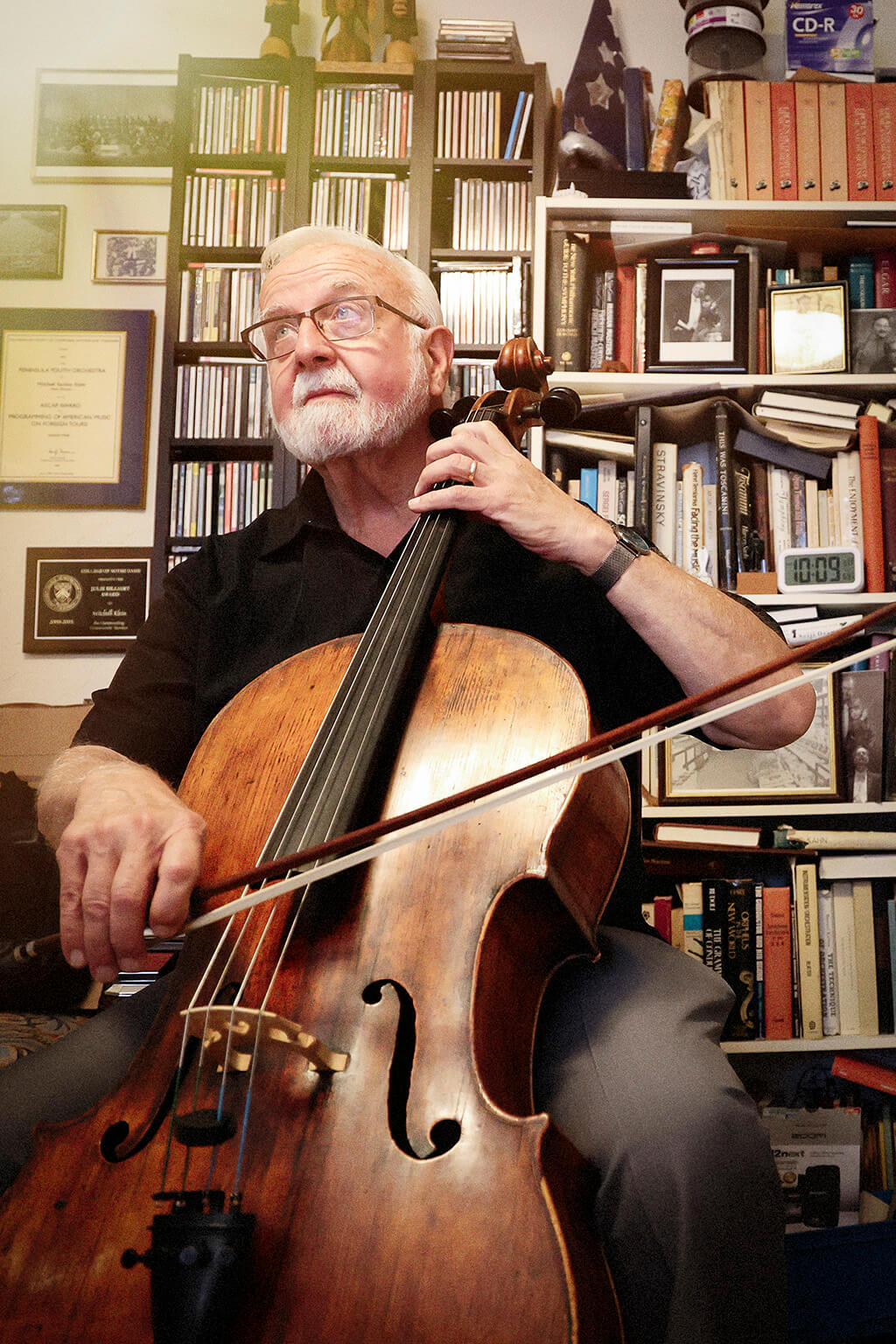

Mitch grew up free of a sense of musical destiny, even though his cellist father co-founded the Claremont Quartet, and his mother was an accomplished pianist and ballet dancer. In placing a half-size cello in his four-year-old son’s hands, Irving Klein simply drew Mitch into the family milieu. Though the close connection to his dad brought him joy, the self-described nerdy 1950s kid preferred a bat and glove to a bow and strings. “Music came pretty naturally for me,” he recalls. “But I wasn’t one of those kids to practice three or four hours a day. That was just not me.”

However, young Mitch did listen to string quartets day and night as his dad’s quartet rehearsed downstairs in their New York home, while his uncle, a Budapest Quartet member, lived and rehearsed upstairs. “I got to see at a very high level, at a very young age, how a musical piece is put together by the composer and by the musicians.” Mitch calls this the “backbone” of his future career.

Still, performing as a professional cellist by his early 20s was not a dream come true. Drawn toward science, Mitch began university as a theoretical physics major and ended up majoring in political philosophy. Finding the career possibilities in those fields unappealing, he concluded, “It was going to have to be music.” Completing a music minor, Mitch then pushed on through grad school, refocused.

“It took me a long time to realize how much music was embedded in me,” Mitch observes. Daunted by assuming the same occupation in which his family had been prominent and successful, “I shied away from it for a very long time.”

He leveraged his cello mastery to take assistant conductor roles in small orchestras. Mitch explains that learning to conduct differs from honing his craft as a musician, in which practice is the key. “That doesn’t work as a conductor until you get up on the podium in front of an orchestra and fail into success, figuring out what works and what doesn’t.”

On taking up the baton, Mitch’s skill and passion for conducting only magnified, as did his reputation. Bass player Jeff, who initially met Mitch at a guest conductor gig at the Stanford Symphony Orchestra, says his impressions have not altered since first downbeat. “I played under many conductors, and Mitch stands above all the others.” Why? His deep passion for the music, extraordinary knowledge of it and the ability to command and impart immediate respect, Jeff attests.

Cover Photo and Above Photo: Courtesy of Annie Barnett

Keeping Score

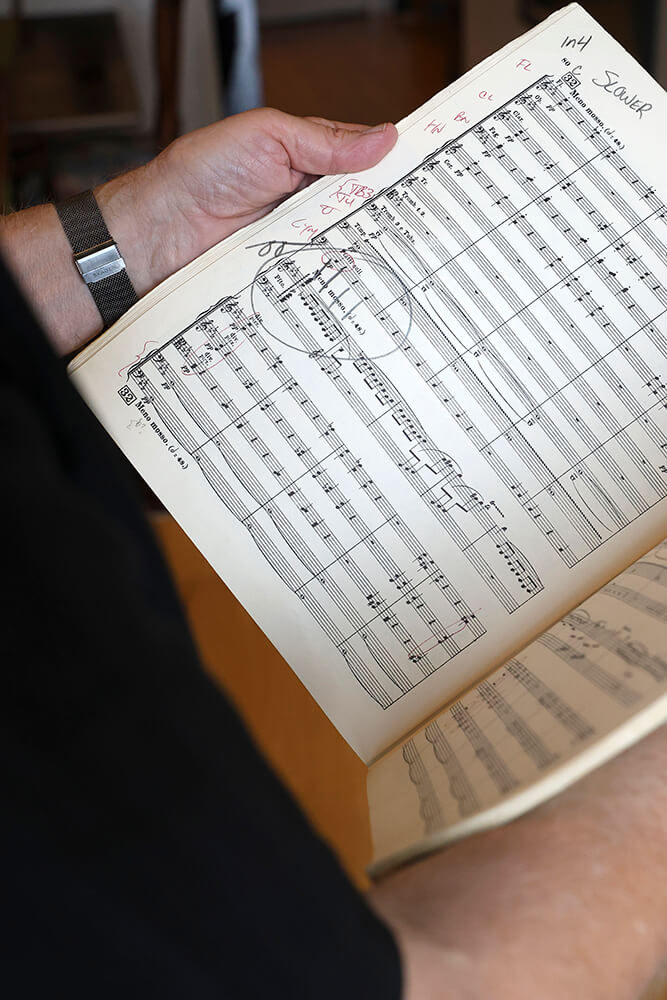

A conductor’s score, with perhaps 20 staves read simultaneously, can boggle a musician’s mind. Mere brain food for Mitch. “Score study is primary because I can read it and pretty much hear the music,” he says. Scrutinizing the score raises questions. Equipped with answers, Mitch comes to the first rehearsal and every succeeding one with clarity on how to shape the piece and ensure all the players work in unity.

In a sense, he’s translating the composer’s emotional language to convey the story. Mitch notes, “Music is about artists telling something about themselves, about the composer, about life, about all the challenges and joys that we experience, to an audience.” Mitch draws the emotions from the composition as he sees them, uniting the composer, conductor and artist in three-part harmony.

With its unique manner of storytelling, “orchestras have this vast palette of colors and shapes and power that no other musical ensemble has had in the history of music,” says Mitch. Jeff affirms that performers delight in “being in the middle of all this incredible sound.”

Mitch’s amazing consistency in score interpretation elicits great trust. Jeff recalls Peninsula Symphony rehearsing a piece that, on first run-through, sounded discordant, as if they’d played the wrong notes. When Mitch asked all sections but one to play more softly, “All of a sudden, what sounded like chaos made perfect sense. It all came together,” says Jeff, adding, “He can deconstruct the most difficult passages.”

Photo: Courtesy of Jim Fung - PSO

The Secret Language

People often ask whether the conductor is really necessary. “Aren’t the musicians just looking at their music anyway?”

“It’s an exercise in nonverbal communication,” explains the maestro. “Not entirely, because at rehearsals, we talk. But the less you talk, the more efficient the rehearsal.” They develop a shared nonverbal language, a visual shorthand that is partly learned, partly intuitive.

Mitch honors those who understand that language, perceiving its layers and nuances. He also possesses an immediate way of commanding respect without harshness. “He’s deeply respectful of the musicians,” Jeff explains. In rehearsals, Mitch will compliment a soloist or section when they’re doing particularly well.

With years of conducting experience worldwide, Mitch gets instant deference wherever he directs. When jazz pianists David Benoit and Grammy-winner Taylor Eigsti came to perform with Peninsula Symphony, the musicians felt nervous, Jeff admits. “With the guest artists, we usually get two rehearsals, so we really need to be on top of things.” When Mitch came out, he had complete command and genuine relationships with the musicians, whom most had only seen on album covers. “He put everybody at ease, right from the start,” Jeff says.

Up the Scale

Almost from his start with Peninsula Symphony, Mitch has been instrumental as the director of the Irving M. Klein International String Competition in San Francisco, watching many winners go on to vibrant musical careers.

Then in 1997, Mitch co-founded the Peninsula Youth Orchestra with Sara Salsbury, and directed its Senior Orchestra for 27 years, taking teens on international tours every two years before retiring and handing off the baton this year to Brad Hogarth. The best part of his experience leading the talented youngsters? “Seeing the orchestra come away with the pride of doing their best playing in front of a European audience,” Mitch responds. These young musicians learn to contextualize music history while exploring the composers’ hometowns.

Photo: Courtesy of Annie Barnett

New Notes

Venerable reams of symphonic music could supply the symphony for the foreseeable future, yet Mitch relishes introducing artists to new composers and fresh pieces. “If you’re doing a world premiere, you really have to look so deeply into the composer’s intentions,” he describes. “Everything you do is new.” The risk? “You don’t really know until you do it how well it communicates with the audience.” For musicians like Jeff, the risk pays off in exposing the music community to works they haven’t heard before.

With variations on that theme, Peninsula Symphony’s 76th season kicked off with some original orchestrations by Menlo Park’s own Taylor Eigsti, along with Gershwin’s iconic Rhapsody in Blue. There’s also November’s annual performance with the Stanford Symphonic Chorus. “It’s always a treat,” Mitch says. The season finale will feature the 2023 Klein Competition Winner, violist Emad Zolfaghari, in Respighi’s stunning The Pines of Rome in May 2025.

The long-term synergy between maestro Mitch and his musicians—some of whom predate his time with PSO—has created its own living instrument: the orchestra itself. “What’s unusual about Peninsula Symphony is that it’s really community-based, community-connected,” he describes. “They bring a huge amount of energy and dedication to what they do. Everybody’s there just to share the joy of making music together.”

Seven Questions with Maestro Klein Family life? Married to Patti 40-plus years, after meeting in an orchestra. We have two energetic grandsons. Instruments played? Cello and piano Time with Peninsula Symphony? 40 years Favorite concert venue? Dvořák Hall in Prague Career crescendo? Our first Peninsula Symphony concerts in October 2021 after the very difficult Covid year. Getting the orchestra together and performing for our wonderful audience was very renewing and exhilarating. Crunchy or creamy? Definitely crunchy. Crunchy as a generalization in life is much nicer than creamy. Skateboarding? Never tried skateboarding. I try to do a lot of walking and hiking, especially in places like Point Reyes, the San Mateo County coast and the East Bay Parks.