words by Silas Valentino

Before taking his first sip, the spy novelist praised the barista.

Barry Eisler arrived by bicycle with a helmet full of hair and ordered a small coffee from Saint Frank, a bijou café he had just discovered near the train tracks in his adopted town of Menlo Park. He cheerfully commended the staff for the pleasant set-up and then paused to soak in the scene.

When you’re a creator of worlds (or a career novelist), every new arena is subject to being fodder for an unwritten plot.

When he’s writing about a specific location in our shared world—bars, restaurants, judo and jiu-jitsu training academies, streets and alleys—Barry insists on precision for these scenes, often snapping pictures of the European door handles and checkered bathroom tiles that grip his attention to later ensure accuracy while writing.

If mistakes occur even after exhaustive scrutiny, there’s a perennial page on his website updated with mindful corrections and annotations, where he’s rectified errors like inaccurately-described refrigerators in a Trader Joe’s beer aisle or the precise suffering that an exsanguinating chest entails.

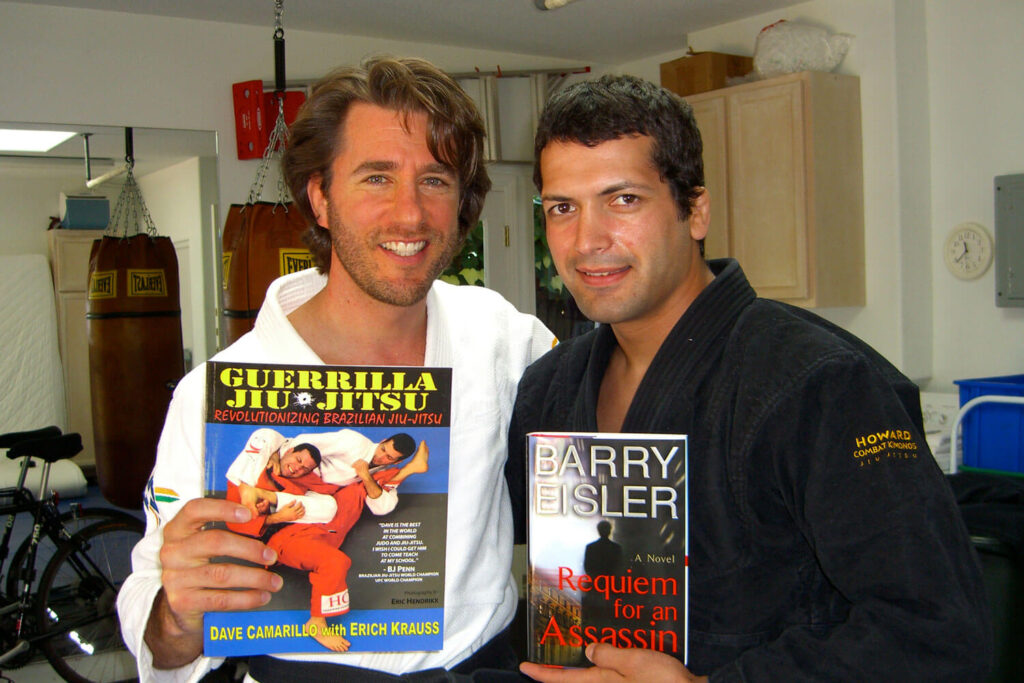

Such a meticulous process produces novels weighty with detail; so much so that The New York Times describes Barry’s fastidious prose as “kind of nerdy” in a glowing review of his 2016 novel Livia Lone. His principal character is the anti-hero John Rain, who has appeared in 11 espionage novels and counting, as the assassin for hire who operates by his own personal code. The series has garnered praise from Keanu Reeves and Elizabeth Warren for its immersive mystery adventure with comprehensive hand-to-hand sequences in martial arts.

The books are also damn fun to read. Barry objectively composes stories using a particular writer’s commandment; quoting T. S. Eliot, Barry explains how “the giving famishes the craving” or how he grounds readers in his world by prudently revealing information for each who, what, when, where and why.

“This is what I need to ground you in the story,” he explains. “I have to nourish you with something every sentence. Every piece of information is used to seduce you out of your daily life and into the story—how am I going to get you to pay attention? I famish to make you hungry for more.”

While writing his first book during the 1990s, Rain Fall (later retitled A Clean Kill in Tokyo), Barry and his wife of 30 years, Laura Rennert, a literary agent and fellow author, were living as expats in the Japanese capital.

He was well underway with a storied career, graduating from Cornell Law School in 1989, spending three years in a covert position with the CIA’s Directorate of Operations before becoming a lawyer specializing in technology for an international law firm.

But Barry was tacitly saturating in interests he describes as dry kindling awaiting a spark. From reading arcane research like the puckish body disposal book Be Your Own Undertaker or hearing the Japanese pianist Junko Onishi perform at the Club Alfie to earning his black belt at the Kodokan Judo Institute in Tokyo, Barry simmered in his curiosities.

His fire to write ignited one night on the subway platform at Ōtemachi Station. An image flashed before his mind of two men trailing someone down an alley. He started asking himself questions—Why are they following him?—before forming answers: It’s because they’re assassins. Well, he thought, then who hired them?

Each question and answer framed the next, nourishing a story with an appetite and a bite.

“Every answer you get, you subject to those questions. Then it turns out there’s a mirror image phenomenon. When I teach a class on openings, the best example I’ve come across is The Key to Rebecca,” Barry says, of the Ken Follett bestseller.

“It begins with: ‘The last camel collapsed at noon.’ It’s not everything because if I give you everything, you’re not famished. That sentence suggests that it’s probably a desert. Sand dunes. Okay, I’m starting to see it. What’s it about? Well, tell me this: Is what’s happening good or bad? The word ‘last’—it sounds bad. This guy is in trouble. Think of all the things you’re beginning to realize. My question now is, ‘Who is this guy?’ There’s a lot of craft in the balance between telling you and nourishing without telling too much.”

Barry is a natural teacher, both for himself and with students. He’s taught classes on technology licensing at Santa Clara University School of Law and often instructs writers in courses or at seminars. Sometimes he can’t help himself from pausing a movie he’s watching with his daughter to point out a storytelling technique.

Teaching is as sacred as anything for Barry and he recalls a moment of clarity while training at the Kodokan Judo Institute in Tokyo. He was struggling to nail the triangle chokehold when a senior student came over and swiftly repositioned Barry’s left arm from the side to the back of his opponent’s neck. It was a three-inch difference to complete the move that took only seconds to learn but left Barry struck.

“I remember walking home from training that night thinking about this guy,” he says. “He had trained for over a half-century and then came over to me to impart some wisdom for free that had taken him all that time to learn.”

Barry stops short of calling himself autodidactic because he says it’s too broad of a term, but he admits an adept ability to be his own teacher. While wrestling in high school in Milbourn, New Jersey, Barry read whatever he could find to enhance his ability on the mats.

During his undergrad years at Cornell, Barry’s blend of interests for geopolitics, martial arts, escape intervention and forbidden knowledge led him to apply to the CIA. One of the tests was a geopolitical and history exam and to prepare, he would bounce an inflatable globe while lying on his bed to constantly quiz himself on Botswana, Paraguay and every corner of the world. He left his exam feeling confident but second-guessed himself on who was the then prime minister of Australia.

“When I got back to my apartment,” he says, “I called the Australian embassy to ask who their prime minister was and the voice on the other end in a thick accent said, ‘It’s Bob Hawke, mate!’”

Barry scored a 50 out of 50.

His experience in the CIA suggests an insider’s perspective for his novels of espionage with characters working for government agencies, but Barry is quick to brush that aside, often joking that the CIA is a malfunctioning bureaucracy or “a post office with spies.” He’s more interested in the facts that lie in bare view.

“Most of what’s secret about the CIA is already available,” he reasons. “How do I know the CIA is intent on influencing and infiltrating the mainstream media? John Brennan, the former director, is an analyst on MSNBC. Half the staff on cable news are retired CIA.”

Since publishing his first book in 2003, Barry has released a new title nearly every year. His John Rain series, and the more recent series centered on the heroine Livia Lone, are released to international fanfare. A bar in Osaka, Japan, that Barry wrote about in his first book, often receives mail from readers looking to connect with the author.

“What’s nice about getting older is that I’m not jealous of other people. There are writers who are galactically better than me,” he says, before breaking into a smile, “but no one else can write these stories. And if I wasn’t born, these stories never would have happened