Words by Sheri Baer

Allyson Hobbs distinctly remembers the first time she saw Stanford University. After flying out from Chicago for a final interview in January 2008, she was chatting with a faculty member as they arrived on campus. “We were talking about Ohio State football and we turned down Palm Drive,” she recalls. “All of a sudden, my breath was taken away. I couldn’t believe the beauty of it. I thought to myself, ‘Wow! I desperately want to teach here.’”

Allyson secured the position and made the move. Now an associate professor of American History, she is also director of Stanford’s African and African American Studies program (AAAS), which is marking its 50th anniversary this year. Founded in 1969, AAAS was Stanford’s first ethnic studies program and the first of its kind at a private academic institution. “Many programs are having their 50th anniversary around this time,” Allyson notes, adding that it’s no coincidence. “These programs were created in response to student protests in the aftermath of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.”

Originally from Morristown, New Jersey, Allyson says that she was raised in a very supportive community. “My parents really shielded me and gave me an idyllic childhood,” she says. “They always talked about how lucky we were to live in that kind of environment.” Allyson attended Harvard in the mid-’90s, where she was exposed to a broader perspective. “There was a robust conversation about race at that time in college, and I think that really ignited my interest.”

However, Allyson graduated without a clear vision of what she wanted to do. “I loved history but I certainly had no understanding of it as a career path,” she reflects. She initially tried investment banking and then advertising: “That didn’t feel like my passion and I started looking at the books on my bookshelves and realized how much I loved history.”

That insight led her to pursue masters and PhD degrees in U.S. History at the University of Chicago and took her to a city that redefined her way of thinking. “Being in Chicago, there were so many issues around race relations, income inequality, unfair housing policies and gentrification,” she says. “All of these issues that I hadn’t been exposed to became part of my everyday. It was a real world learning experience.”

Relocating to Chicago also connected Allyson with her extended family. Although her parents had moved to New Jersey where she was raised, she had aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents living in Chicago. “That’s what made me really excited and passionate about African American history. I started to realize that my family is an American history story—from my ancestors in the South and then later generations coming to the North as part of the Great Migration and then congregating on the South Side of Chicago. All of a sudden, history became really personal to me,” she says.

Allyson especially appreciated the rich storytelling of her aunt, who served as the family historian. When Allyson came home fascinated by a story about racial passing, her aunt recounted the experiences of a distant cousin who had grown up on Chicago’s South Side in the ’30s and ’40s. According to her aunt, this cousin was very light-skinned and when she graduated from high school, her mother encouraged her to move to Los Angeles and pass as a white woman. “Her mother was insistent and believed that passing as white would give her daughter a better life,” Allyson was told.

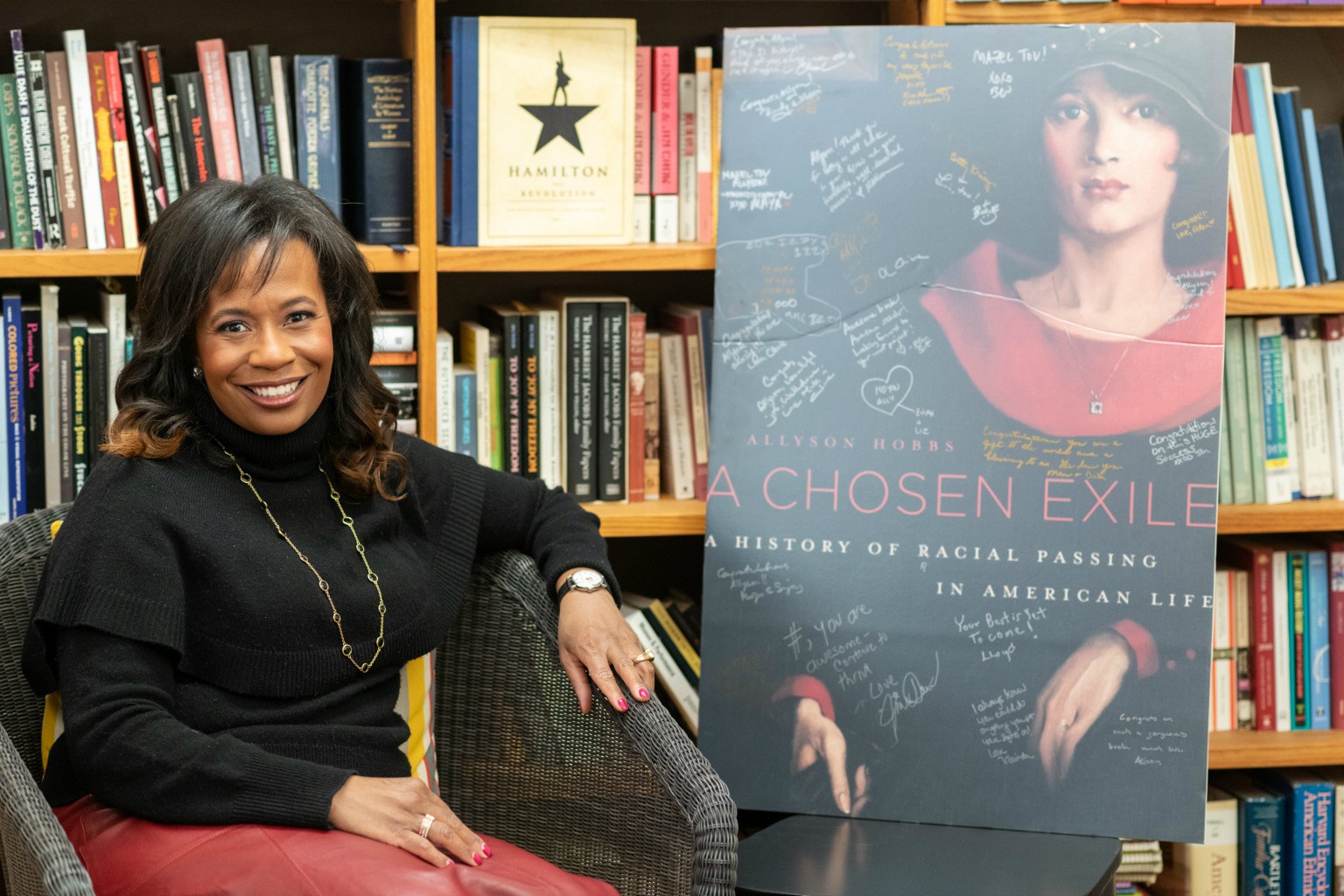

That story inspired Allyson to write her first book, A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life, tracing the practice back to the late 18th century. “People who passed were able to access better jobs and live in better neighborhoods, but I wanted to uncover what it really meant to the people who walked away, what they had to give up,” Allyson says. “Writing the history of passing is really writing the history of loss.”

Allyson is three years into working on her second book, Far from Sanctuary: African American Travel in 20th-Century America, also based on family stories: “My second book is about what the “open road” looks like through the eyes of black travelers. We have so much mythology about just getting on the road and the spontaneity of driving, but that was not the case for African Americans.”

Thanks to the recent box office hit Green Book, the topic is experiencing an added surge of curiosity. Written by a black postal worker named Victor H. Green, the travel guide was originally titled The Negro Motorist Green Book. For her research, Allyson attempted to retrace her family’s Great Migration route from New Orleans to Chicago, including a stop in Memphis. “One thing that’s really interesting is that the Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King was assassinated was listed as a stop in the Green Book. It was a black-owned hotel and King stayed there several times,” Allyson relates.

Allyson’s writing extends beyond her books. She regularly contributes to The New Yorker and her work has appeared in publications including The New York Times, The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post and The Guardian. “Sometimes there’s something in the news that just shakes me or bothers me deeply and I’ll feel that I want to take action,” she says. “A lot of my writing stems from a desire to do something—to make even a small contribution.”

Although Allyson’s plate is full with writing and research, her students are clearly her priority. She teaches courses like “20th-Century History” and “African American Women’s Lives” but also delves into non-traditional subjects ranging from the cultural phenomenon of Hamilton to Michelle Obama. “We can tell the whole history of African American life through her,” Allyson says of America’s former first lady. “From her enslaved ancestry to her family taking part in the Great Migration to her experiences at Princeton, which also tells the story of first-generation students in college.”

Allyson is gratified by the growing interest in African American studies—and that Stanford’s program is attracting students from all backgrounds eager to understand more about African American history and unfolding current events. “I think students are hungry for this history and taking comfort in it too, in knowing that there are cycles in history,” she says. “Obviously we are living in an unprecedented moment, but other people, other generations, have also lived in unprecedented moments.”

It’s been 11 years since Allyson caught her first glimpse of Stanford’s Palm Drive and iconic grass oval. Her office reflects the passage of time, from tightly packed bookshelves to countless pieces of memorabilia—Allyson’s author caricature from The New Yorker, an oversized poster of her book cover signed by friends, a photograph of Allyson with her students at the 2016 Women’s March in Washington D.C. While Allyson misses her family in the East, she fully embraces the Peninsula’s warmer weather and unique spirit: “I love the energy and vibrancy here. There are so many opportunities and a feeling that anything is possible.”