Words by Johanna Harlow

To Dan Lythcott-Haims, time is an artist.

After rediscovering photography in his late 40s, Dan began capturing shots of corrosion around scrapyards, forklift and heavy machinery rentals and auto salvage yards. “With the camera, I started to see the art in the world—and what I saw was the textures and colors and patterns and forms of decay,” shares the Palo Alto resident. “It sort of spoke to me as the art that nature and time have created.”

Dan appreciates that when elements interact on the microscopic level, they are capable of creating something exceptional on a larger scale. Rust deserves recognition because something miraculous happens when atoms on a piece of iron combine with water and oxygen to create something… more. “It’s grown into something kind of random and beautiful,” he marvels.

Similar to the transformation of a bronze patina, Dan has also developed with age. One of his big milestones was moving to his first studio at Art Bias (known as The Art Center of Redwood City back then)—because it meant recognizing himself as a professional artist. As the former creative director of Pandora’s design department, Dan’s mind has always been innovative, and yet… “I was always creative; I came from an artistic family, but I didn’t feel like I had whatever artists had,” he reflects about his early insecurities. Moving to a studio also meant invaluable mentorship opportunities. “I think my professionalism increased quite a bit while I was there. I was able to really talk to people about some of the business aspects of being an artist and selling art.”

Dan’s current studio resides at The Alameda Artworks in San Jose, and his work can be found at open studio events, exhibits and online. Previous solo shows include Schultz Cultural Arts Hall, Pacific Art League and the International Art Museum of America. In addition to being held in private collections, his creations grace the walls of local cafes.

It was through exploration at his first studio that Dan began branching out to three-dimensional art. After many photoshoot outings, he’d collected quite the assortment of bric-a-brac ranging from chains and barbed wire to washers and saw blades. “I had to do something with them,” he says. “I couldn’t just leave them. I wanted the work to come off of the flat plane of the photograph. I wanted to display them somehow.”

Soon, he started mounting his rusted gems on maple wood frames, “almost like I was presenting a jeweled object to the world,” describes Dan. “I would take a rusty nail or a rusted piece of metal and make it special by the way I was presenting it.” He allowed his pieces to evolve by intentionally leaving the wood unfinished, the color of the rust transferring to the frames over time. “Everything ages,” he observes.

One man’s trash truly is another man’s treasure—and over the years, Dan has found a gold mine in places like Alan Steel & Supply Co, a Redwood City supplier bountiful with pipes, i-beams, rolls of wire, gears and casters. “You can buy stuff by the pound, which is fun,” he grins.

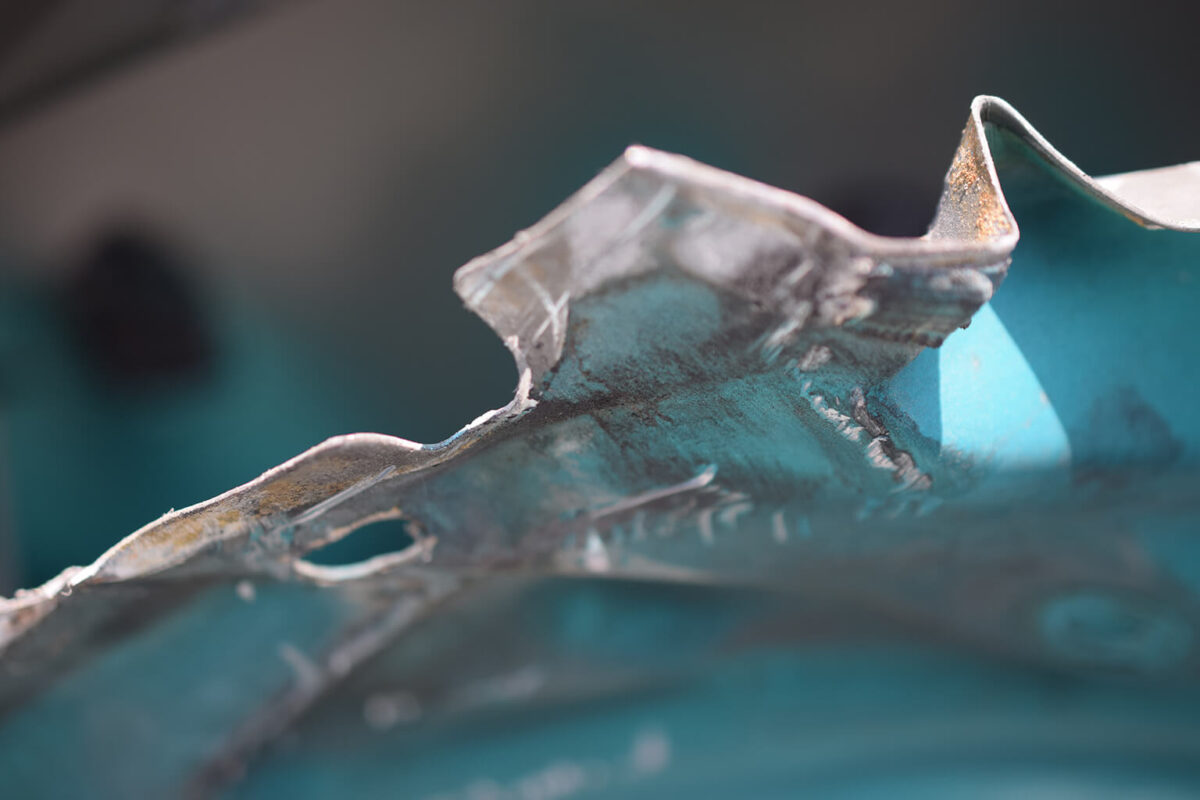

One project of note is Dan’s Alchemy series. By weaving wire through perforations, he fashioned a kind of metallic textile. As he experimented with different kinds of wires and thicknesses to find the right look, Dan found a therapeutic trial and error element to the project. Old materials were too brittle for assemblage, so he found a copper wire that met his needs, then oxidized it with a vinegar spray, leaving it to soak for different lengths of time to create varied textures and shades of green. “Every piece is unique, even though the chemical reaction is the same,” he notes. “Technically, as my scientist mother-in-law would tell me, it isn’t alchemy, it’s chemistry. But the change that comes over the metals to me is magical.”

The Alchemy series was Dan’s first time using new materials. “I felt a little bit uncomfortable sort of ‘faking’ the rust, but I have met some artists and that’s what they do. They patina metal in different ways with different chemicals. So I realized it’s not fake—it’s just a different process.”

Despite all these assemblage and sculpture projects, Dan still makes time for photography. Like his Collections series, which features objects from flea markets around the Bay Area. “One of the things that I like about repetition—when I take similar or identical objects and repeat them—is that overall, there’s this emergent, organic quality.” He compares it to the ocean. “Every coral reef is unique, even though each polyp is identical.”

One of Dan’s favorite projects to date is a series of cages and keys from 2020—the largest of which holds 400 or so keys and stands at almost human-height. “I love the scale, the scope,” he says with a smile. “And it has some unexpected characteristics. It makes a beautiful noise when it’s bumped, all the little keys tinkling against each other. The visual of all the movement is wonderful and unexpected.”

Many have told Dan that the project has spoken to their feelings of isolation during the shelter-in-place. “Each viewer can find in it what they want to find in it,” he invites. But as for him… “The meaning is in the making,” says the guy who finds wonder in the junkyard.