Words by Sheryl Nonnenberg

The Marie Kondo method of house decluttering calls for discarding things that no longer spark joy. When it comes to Evelyn McMillan’s extensive collection of textiles, that mindset of paring down clearly doesn’t apply. A visit to her mid-Peninsula home reveals copious treasures stored in closets, wardrobes and chests—and Evelyn is eager to share the history and importance of each and every mola, batik, embroidered cloth and piece of lace she has acquired over the course of her lifetime.

It all began, she explains, with her mother’s penchant for embroidering small flowers on the collars of her dresses. Her mother and aunts did needlework and, at the age of five, Evelyn also began to learn the skill. But the collecting bug took hold when she started going to rummage sales organized by her mother. Evelyn loved helping the women sort and arrange clothing, and for her efforts, she was allowed to select a small item. “I bypassed the toys and books and went straight to the small pieces of lace and embroidery,” she laughs. You could say that was the first stitch in Evelyn’s lifelong obsession with the needle arts.

“Lace and embroidery don’t have a reason to exist,” she explains. “They don’t keep you warm or dry. It is the human love of color, pattern and creating beauty. What can you make out of a needle and thread?”

Fast-forward to the 1980s when Evelyn, a career librarian at Stanford University, began to attend the annual craft fairs on campus. It was here that she became aware of the colorful and detailed textiles of the Hmong culture. “I was blown away by the skill and needlework of the pieces I saw and knew they might be a dying art,” she recounts.

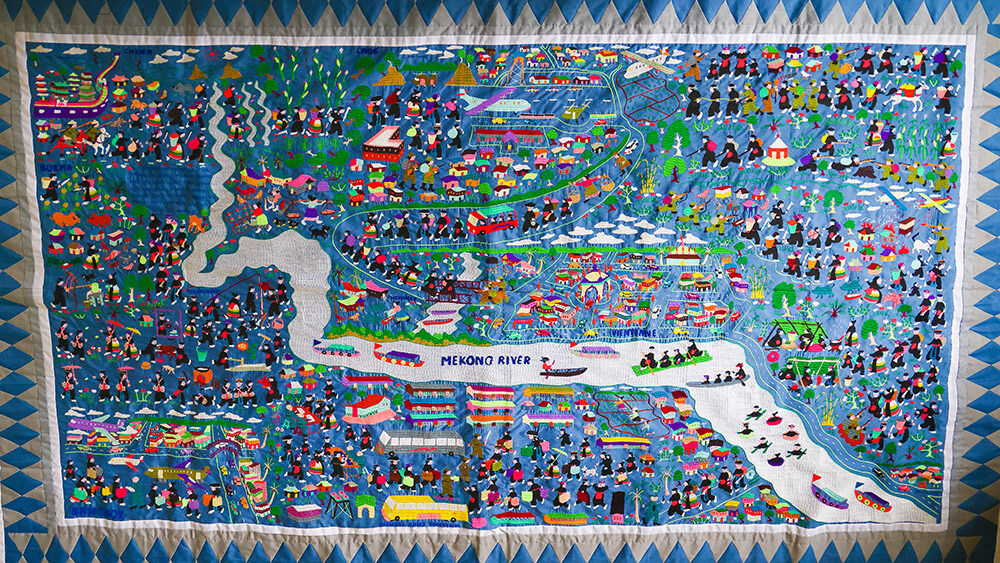

Evelyn became friendly with the women who were selling their work and learned of the turbulent history of the Hmong people, which was often portrayed in the form of story cloths. These large, colorful cloths consist of hundreds of figures and symbols that tell the migration story of the Hmong from China, through Laos and Vietnam, finally ending in resettlement in places like California’s Central Valley as well as in Minnesota and South Carolina. “The Hmong had no written language until the 1950s,” notes Evelyn. “This was how they told their story.”

As an example, she gestures to an incredibly detailed piece with tiny figures performing traditional dances, taking part in ritual customs and, sadly, being pursued by figures with guns as they made their way to refugee camps. Evelyn owns 49 of these story cloths. “I hope I am helping to preserve these,” she says, “as well as helping the women to pay the rent. They knew that I appreciated their work.”

Another of Evelyn’s prized collections is lace, specifically lace made during World War I. In the 1990s, she began spotting beautiful handmade lace tablecloths in second-hand and antique stores. An exhibit at the Hoover Tower on campus really honed her interest in “war lace” and the fascinating story behind this time period. Prior to 1914, lacemaking was a national art in Belgium. Created mainly by women, it was a thriving industry with exports to countries worldwide. With the onset of the war, the sea blockade of Belgium not only deprived people of necessities like food but also the thread needed for lacemaking.

Herbert Hoover, who was living in London at the time, intervened, and through the Commission for Relief in Belgium, arranged for famine relief and also the importation of lace thread. Evelyn shares that the lace industry, which included 50,000 workers, survived the war thanks to his efforts. In gratitude, commemorative gifts in the form of tablecloths were sent to his wife, Lou Henry Hoover, and are now on display in the Hoover Library and Archives.

Thanks to her extensive research, Evelyn can discern the difference between handmade and machine lace—even by just looking at a photo. She has amassed hundreds of examples, some in the form of tablecloths, pillowcases and other utilitarian formats but also small squares that have been cut away from larger pieces. This knowledge has enabled her to identify the many symbols found in pictorial lace that express outrage and sadness about the war. Animal figures portray the Allied countries and some lacemakers even depicted the Belgian lion defeating the German eagle—a subversive expression that could have had dire consequences.

World War I Belgian Lace Lacemakers often used real or mythological animals as symbols in their work. In this tablecloth, Belgium: Lion, Russia: Bear, Great Britain: Unicorn, France: Cockerel, Italy: Standing Lion, Serbia: Eagle. (The United States had not yet entered the war.)

As a result of her research and collecting, Evelyn has become an acknowledged expert on the subject of war lace. She has written numerous articles for PieceWork magazine and is cited in an eight-volume publication on world textiles. Her passion for the subject has propelled her into an unexpected post-retirement career: textile consultant. “Opening my emails in the morning is a great adventure,” she reports. “I never know who I am going to hear from.” Evelyn has assisted countless people in determining whether their lace is valuable—and what to do if it is.

Recently, a man from Vermont sent her a photograph of a lace tablecloth he had inherited. Putting her research skills to work, Evelyn discovered the town in Western Flanders where the lace was made (doing this required working in French and Flemish) and even found a photograph of the church depicted in the center of the lace, which had been destroyed by the Germans and then rebuilt. During the course of the year she spent on this project, the owner trusted Evelyn enough to actually send the lace to her for some conservation work. “It was custom-made in the town, with many women working on it,” she divulges. “It is a very complicated, detailed piece.”

Thanks to her hard work, not only has the lace been identified and conserved but it will be returning to the small town of Hooglede in Belgium, where it will be displayed in the City Hall as a memorial

to the war.

Hooglede Tablecloth In this piece, two lacemaking techniques are used: bobbin lace and needle lace. Bobbin Lace is done by weaving (or plaiting) threads together to create patterns. The thread is wound on pairs of wooden bobbins; complex figural lace can require hundreds and hundreds of bobbins. Needle Lace is built up from individual knots or loops done with a needle and a single thread on a skeleton of outline threads that have been established over the pattern. “Beginning lacemakers worked on it as well as expert lacemakers,” Evelyn explains. “I love that about this lace; everybody’s work was included.”

Returning the lace to its origin—and establishing its provenance—was obviously very rewarding for Evelyn. But whether it’s an intricately sewn tablecloth or just a patch of colorful embroidery, it’s clear that every piece in her collection sparks joy in her heart.

“I think they are an underrated art form—underrated because we live surrounded by everyday textiles and because they are mostly made by women,” she observes. “For me, textiles, like art, don’t have to do anything or be anything. Their ability to bring joy, beauty, knowledge and interest into our lives is enough.”