The ship is docked, its passengers disembarked but Captain Jackson Gentry has one last nautical story to share before going ashore. “Come watch this boat burn up,” he warmly invites, pulling up a video on his phone.

Since before he could drive a car, Jackson has driven a boat; he’s captained fishing boats since his teens, leads commercial watercrafts for whale watching on his weekends and for the last 19 years, he’s helmed the blue and white research vessel used by the Marine Science Institute in Redwood City.

He’s had 40 years on the water with zero injuries or disasters, minus that one mayday distress signal he sent out on a chilly May morning in 2016.

He was off the coast of Malibu in Southern California helping a friend who had just purchased a 37-foot power boat called the Allison Rae. They were piloting the ship to Santa Barbara when the engine inexplicably caught fire. Three minutes later, the entire boat was in flames.

Jackson, his friend and his friend’s dog dove into the water and were quickly rescued. No one was hurt (apart from the Allison Rae, which sunk to the ocean floor), and Chief Norman Plott of the Ventura County Fire Department described Jackson as an “experienced mariner” to the local NBC news affiliate.

Looking back today, Jackson credits a former boss for preparing him to survive the unexpected at sea. Coincidentally, both he and his friend had worked for Captain John Sczostak years prior, where they had learned the same emergency procedures—along with critical lessons in resourcefulness and diligence.

“His way of doing things was to never give up. If something broke on the boat, we wouldn’t return to port; we’d sit there until it was fixed,” Jackson says. “Sometimes he’d figure it out in ways that were outside the box. Duct tape, baling wire and toothpaste—we’re ready to go!”

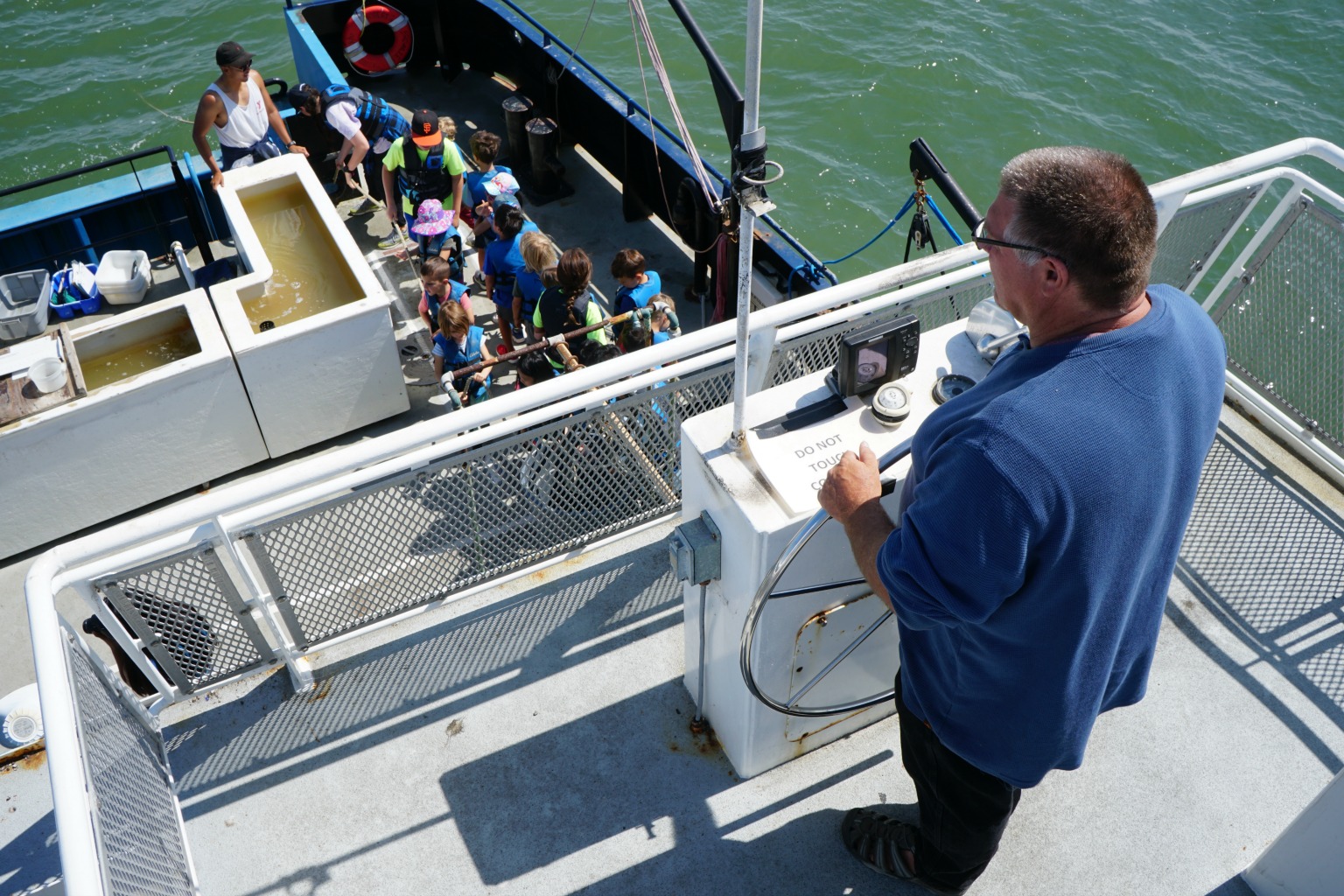

Jackson captains the Institute’s research vessel Robert G. Brownlee, an old-style boat that uses a system of cables to pull the levers in lieu of electricity. The Institute offers a marine science camp during the summer and on a recent balmy Thursday morning, Jackson led over 50 campers on a cruise throughout the lower part of the San Francisco Bay to observe marine life.

The Brownlee is laced with Jackson’s ingenuity. He developed a mini claw used to scoop up sediments and materials off the Bay floor to use in lessons with the Institute, and he’s modified the nets students cast while fishing so that they nab the ideal amount and not an overabundance. For the Institute’s holiday party last year, he fashioned old liferings into a clock and coffee table.

The inside of the Brownlee’s deck is essentially Jackson’s office space. A Harry Connick Jr. CD sits idly in a boombox next to the ship’s wheel and stuffed in a crack nearby are a few plush dolls, including a Scooby Doo toy he fished out of the Bay over 15 years ago. One of his daughters, borrowing from her father’s humor, clipped a shark tag on it in case it ever falls overboard again.

Jackson lives in San Gregorio and when he’s not leading excursions for the Institute four or five days a week, he also runs whale watching boats out of Moss Landing and is a relief captain for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It’s not unusual for Jackson to be out on the water every day of the week. Recently, when a friend asked why he doesn’t take a day off, Jackson’s reasoning was simple: “I have a great white shark swimming directly underneath me right now—what could be better than this?”

A conversation with Jackson may go from discussing the ghost town of Drawbridge, where an abandoned railroad station is located at the southern end of the Bay, before shifting to the aviator and barnstormer Lincoln Beachey, who pioneered aerobatics and set aviation records in the early 1900s. He’s an autodidact who learns through podcasts (Radiolab is a favorite), paperbacks and deep dives on the Internet. Jackson would be a proper companion for a round of bar trivia, as long as the questions aren’t too heavy on sports or pop culture. (He wasn’t too sure who Kanye West is.)

Such an expansive knowledge is even more commendable upon learning that Jackson dropped out of Half Moon Bay High School after his junior year. He was born in Montara in September 1965, which he says makes him a member of Generation X by merely a month. Besides an 11-month period during which his family relocated to the tiny town of Wasco near Bakersfield, Jackson has lived his entire life on the Peninsula.

When he was 13, Jackson lied about his age to work as a deckhand for a fishing company. “I remained 16 years old for three years,” he laughs. He was piloting boats by the time he was 15, before he was driving on the street, and once he started working full-time with fishing boats, he left school without a diploma.

Jackson directs the Brownlee to a spot between the San Mateo and Dumbarton Bridges where a relic from World War I is accessible on low-tide afternoons. The U.S.S. Thompson, a Clemson-class destroyer of the U.S. Navy, is partly sunk in mud flats. It’s the Bay’s very own U.S.S. Arizona, half engulfed in water. The science campers are awed by the sight and Jackson is ready to satisfy their wonderment with facts about the destroyer, like how it was used for bombing practice during World War II.

Working with the Marine Science Institute was a godsend but that doesn’t mean it came easy. In 1999, Jackson was raising his two daughters, aged four and five at the time. He needed a job with a schedule conducive to parenting as a single father.

After spotting the Institute’s ad seeking a captain, he dashed over to drop off his resume. When he didn’t get a call back, he returned with another resume. Still no response. Jackson speculates that he left about 25 resumes over three months before landing an interview. “I was the biggest pain in the ass they’ve ever seen,” he jokes.

The Marine Science Institute proved to be the perfect fit for Jackson—no shortage of challenging projects, plus he could bring his daughters to work with him (that is until they got sick of their 550th shark). “This was a real lifesaver,” he says, double-tapping his fingers on the surface of a blue table on the hull.

It’s an hour past noon and time to return to land. Jackson steers the Brownlee into the mouth of the Redwood Creek next to Bair Island and back to the Institute’s headquarters. Before reaching the dock, Jackson uses a pair of binoculars to point out a half-century-old Fargo truck submerged in the slough. It’s rusty and could have easily been shrouded in the murky marshland if it weren’t for Jackson’s keen eye.

“That truck got on that island somehow,” he says, theorizing that it could have been left behind from a bygone Alaskan fishing company that used to work in the area.

It’s a mystery of the Bay, with a story that’s been lost in the tides, but Jackson’s guess is about as good as it’s going to get.

anchors aweigh

EcoVoyage open to the public

500 Discovery Parkway, Redwood City

Saturday, September 14, 10AM