When Joel Simon was 11 years old, a glass Coca-Cola bottle washed ashore at his feet. “Hecho en México” read the label. This well-traveled bottle had ridden the waves north, up the California coast, and was funneled by the tides to Alamitos Bay in Long Beach.

Joel imagined the marine life that the bottle must have seen along its journey: a pod of bottlenose dolphins gliding effortlessly along the surface, highlighter-orange Garibaldi damselfish patrolling their reef territories and a giant squid amid a nighttime feeding frenzy.

Although the bottle was unable to speak, Joel still found a way to unlock the marine theater. Using some rubber bands, a belt, an old bicycle valve and a rubber hose, 11-year-old Joel fashioned a homemade breathing apparatus out of the bottle. It could only hold enough air for three breaths, but the apparatus gave Joel a newfound liberation underwater.

“Being able to essentially stay underwater with this Coke bottle for about six minutes,” Joel recounts, “I had every bit of thrill that I’m sure the Wright brothers did, even if they’re only 18 feet above and I’m only 18 feet below. This was a real adventure into a new realm for me.”

Joel’s childhood ingenuity and unbridled passion for the aquatic world has carried on into his adult life. The Menlo Park resident has been photographing underwater life for over four decades and managing his snorkeling tour company, Sea for Yourself, for the last 25 years.

He now finds his joy in the familiar, whereas most divers and snorkelers find it in the unexpected. “For the truly attentive and the truly alert,” he says, “all is familiar and all is new.”

Growing up in Long Beach, Joel regularly swam, surfed and sailed in the coastal waters. He remembers diving around the old bridge pilings in Alamitos Bay with his homemade scuba gear, enamored with the barnacles, starfish and anemones enveloping the underwater columns. By age 16, he had upped his equipment and training, becoming a scuba-certified snorkeling camp counselor at the YMCA on Catalina Island while volunteering for various marine biology research projects.

But it was not until the early 1970s that Joel first had the idea to photograph the depths below. Today, waterproof cameras are abundant but back then, underwater photography was specialized and arcane.

So Joel had to pull off another feat of ingenuity: He built his own plexiglass, waterproof camera housing system.

“The thrill of being able to take your own pictures underwater was an amazing extension of the intrigue of that marine environment,” he says.

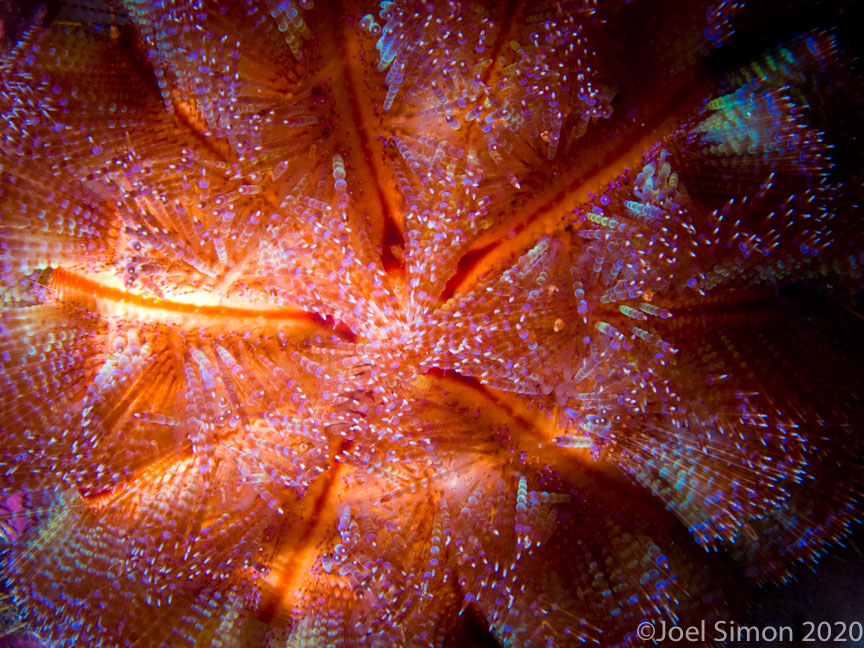

Marine life appears alien to terrestrial-centric human eyes—Joel’s photography style leans into that unfamiliarity. His most captivating photographs are known as macro images: Intense close-ups of patterns or textures of aquatic organisms that blur the line between abstraction and reality.

“For the most part, this is exactly how the camera saw them,” Joel says. “I’m not doing any special Photoshop.”

Joel has three primary tenets for underwater photography. First, he says that people must feel comfortable in the water, adapting to currents, pressure and temperature changes. Second, they should know the limitations of their snorkeling or scuba equipment.

Finally, and for Joel this is the most important, people should learn about the aquatic ecosystems they enter—not only to figure out the best photography opportunities, but also to respect the well-being of the organisms.

“I do firmly believe that snorkeling is one of the most benign ways that people can interact with a wilderness environment,” he says.

Following his father’s advice of “Do what you love and do it well,” Joel searched for a way to turn his love for the sea into a career. After moving to the Bay Area to attend Stanford University, he worked with Peter Voll to establish the Stanford Alumni Association’s Travel Study program. Joel says he was the “pseudo” director of aquatic trips before branching off to start his own snorkeling-specific travel company, Sea for Yourself.

“My goal is to provide an infrastructure that allows people to visit and literally immerse themselves in a wilderness environment in a way that gives them comfort and confidence that might not otherwise be accessible to them,” he says. “That’s really important to me.”

Over the company’s many years of operation, Joel and his colleagues have led educational trips to prominent reef environments such as Fiji, Palau, Bonaire and the Great Barrier Reef. He’s also guided several groups to Tonga to snorkel with humpback whales. Joel says the baby whales behave like puppy dogs, curiously swimming up to the snorkeling group with playful energy.

Joel emphasizes that he wants the trips he leads to be more than just snorkeling—he wants the group to leave enriched with knowledge and respect garnered from the local culture. For instance, he once gifted a local lobster fisherman in Mexico a bottle of rum in exchange for the fisherman’s stories from the sea, passed down from the fisherman’s father and grandfather.

“I always want to be respectful of the environments we visit,” Joel explains. “Whether it’s the terrestrial coastal communities or the marine environments.”

Over his many years of travel, Joel has noticed changes in the communities he visits. With cellular technology now connecting many of these island habitations to the world economy, marine environments that were once resources have become commodities.

But Joel is comfortable with the sea changes. Beyond the local communities, he notices large, year-to-year fluctuations in reef ecosystems. Since the reefs withstood a millennia of extinction events, he’s confident that these environments will persevere past human-induced climate change. Joel says even visiting a reef at different times of the day produces a variance of experiences for the observer.

“You could go to one channel, for example, during what’s called a slack tide when there’s not a lot of water movement and take a look around, but when you come back two hours later and there’s more of a current flying, you’ll have an entirely different experience,” he notes. “The dynamics of the underwater community are oftentimes really contingent, if not dependent, on the tides and the currents. If you had just visited a place one time, you’d never know about that.”

Joel’s perspective and photography of life beneath the waves offer a glimpse into the otherwise unforeseen world. The images stir up intrigue that helps those of us on dry land become further interested and more attentive to marine ecologies.

“When we can talk and communicate both about the strengths and the vulnerabilities of marine environments, those images provide a connective tissue,” Joel says. “And if they can be visually intriguing simply from a point of aesthetics, that’s all the better.