words by Sophia Markoulakis

Hetal Vasavada’s culinary journey—connecting her family’s deep ties to India’s Gujarat region and first-generation Indian-American experiences—began when she was young, savoring her mother’s intricate Indian desserts, yet yearning for the “just add water” boxed American baking mixes of her suburban youth.

The Belmont cookbook author and culinary entrepreneur grew up cooking alongside her mother and ‘aunties’ but it wasn’t until her appearance on Season 6 of MasterChef in 2015 that her career in medical consulting ended and a new path in the culinary realm began.

“I’d never cooked meat before appearing on the show,” Hetal admits. But her vegetarianism didn’t derail her. “There was one challenge where I had to cook a Salisbury steak, and I was looking for a cut called ‘Salisbury…’”

Hetal understood natural pairings—pork and fruit or beef and root vegetables—and had a good knowledge of anatomy, thanks to her science background. “I created a meat matrix,” she laughs about the cooking competition. She ultimately won both meat and non-meat challenges, using Indian ingredients.

That reality-show experience reinforced her belief that food was a happier career choice, and making it to the top six (out of 22 contestants) meant that people were responding to her Indian-American way of approaching her native cuisine.

SPICES

Hetal recommends sourcing spices the way you source fruits and vegetables: knowing the farmer and how they are grown and harvested are important for quality and flavor. She is a big supporter of Oakland’s Diaspora Co. “Sana’s coriander is grown 20 miles from the farm my mom grew up on. It’s lovely to see the farmers she’s helping,” Hetal explains. “Burlap & Barrel is also a great company for ethically sourced spices. Their cinnamon is out-of-this-world good.” There’s a whole industry of female saffron harvesters and processors in Afghanistan, and Rumi Spice employs thousands of women there, providing them with financial security. Rumi’s saffron is Hetal’s favorite.

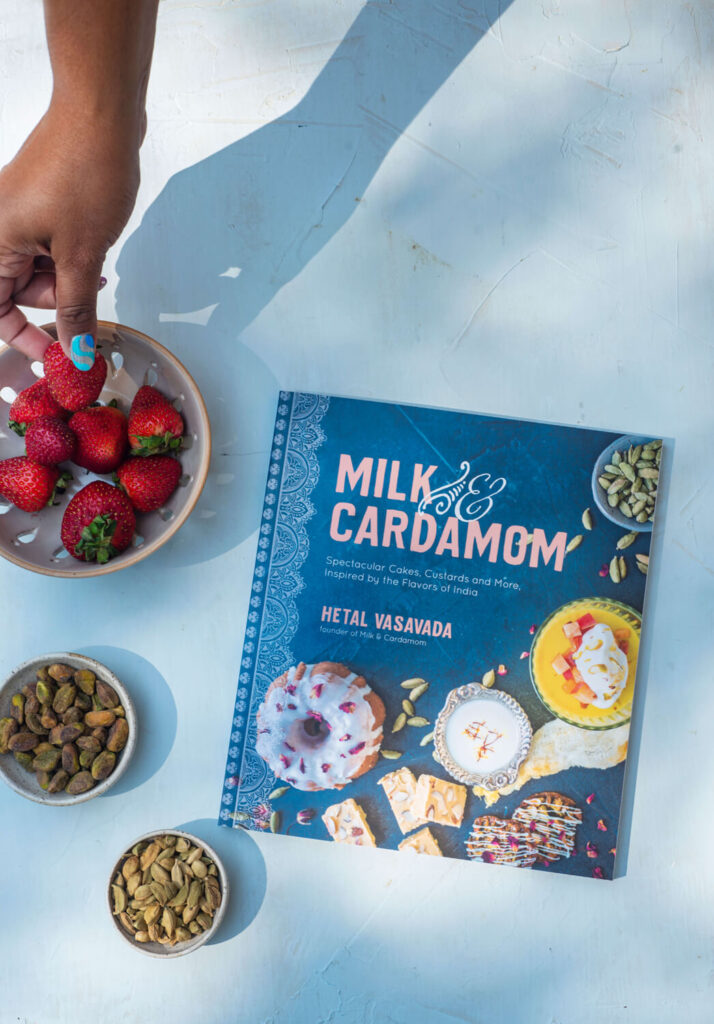

Soon after the show ended, Hetal’s culinary consulting career took off. Her social media, photography and recipe development gigs made it possible for her to recognize the power of social media for her own brand. Indian desserts captured the attention of MasterChef producers, and her proclivity to bridge Indian and American cuisines is what propelled her to notoriety. The culmination was her first cookbook, Milk & Cardamom, published in 2019.

“I started making desserts with the Indian flavors like saffron, green cardamom and rose water that I was nostalgic for and using them with the American desserts that I craved,” she says. “So many of our recipes are passed down orally without exact measurements, and I wanted to recreate them so they could be approachable and reproducible.”

Today, Hetal is building her brand around demystifying Indian sweets and making them accessible to the American palate.

“When I began developing my recipes that marry Indian flavors with more approachable steps, they just blew up,” she recounts. “When my book came out, I learned that there’s a huge representation of Indian-Americans who grew up the same way I did and who were nostalgic for these flavors. A lot of Indian followers, whose spouses are American, appreciated my recipes and recreated them, especially during American holidays, to bridge both cultures.”

Hetal points out that there’s still a lot of work to be done regarding the Anglo acceptance of Asian cuisine. “MasterChef put a lot of emphasis on ‘elevating my cuisine,’” she reflects. “They only said that about the non-American and non-European food that contestants were preparing. Trying to fit my food into the standard American paradigm of protein, starch and vegetable on a plate was very difficult.”

Influential Indian chefs and journalists like Floyd Cardoz and Priya Krishna paved the way for creatives like Hetal to illuminate the diversity of the country’s cuisine. The author emphasizes that there’s more to Indian cuisine than Punjabi tandoori and naan.

“Every state has its own cuisine,” she says, “and people are starting to understand that now.” For instance, Gujaratis make up the largest percentage of Indians outside of India, according to Hetal, but you’ll rarely see soulful, seasonal Gujarati food at restaurants.

RESTAURANTS & SHOPPING

For traditional Punjabi cuisine, Hetal recommends the recently remodeled Saffron Bistro in San Carlos. For a more complex dining experience, she goes to Los Altos’ Aurum. “Chef Manish Tyagi used to be at San Francisco’s (now closed) August 1 Five. He does modern Indian food, and he sources his inspiration from all over India. He’s all about cooking seasonally,” says Hetal. “Literally, the last restaurant I ate at before the state shut down last year was Palo Alto’s Ettan, which serves modern southern Indian food from the Kerala region.” Hetal’s go-to for Indian staples is Namaste Plaza in Belmont for a quick stock up. For a larger haul, she heads to Indian Cash & Carry in Foster City. “They have lots of organic spices and flours that you don’t typically find here on the mid-Peninsula,” she says.

San Francisco’s Besharam, in the Dogpatch neighborhood, is one of very few Gujarati restaurants, and there you’ll find dishes like dahi wada (split lentil dumplings with yogurt and tamarind) and khichdi (a rice and lentil dish). “Heena, the owner, and I are good friends,” Hetal says. “Whenever I go, she does the typical aunty thing and stuffs me silly.”

Hetal is also breaking the dessert social class ceiling. Affluent native Indians buy their sweets; they don’t typically make them. “My mom grew up very poor and my dad grew up as a child laborer cutting diamonds at the age of nine. In our home, everything was homemade. Indian desserts are very difficult to make, and if you don’t have the skill or technique, you’re not going to do it,” she says, acknowledging that her followers (89k and counting…), who might not have grown up watching a mother make mithai (sweets), are willing to give it a try now.

Take burfi for example, which is similar to fudge. “These Indian sweets are made not only by temperature but also by viscosity,” notes Hetal. “You have to feel the sugar to determine when it’s ready.”

Another tactile dessert that is arguably India’s most popular is gulab jamun. These fried balls of dough that are then soaked in an aromatic sweet syrup require skill and plenty of preparation time. The dough’s batter is made from milk solids that the traditionalist would extract from fresh milk simmered over the stove for several hours until all liquid has evaporated. Hetal shares that the flavors of that dessert prompted her to come up with a quicker, more approachable recipe that had a similar, almost toothsome delicate interior, but could still withstand a good soaking of syrup. The recipe for her galub jamun cake appears on her website and in her cookbook. You can also purchase prepared cakes on her website.

“I love watching my followers and customers enjoy these cakes,” she smiles. “They bring people back to a certain joy or memory.”