words by Silas Valentino

In a sprawled display on the kitchen table inside a Belmont home are fragile photographs and dusty journal entries alongside a copy of a faded document with a signed date of 1647. The documents and correspondences are part artifacts, part clues being used to stitch together a multigenerational narrative that would have otherwise been lost if it weren’t for the copious care of a curious couple.

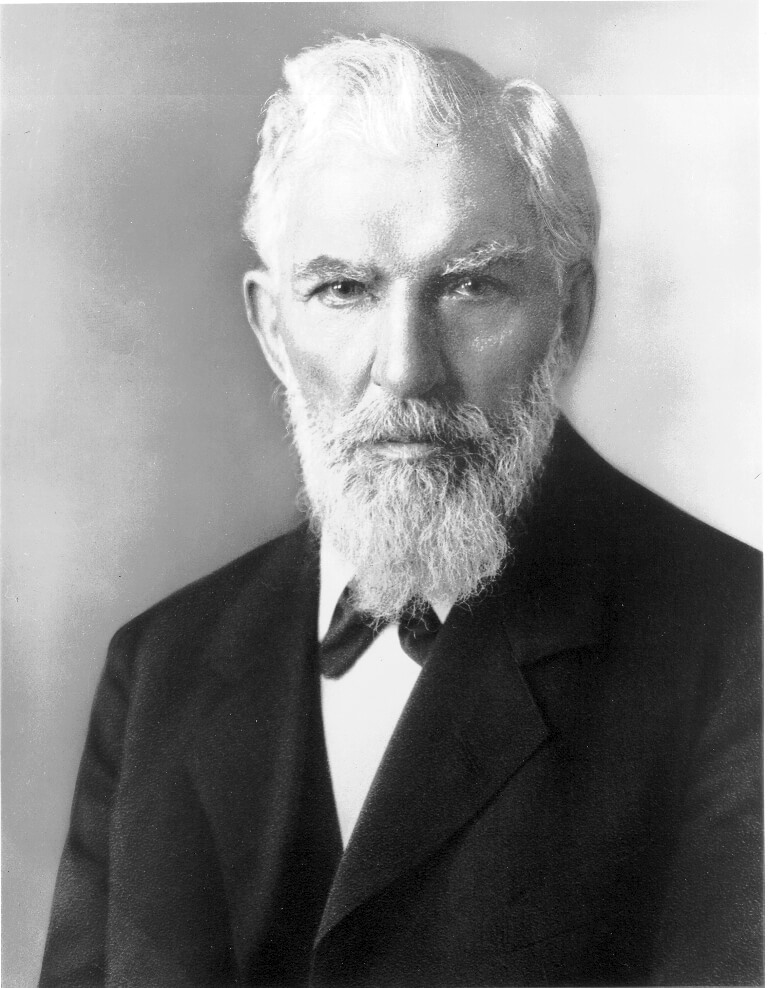

Meticulously piecing together this treasure trove of keepsakes are Ed and Pat Schoenstein. Ed is the grandson of Felix Schoenstein, who established what was to become the most successful pipe organ factory on the West Coast: Schoenstein & Co.

“I’ve rediscovered a man I didn’t know,” Ed says. “I’ve finally gotten to know my great-grandfather.”

Using patience and self-taught archival techniques (not to mention countless German-to-English translations via Google), Ed and Pat have begun to draw a detailed lineage encompassing 13 generations of Schoensteins that spans centuries and continents.

“I’m not an archivist but Ed would come down from the attic with these boxes he inherited and there was always some treasure inside,” Pat says. “This project is like a sticky ball that’s rolling around the house picking up new treasures.”

As the last of nine children, Ed grew up enveloped by stories of his family and the impact they had on bringing music to San Francisco. His father Louis and his uncles installed a massive and electrified pipe organ for the 1915 World’s Fair in San Francisco. His father and mother Josephine spent their honeymoon at the Fair.

One example of family lore that’s been passed down stems from the night they were gearing up for a performance by the famed French composer Camille Saint-Saëns during the closing concert for the Fair in June 1915. The Schoensteins were horrified when a howling noise roared out of the organ because of a technical error, which caused the electronically-operated organ to play at random. The family hustled together to fix the mechanical issue, saving the evening and their reputation.

“It was a curse of modern technology,” jokes Ed, “and a humbling experience for the family.”

In Felix’s diaries, they discovered how he drafted, carved and built the pipe organs while composing the score into the musical cylinders for orchestrions he sold. Orchestrions were a precursor to a jukebox that could reach up to 14 feet tall, and the family sold several of them specifically to saloons in San Francisco. The automatic music players showcased Felix’s breadth of music, cranking out classical songs from Europe as well as folk tunes from America.

“Felix was the Leonardo da Vinci of the family,” Pat says. “He learned English by translating a German book he was familiar with on the history of pipe organs that he rented from the Mechanics’ Institute Library in San Francisco.”

Upon emigrating from Germany to San Francisco in the last quarter of the 19th century, the Schoensteins began by building and selling orchestrions and then transitioned into pipe organs throughout the Bay Area. Their pipe organs championed an American-Romantic tonal style that shot to high demand following the 1906 earthquake and fires as every church and cathedral required a replacement.

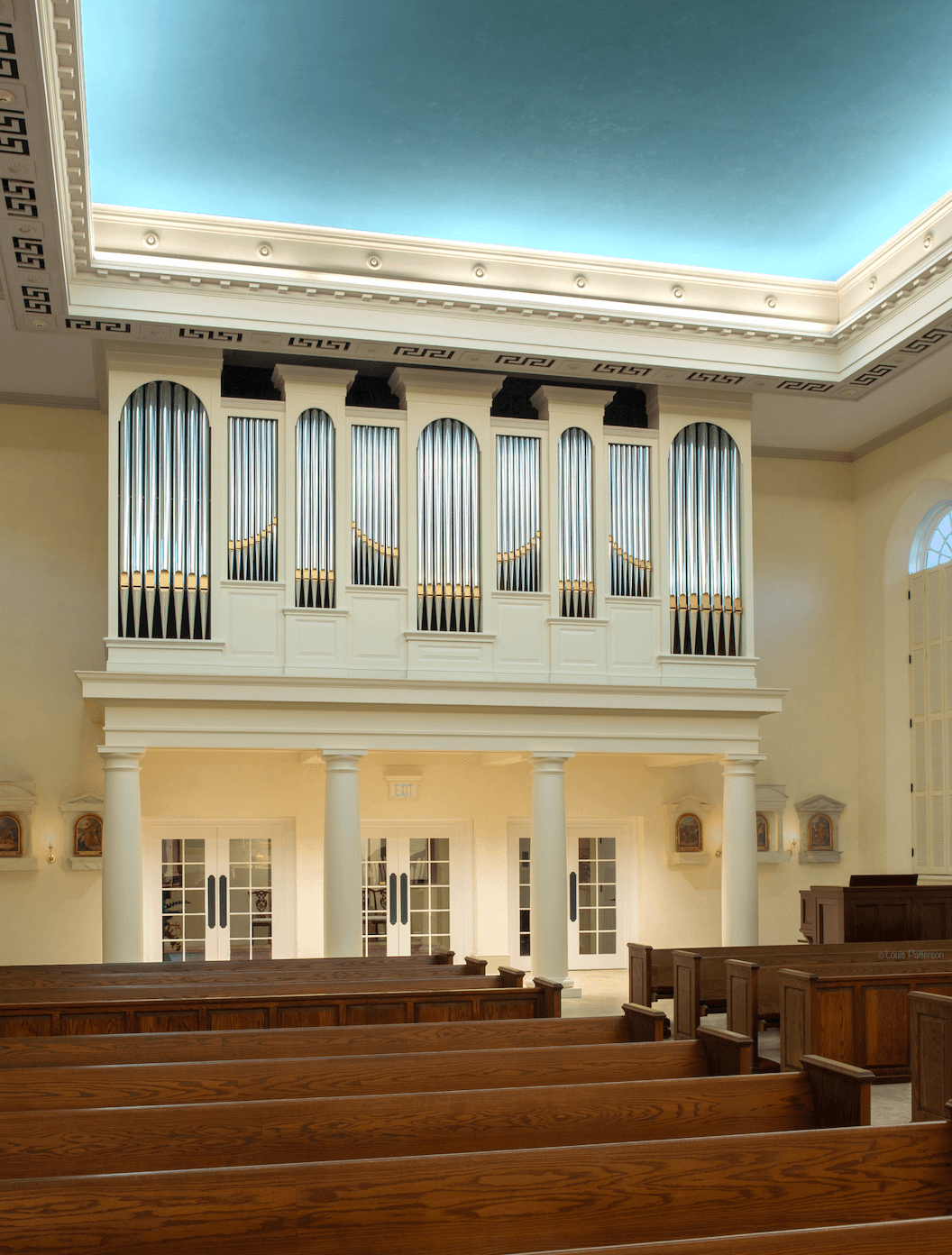

In 1977, the business was sold to a new owner named Jack Bethards, who expanded the national reach of Schoenstein & Co. The company’s illustrious pipes appear at Georgetown University and the Nashville Symphony Orchestra as well as dozens of churches including St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Palo Alto and St. Denis Church in Menlo Park.

Ed remembers working on San Francisco pipe organs with his father, including ones at the Civic Auditorium and the Legion of Honor. Those experiences in mechanical engineering, along with an education from Lick-Wilmerding High School, guided Ed to his first job designing bucket elevators at age 18. He went on to work for Bechtel and served in the Marine Air Reserve before turning to a career teaching drafting and eventually technical art at the College of San Mateo for 33 years.

Pat was raised in northwest Indiana and attended art school in Chicago for illustration. She drew fashion advertisements for newspapers in Chicago and later worked in student affairs at Notre Dame de Namur University. After moving to San Francisco, Pat was at a social camping weekend in Pinecrest when she met Ed. (He likes to say that she accidentally stepped on him while he was lying in his sleeping bag.) Today, two photos of the couple on the day he proposed to her at the Legion of Honor adorn their wall alongside photographs of their three adult children and a new generation of grandchildren.

Their home is filled with a lifetime of kept treasures including a ticket to the 1939 World’s Fair on Treasure Island that Ed attended when he was six years old. He remembers riding the ferry to the island and admiring the China Clipper, one of the largest airplanes of its time.

Ed’s fascination with the aircraft never faded and inspired him to create a model airplane of the China Clipper as a gift for the Treasure Island Museum about four years ago.

“I was hoping to stir up a little interest and try to get San Francisco to recall more of that Fair,” he says. “The 1915 Fair is much better remembered but the Treasure Island Fair was enchanting. I remember the soft, romantic colors at night. It was beautiful.” The models didn’t stop with the China Clipper and Ed has also produced faithful recreations of other parts of the Fair including the majestic Tower of the Sun and the Elephant Tower.

Looking over the now neatly compiled archives of their family history, Ed and Pat exude a hard-won calm and tranquility. The printed materials, photographs, journals, ledgers and letters that they sorted through and processed allowed them to document a tangible family tree, one with firm roots and endless new leaves.

In their project statement, they summarize reflective sentiments by writing, “How profound it is that we cannot see into the future and know the effects of our life on the lives that follow.”