Words by Johanna Harlow

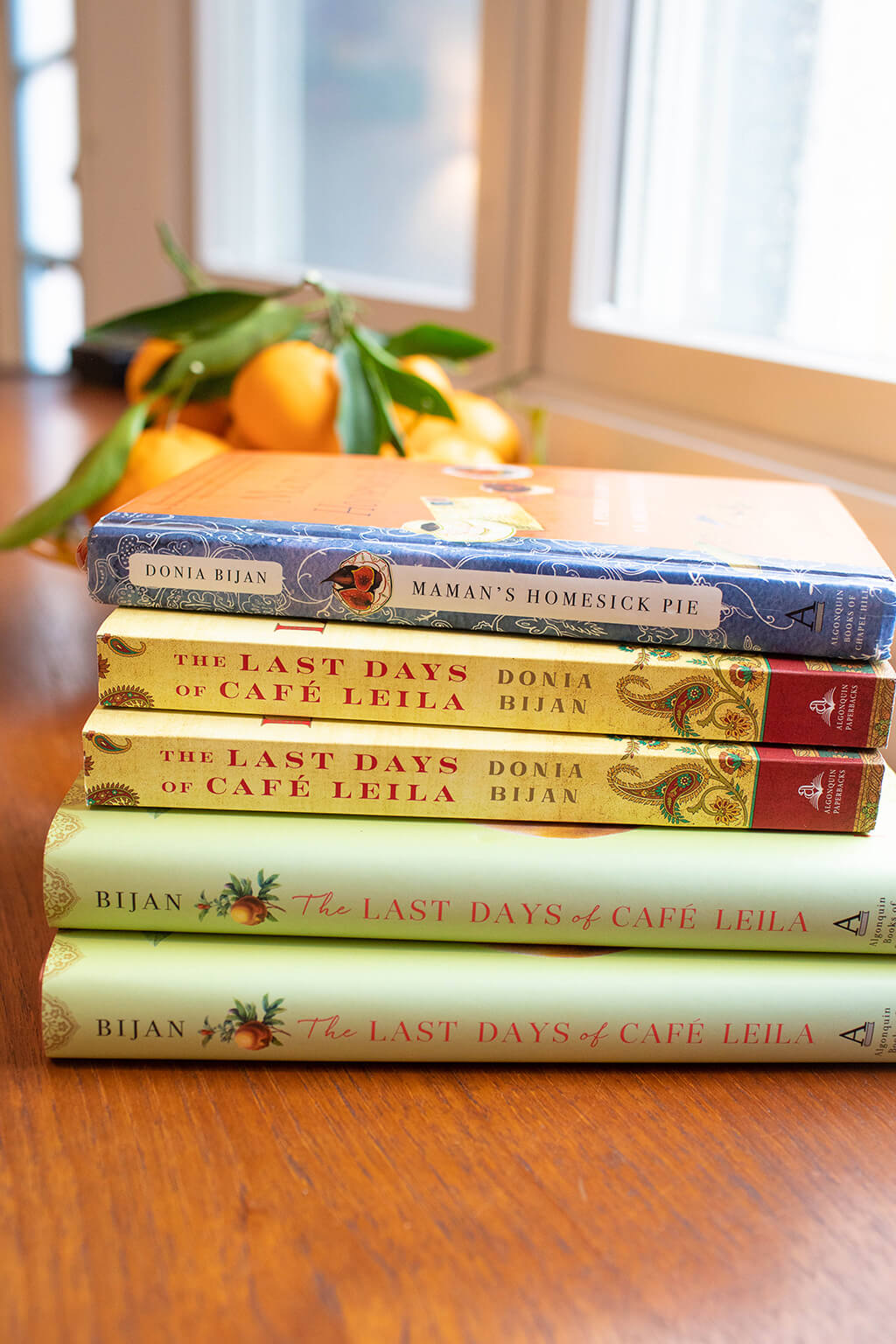

Immigrant, chef, author. For Menlo Park’s Donia Bijan, these first two identity markers weave intrinsically into the third. The Last Days of Café Leila—Donia’s novel about a woman named Noor and her return to her family’s restaurant in the beautiful but brutal city of Tehran after spending most of her adult life in the Bay Area—is flavored by Donia’s own experiences leaving her birth country on the eve of the Iranian Revolution as well as her culinary education and decade-long run heading Palo Alto restaurant L’Amie Donia.

Like your character Noor, you moved to the U.S. as a student. Can you tell me about that experience?

I came to America in 1978, on the cusp of turning 16. When you’re that young, you’re more resilient. But later, when my parents immigrated, I never stopped to ask them, “What was it like to lose your homeland?” At 16, I was self-involved and thinking, “Do I have the right jeans?” So in my writing, I’m asking the questions I wish I’d asked: “What was it like to start from nothing?” “What was it like to build a whole new life in a new place?” I will probably always write about exile and homesickness in different contexts because those questions are not resolved. I want to keep exploring them.

How was working in the restaurant industry?

Restaurant work is like war. You’re always on, you are likely to get wounded and you’re under tremendous pressure all the time. You run from fire to fire. There is very little contact with the world outside the restaurant. My husband always teases me: “Oh yeah, this song came out when you were in ‘The Cave.’” I have no idea about pop culture between 1986 to 2004 (when I closed L’Amie Donia). I was sucked into the vacuum of the restaurant world.

So what kept you coming back?

Oh, I was in love with it. The intensity. The pressure. Ultimately, you fall in love with what you’re cooking. You have this love affair with the dish. Each time you make it, it’s the first time. It’s a high because when you fall in love, you’re swept off your feet—but then you have to say goodbye. It’s like a Casablanca moment because that dish belongs to somebody else who’s paid for it, and you send it away and you’re left longing for someone else to order it. And it happens again and again and again. It’s indescribable.

You returned to France later in your career to further hone your culinary skills. How was that?

I worked for three months at different Michelin restaurants. After a few weeks, the chef would say, “All right, you’ve seen everything here. Do you want to go work for so-and-so? He’s near Provence.” Or, “He’s in Milan.” And I would get on a train with my knives and show up. At one stop, I remember the owner of a laundromat loaned me an iron for my uniforms. Until then, I’d been putting them under the mattress to smooth them out. Every night, after service, as if in prayer, I knelt by my bed and ironed my chef’s coat and trousers. Those are the memories that really stick with me because it felt like I was having a religious experience. I was a monk, and this was what I had to do to reach the next level.

In the past, you’ve compared making menus to poetry. Can you unpack those similarities?

Composing menus combined my love of writing with my love of food. The idea for a dish would come to me from one ingredient. I waited for it, and it arrived in the form of a sprig of lavender or an apple. I used the analogy of poetry because poems distill an experience. One dish can capture the essence of fall. And so I saw each dish as a little haiku, that would sort of transport you into the season. You’d be like, “Concord grapes… October… Of course!”

It reminds me of character development—the inkling of an idea and how it expands.

I never thought of it that way, but you’re right! So often someone will stop me on the street and say, “Rabbit! I always ordered that rabbit dish.” It was like they were talking about a person they looked forward to seeing every time they came in. And how each time it was a little different, but essentially the same. I closed L’Amie Donia in 2004, and people still stop to tell me how much they miss a certain dish.

How is restaurant work in contrast to writing?

I thought I was a hard worker and a very disciplined person.But writing—sitting down at a desk and being still and stringing words together—is so much harder than cooking for 200 to 300 people a night! A good day is when I can feel the characters in the room with me and we’re writing this story together. They’re guiding me and saying, “Do this. Don’t do that.” “I want to go here, not there.” And my job is to listen. A bad day is when they don’t show up and the silence is deafening.

In your book, food is linked with family as well as culture, community and memory. Why is that?

In my world, they’re inseparable. I think in many homes, the kitchen is sort of the epicenter, the heartbeat. I loved spending time with my mom in the kitchen. A lot happens there. You’re being nourished in so many other ways than just with food. The word in Farsi for stomach and heart is the same. Maybe that’s a subliminal thing in my head. They’re always connected.

How did you create the characters of Café Leila?

I had these three people—the father, the daughter and the granddaughter—as this triangle in my head for a good two or three years. I would hear the three of them knocking on my window. “We’re still here! What are you gonna do with us? We’re still interested in this project.” And I would be like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” Then I opened the door an inch and let one of them in. They were almost fully formed! To this day, I wonder where they came from.

Do you have a good support system backing you?

It was my husband [the artist Mitchell Johnson] who encouraged me to submit my writing. He has been a champion believer from day one. Each day, his parting words as he walks out the door to go to his studio are, “I can’t wait to read your book.” Every writer should be so lucky.

I know you’re working on a new novel. How have you seen your writing evolve?

I learned that a novel has the potential to feel like a home. When someone comes to your house, you don’t leave them standing on your doorstep. You invite them in for tea! Early in my writing, I wasn’t letting readers inside. You’ve got to let them see the raw emotion. It’s okay if the pillows aren’t arranged perfectly on the couch or the flowers in the vase are half-dead. A real person lives here. So open your heart and let ‘em in!