Words by Sheri Baer

Growing up in the Bronx, as the son of working-class Catholic parents who immigrated from Sicily, Dr. Philip Pizzo could never have imagined the twists and turns his life would take. “Nope! Not even slightly,” he attests. “I would say there probably were no predictors in my early life that indicated where I was going to wind up or how things were going to go.”

If anything, an expulsion from elementary school triggered deep concerns about a very questionable future. Through self-learning and a passion for reading, Phil successfully corrected his course and made a pivotal discovery. “On a personal level, I love change,” he says. “I love to learn and do new things. And so I’ve really relished changing directions on a regular basis.”

So much so that Phil has consistently and deliberately instigated change—becoming a model for risk-taking and even founding a Stanford program that encourages big leaps.

Phil’s insatiable quest to explore what’s next led to a storied career in medicine, research and academic administration. At the National Cancer Institute (NCI), he pioneered life-saving advancements in the treatment of childhood cancer and HIV. After two decades at NCI, he took the reins as the physician-in-chief of Children’s Hospital in Boston and then moved on to chair the Department of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

Photography: Courtesy of Stanford Medical Center / Cover: Courtesy of Saul Bromberger

Embracing upheaval again, in 2001, Phil switched up coasts to accept the position of Dean of Stanford University School of Medicine. And when he announced his plans to step down in 2012, Phil’s own search for his next chapter inspired the creation of Stanford’s Distinguished Careers Institute (DCI), a program that promotes mid-life reflection and recalibration.

Along the way, Phil authored more than 615 scientific articles and 16 books. As an advocate of lifelong learning, he also voraciously reads (or listens to) countless titles, while running 50 to 70 miles a week and logging two to three marathons a year.

Now 77, married to his longtime partner Peggy (an early childhood education and public policy expert whom he met as a college freshman) with two daughters and four grandchildren, Phil is leaving his role as founding director of DCI. Not to retire—but to attend rabbinical school.

After converting to Judaism with his wife (following a period of soul-searching and study), Phil’s next pivot will be training to become a rabbi. Embodying a lifestyle marked by steady waves of transitions, Phil’s approach represents the antidote to obsolescence. “It’s a function of being receptive to new things that enter your life, that allow you to rethink who you are,” he explains. “Sort of the path not seen but then chosen.”

Given that change is frequently a daunting prospect, PUNCH asked Phil to share some insights during a rare pause in his schedule.

Why did learning become such a powerful influence in your life?

Having grown up in an immigrant family, in a working-class environment, I kind of had to find my own way. I got into trouble in elementary school and got expelled and that was the beginning in many ways of my personal transformation. I remember the reflection on the event, which was, ‘Your life is not going in a very good direction.’ I knew the one way out was to learn, and so I began doing that. I found the community library, and that’s where, as a young teenager, I began finding my personal role models, who turned out to be people who made discoveries or who contributed societally in different ways. And that became the guidepost for things that continue to evolve in my life. So self-learning, self-guidance, were early elements for me in a very personally definitional way. Threading this through my life, whenever I’m facing a new challenge or interest, my first approach is to learn as much as I can.

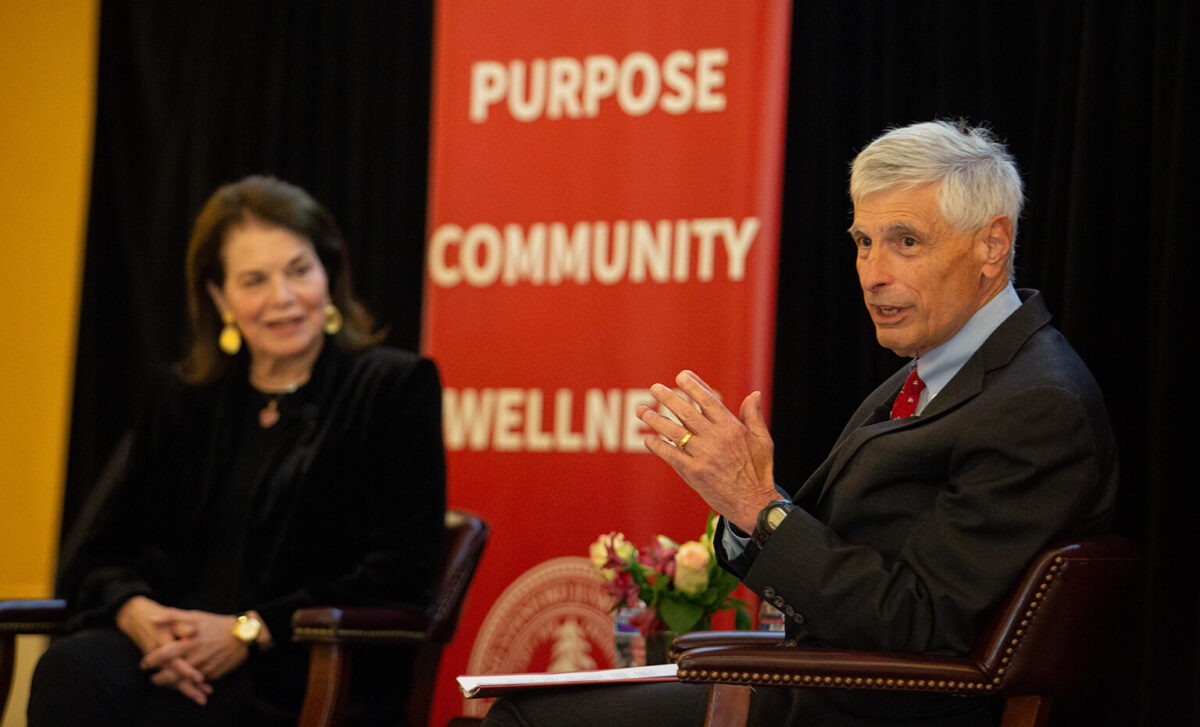

Photography: Courtesy of Linda A. Cicero – Stanford News Service

What’s your personal prescription for implementing change?

I’ve become more methodical in my thinking, meaning I try to make a significant change every five and not more than ten years. Of course, you’re doing that anyway early on. When I began my work life, I kept saying every four to five years I’m going to shift the direction of my research in new and different ways. It’s probably a bit of just needing new stimulation and a new challenge, and it’s also motivated by not wanting to get stuck. I’ve watched so many people who stay very focused in a line of research or inquiry or academia, and they wind up over time defending what they’ve done because the world starts moving beyond them. My solution to that is if you keep moving on, you don’t have to defend the past because you’re always going to be creating a new future.

Given that you’re starting rabbinical school at the age of 77, what’s your take on the concept of retirement?

We’ve got our three-part narrative: you get educated, you work and then you retire. Retirement is something that needs to be rethought. It’s not that I’m negative about retirement. I think that people want to do something different but just pausing completely and not having anything that inspires you is not a prescription for a healthy outcome. We’ve also put the point of retirement artificially around ages that are no longer relevant. I think it’s more important to think about the life journey as being a continued set of opportunities that you do throughout your life until you can’t. And that’s the way I have tried to guide people, and in many ways, guide myself. If you don’t have a sense of purpose, then you don’t have a sense of direction.

Why are you such a strong advocate for lifelong learning?

This is a really critical thing for us to rethink. Is there a reason why we only think about education at the beginning of a life span as compared to periodically recalibrating people’s lives throughout its course? We should have that same renewal opportunity for older adults, so that they can take an acceptable pause and more deeply reconsider where they’re going and make choices that are meaningful. By rethinking the role of higher education and having opportunities for people to come back to school—whether it’s for a little bit of time or a longer time to renew their life experience and knowledge—we can prepare them for another set of opportunities. DCI and similar programs that are following it are prototyping the importance of lifelong learning.

Photography: Courtesy of Stanford University School of Medicine

How are the founding principles of DCI tied to longevity?

When I started this new program about life transition, it was parenthetically built upon what I consider to be the three fundamental pillars of longevity: renewing purpose, building community and recalibrating wellness. It’s very important to have a sense of purpose, to know what your direction is going to be and renew your purpose periodically. It’s critical to have a community, a group of people who support you and engage you and whom you engage with. And it’s critically important to focus on wellness from a physical, emotional and spiritual perspective. There’s a lot of data that supports each of those as independent contributors to healthy outcomes.

You seem to have a fearlessness when it comes to change. What’s your advice to people who are a little less courageous?

I think you’ve touched on a core issue, which is so true: People fear change. And so they get co-opted into avoiding it and wind up making compromises along the way. I’m always reminded of an incredible woman whom I met years ago, Elizabeth Glaser, who was a fundamental child advocate for pediatric AIDS. She gave me a picture with a quote that said, basically paraphrasing, ‘When you come to the precipice and you need to jump, don’t be afraid. Jump and you’ll have wings.’ I’m being a little supercilious, but in a way, I think you have to jump, you have to be prepared to take the chance. And if you do that, I think almost invariably, people land in new and in many cases, happier places.