words by Sheri Baer

Mirang Wonne didn’t set out to trailblaze a new form of artistic expression. Truth be told, it was a matter of self-preservation. In 2009, she began tinkering with a new medium—stainless steel wire mesh—for a solo exhibit, envisioning an installation involving translucent light and lanterns. “I started to work,” she recalls, “and the edges were so sharp, they really cut my skin.” Deeply passionate but not quite willing to bleed for her art, Mirang asked a sculptor friend for solutions. He suggested using a propane torch, and when he applied a small flame to the harsh material, “Whoosh,” the wire mesh edges softly melded and smoothed. But that’s not all.

“It also turned unexpected colors,” Mirang says, “and I thought, ‘Wow, that is amazing! Forget about the lanterns!’”

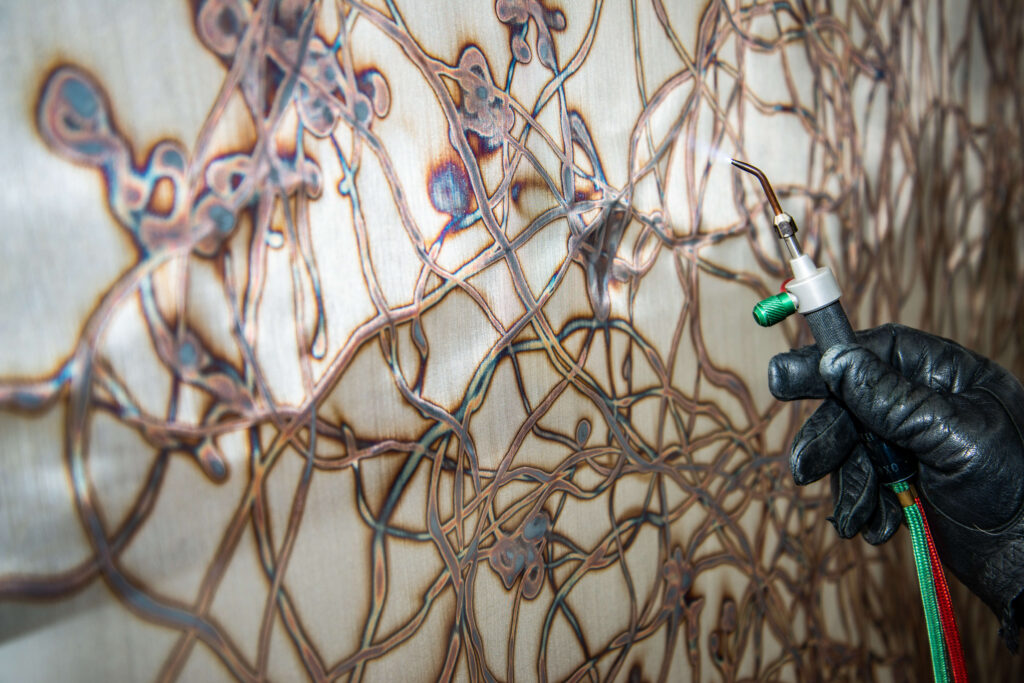

Intrigued by the possibilities, Mirang began to explore an uncharted creative path. She quickly ruled out a welding torch. “You burn the whole thing,” she discovered, before experimenting her way to a finer blow torch tip, more like a jeweler would use. By 2010, Mirang was ready to exhibit the first works of her invented artform—which has evolved over time into a signature style of torch painting on stainless steel mesh. “There’s no instructions; nobody knows how to do this,” she notes. “Even the supplier asked me to send some images. They don’t understand what I’m doing. They were so surprised.”

In a converted garage studio in Atherton, surrounded by canvases, paintbrushes in every shape and size and rolls of industrial mesh, Mirang dons protective eyegear and thick, black leather gloves. “This is propane and now this is oxygen,” she says, as she carefully adjusts two valves, triggering the eruption of a small flame from the torch in her hand. “You can adjust it to sharper or less sharp,” she explains. Turning to a screen of wire mesh suspended from the ceiling, she begins to draw with fire, a fluid weave of swirling, flowing red lines, which morph into shades of blues and browns as the amalgam of different metals react to the heat. For Mirang, it’s a deeply meditative process. “The bright tip of the torch seems to be alive,” she says. “The flame pulls my hand where it wants to go.”

This unique free-handed technique is a natural extension for an artist who has never felt constrained to draw within the lines. Born in Seoul, South Korea, as the youngest of six children, Mirang started elementary school two years early, and as her older schoolmates practiced origami, she enthusiastically wielded pencil and crayon—on any surface she could find. “I drew on the walls inside and outside of the house,” she confesses with a laugh, “and my parents never scolded me for my graffiti.” By about the age of six, Mirang knew she was going to be an artist: “I didn’t want to sit down. I always wanted to be doing something with my hands. I’d draw eyes and noses and I’d finish with my name, Mirang Wonne.”

Following accomplished BA and MFA degrees in painting from Seoul National University, Mirang earned a scholarship from the French Government Grant for Arts. She lived in Paris for nearly six years, completing a degree in mural painting and ultimately a PhD in aesthetics from University of Paris 1 (Sorbonne). After a brief return to Seoul to teach at her alma mater, she moved to New York, where she worked as a creative director, before getting married in 1984 and uprooting to her now longtime home on the Peninsula.

The dramatic shift in scenery and priorities required a major adjustment. “At the beginning, I would wake up every day and see all this same blue sky,” she recounts. “I didn’t know what to do —everything felt so different from New York.” A son and daughter soon followed, and Mirang found herself devoting all of her energies to her young children. As years slipped by, she felt the essence of her very being slipping away. “I make art for me,” she says. “I have to work and without work, I’m so miserable. It’s like how birds have to sing.”

Committed to rekindling her dormant creativity, Mirang secured space at the Hunters Point Shipyard Studios in San Francisco and settled into a routine: Drop the kids at school. Drive up to the former U.S. naval complex-turned-art-colony. In the decades that followed, she evolved her art through experimentation and instinct. After working monochromatic for a while, “Something inside me says I need some color, and then I think I’d like to see more depth, so I add a second layer so the lower screen will see through. And then I think, ‘What else can I do?’” she says.

Although she still maintains her Hunters Point studio as a personal gallery, Mirang finds her home studio better suited for artistic exploration. About six years ago, her work with stainless steel mesh led her down yet another path: “Since the metal is silvery, it’s beautiful, but I thought, ‘What if I add pure gold to it?’” After months of failed attempts, Mirang successfully mastered the centuries-old gilding technique, applying 12k, 18k and 24k gold leaf directly to the metal screen—golden accents evoking botanic, arboreal and even oceanic themes.

Since her very first solo exhibit in 1973 in Paris, Mirang’s diverse art forms have attracted private collectors, along with being collected and shown in numerous museums and public spaces such as Musee d’Art Moderne de Paris, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco Asian Art Museum, Seoul City Museum, Triton Museum of Art in Santa Clara and the de Saisset Museum at Santa Clara University. Her de Saisset exhibit caught the eye of Stanford Health Care, which commissioned large lobby installations and major paintings for its new Stanford Cancer Center construction in San Jose. Mirang lost her husband to brain cancer in 2011, so the project came at a particularly meaningful time.

Mirang completed the commission in 2015, a collection of soothing four-season themed paintings and California Light, a freestanding 15-foot by 12-foot massive stainless steel mesh installation. Requiring 17-foot screens, the project prompted Mirang to cut up into her ceiling and install a pulley in the attic. With four overlapping torched panels, the final artwork couldn’t be fully assembled and viewed until it was completed. “It was impossible to see in my home studio, so it was such a scary moment,” Mirang says. “But the installation looks beautiful and I feel so good about it.”

Although Mirang finds personal fulfillment in the creation of art, she embraces the free-flowing nature of interpretation. “There’s something very different between the artist’s and the collector’s view,” she observes. “Sometimes they see something very different from what I was thinking, and it’s the artwork talking directly to them.” With close friends beginning to retire, Mirang remains grateful to have an artistic outlet that sustains her—and the Peninsula’s natural beauty to inspire her. “I just want to say thanks to California and California sunlight,” she says. “I’m so lucky to live here. I tell my children to appreciate that they live in paradise.”