The door into Neil Murphy’s art studio is often open for visitors to come inside and have a look.

The lifelong mixed-media artist in his early 70s is more accustomed to working out of a home studio where guests were uncommon but he’s challenging his self-described introverted tendencies by inviting Peninsula visitors to observe his renderings of shape-shifting subjects at the Museum Studios in Burlingame.

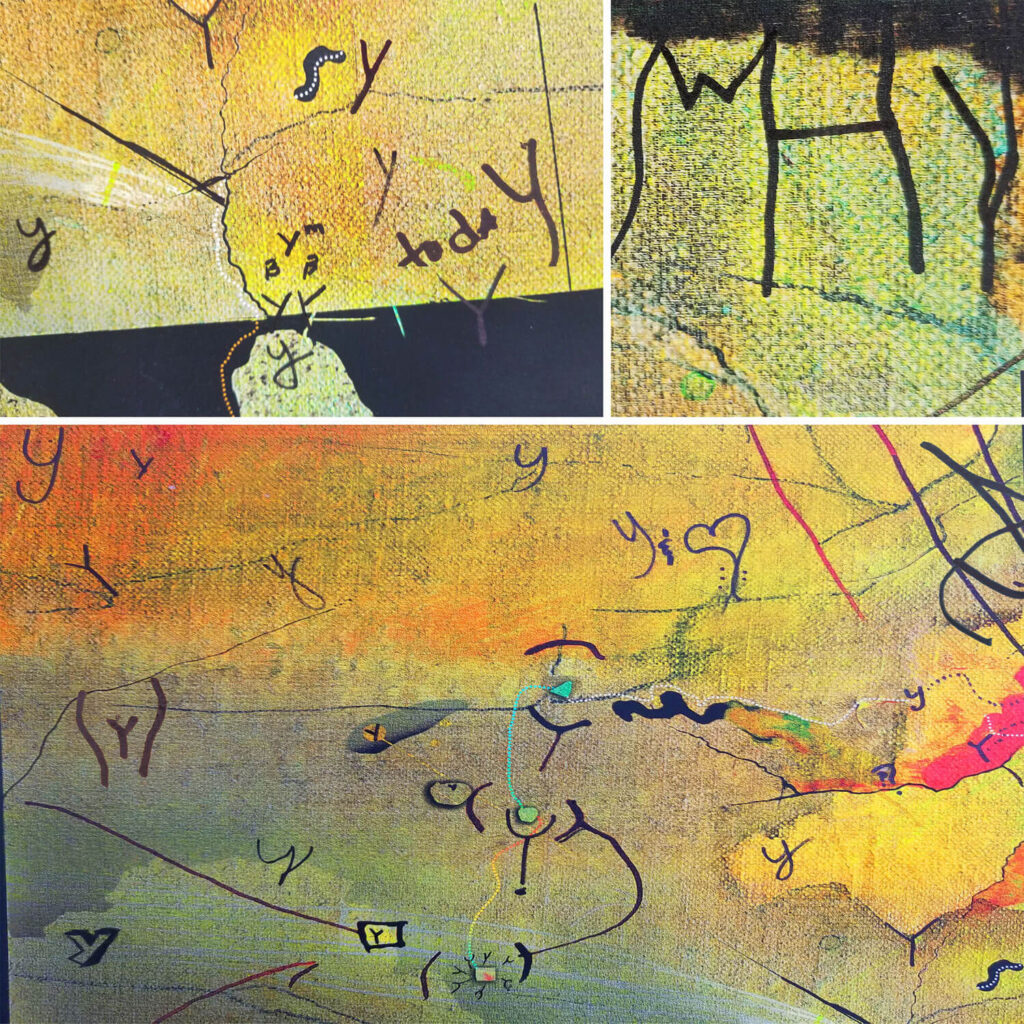

His artistic explorations tackle abstract maps of neurological messaging or visuals that reflect patterns found in the natural world, such as the pristine spiderweb he discovered inside a black bucket in his backyard garden.

The most recent exhibit, shown earlier this year, You Can’t Hide the Sun with One Finger, featured a piece focused on mountain ranges (Or were those ridges splintering across the shell of the cerebrum?) sketched against an amber backdrop. He suspended several puzzle pieces outside the image’s rectangular border to form a swarm of figments buzzing about the canvas, followed by black lines to trace them back to the heart of the painting.

Neil will tell you with openness and vulnerability, in a manner that’s been stretched by grief, how this art piece is a commentary on psychological confusion, a human condition that touches all of us, either personally or through someone we know. However common, mental illness is often ineffable to discuss and shrouded in shame.

The puzzle pieces Neil deployed, after all, were forging new pathways and ideas, even if deemed outside of what’s normal.

His art is his way to add a voice to the struggle of destigmatizing mental illness, dissolving discomfiture through the disinfectant of shining a light and opening a dialogue. The intensity of the subject is disarmed by Neil’s calm affability and ability to approach heavier concerns with grace—a technique he deploys in conversation as well as on canvas.

“I’m fascinated by how the brain works,” Neil says. “When people come into my studio, I’ll mention how my son had a mental illness before he died and how our culture doesn’t make room for such people. Every single time, the person I’m talking to will say they have an uncle, or neighbor or some family member experiencing the same thing. One out of four of us has a mental illness. It opens the conversation, and then, all of a sudden, I have a new friend.”

Neil’s studio is located in the upstairs east wing of the Museum Studios, under the umbrella of the Peninsula Museum of Art in Burlingame. Cinder blocks and wood, in the likeness of a college dorm room, connect to make shelves stocked with brushes, aerosol spray paints, art books, a half-used roll of paper towels and a wooden human mannequin posed in a courteous bow.

The white walls compete for space between Neil’s rectangular mixed-media art pieces he creates through a process that blends the digital with the physical.

Neil begins by painting an image that springs to mind—from ships at a distance to cranes before flight to geometric masses of color—before scanning it for a digital metamorphosis through Photoshop.

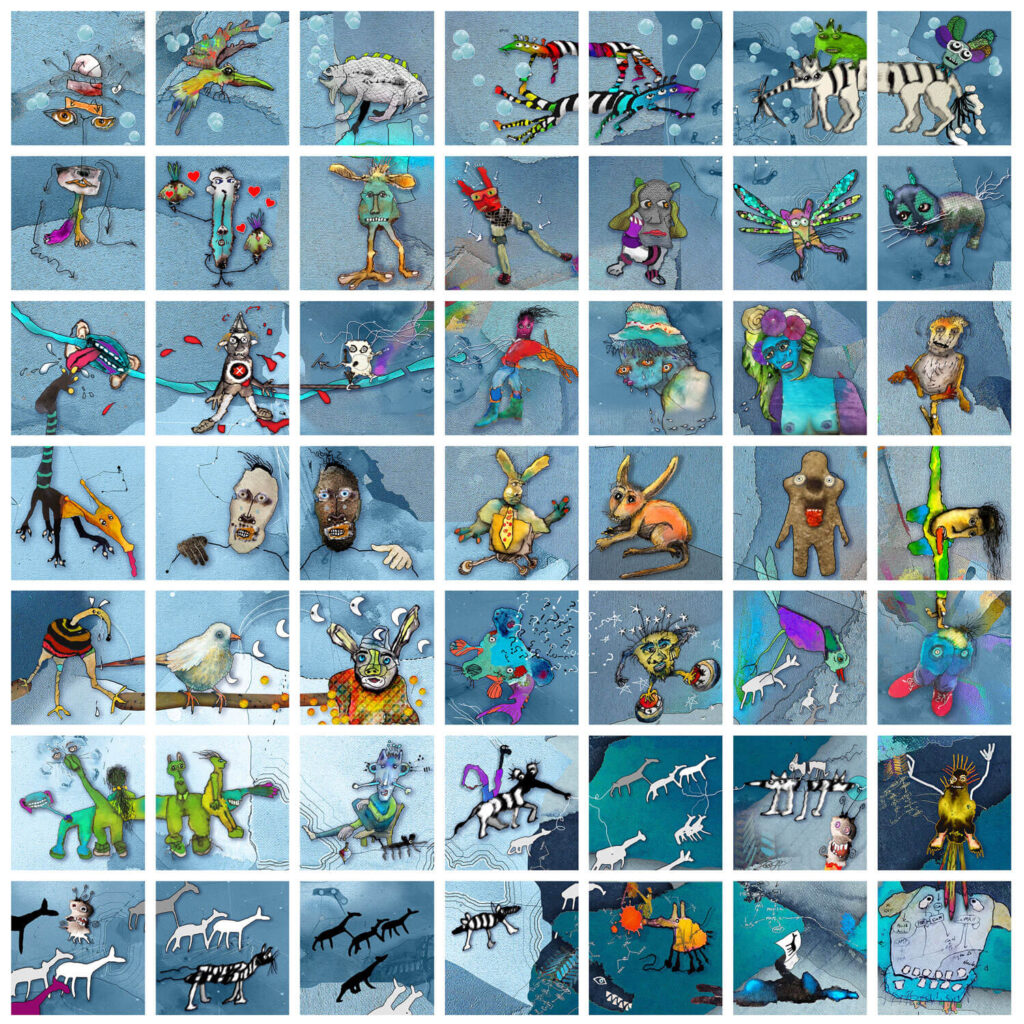

Then, he repeats, adding layers and textures in cycles before concluding with an image composed of relatable shapes or creatures that have been completely rendered by his imagination. The unusual images of such an otherworldly perspective may feel jarring or confrontational at first glance, although are quickly softened by the warm colors and whimsical details.

There are about 200 pieces currently in his studio and Neil makes both private and commercial sales, often after someone visits his space. His art appears on walls of local biotech companies and even local coffee shops but a majority of his art is located in private residences.

Not long ago, Neil welcomed a visitor into his studio from the local Kids & Art program, which pairs artists with children who have cancer to use art as therapy. His visitor was initially hesitant, telling Neil he didn’t know how to draw. But Neil knew the fundamental rule in art.

“He said he liked red, so we started by putting a blotch of red on a piece of cloth,” Neil remembers, excitement growing. “Then I asked him what color his best friend likes, which was blue, so then we made a blue door. Next, he drew a line. Now we’re starting to make a map and he doesn’t even know it. This thing evolves and we keep making lines and graphs. In the end it had airplanes dropping candy over the candy store,” Neil pauses.

“There are no rules in art,” he states.

Neil’s artwork has reached across continents to offer joy and comfort in hallways otherwise devoid of such emotions. He’s installed a three-panel display of birds circling in flight at the Kaiser Permanente in Redwood City and his collection of Bad Beasts was selected to appear on the walls of a new pediatric cancer hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. None of his little beasts appear happy or comfortable—an aspect drawn with purpose.

“It’s not Donald Duck,” he says. “These creatures look miserable and children undergoing treatment for cancer can identify with that.”

As a child growing up on the Hawaiian island of O‘ahu, Neil spent much of his youth in solitude, exploring tidepools just down the block from his house. He’s the youngest of four boys with over a decade separating him from the brother closest in age, so spending time alone was constant and became comforting. Neil identified with it. He’d fish the tidepools where his tolerance for being alone embedded itself in his personality.

Following a year at the University of Hawaii, where he majored in “body surfing and Eastern philosophy,” Neil arrived at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1967. He saw the school as an opportunity for studio space but appreciated his lessons in stone lithography. “The rest of art, you teach yourself,” he says.

In 1974, Neil was part of a group drawing exhibition at the SFMOMA, where he showed a series of works depicting streams and water flow using architectural blueprints as his media. His first solo show was at the bygone Wenger Gallery the same year and following positive reviews, he began showing in galleries in Arizona and New York. He often experimented with audio in his art, inspiring a career composing musical effects for clients like Levi Strauss & Co. and even the Mitchell Brothers, for their notorious film Behind the Green Door.

By 27, Neil was living near the ocean by the San Francisco Zoo where he set up a sound studio in his garage, later leading to a six-year stint as production manager of National Semiconductor’s computer speech lab.

He met his wife, Juliana Fuerbringer, while playing on opposite sides of a tennis net and they welcomed their first-born, Brian, in 1988, followed by their daughter Morgan. Neil’s work at National Semiconductor in Santa Clara brought the family to Burlingame, where their home has featured numerous generations of dogs and cats over the years. Their most recent addition is a black feline with sharp teeth they’ve named Fang.

Some nights Neil can’t sleep and will find himself alone in his studio just a short drive away. He cherishes how the space has exposed him to the public; however, in the middle of the night, he readjusts to being alone surrounded by an idea, some paints and a computerized scanner.

He’ll begin working out his latest thought, toggling between the digital and analog to bring abstract interpretations into the light. When the Museum Studios opens to the public the following day, Neil will unlock his door and greet them.