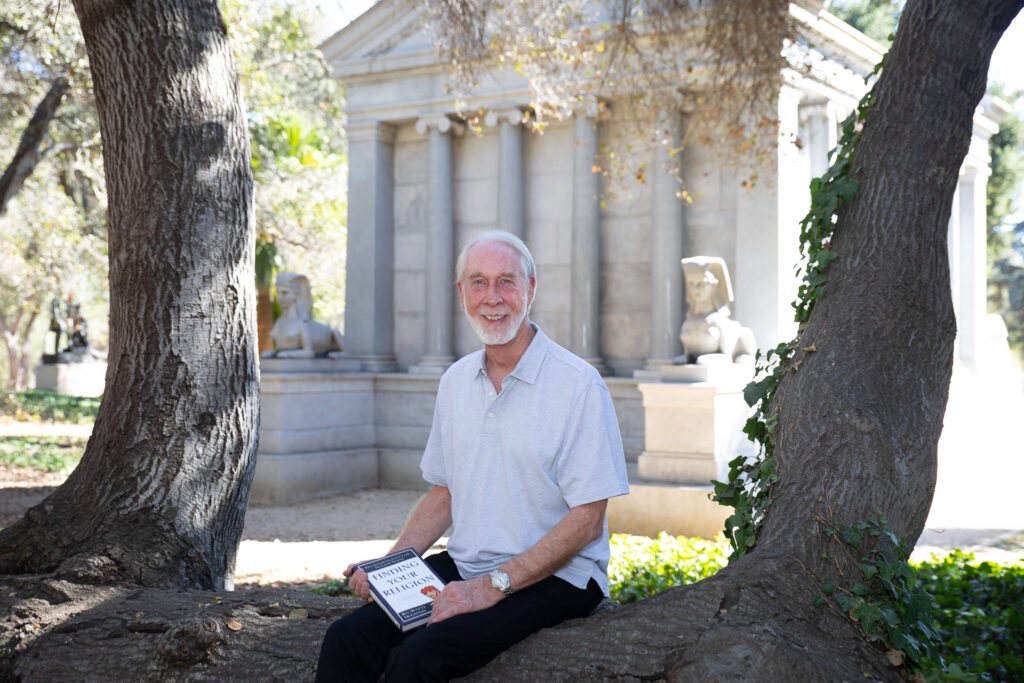

Author of four books. Attorney focused on poverty law. Unitarian Universalist preacher. Dean at two prestigious universities. Stanford Business School lecturer.

Sitting down with the Rev. William (Scotty) McLennan in his Menlo Park backyard, that seems like a lot to unpack. Not so, he explains: “In my mind, they absolutely connect. I’ve tried to build bridges across disciplines. To me, the ministry is the arena that relates to all of life, that allows for the inter-relationship.”

Originally from Lake Forest, Illinois, Scotty had an early fascination with the law and his interest in ministry grew steadily during his years at Yale University. “They represent two separate sides of the brain,” he notes. “Result-oriented/rational on one side and emotional/spiritual on the other side. I couldn’t do one without the other—but I’m basically a minister. I’ve just done that in a variety of contexts over the years.”

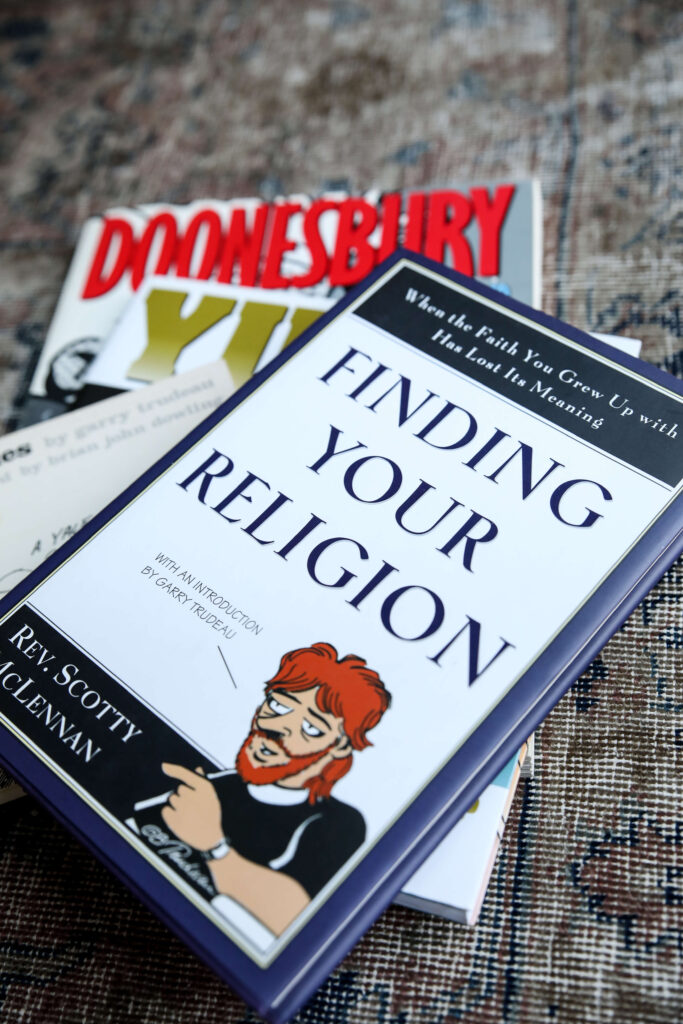

It was at Yale that a group of housemates, as Scotty describes them, left a permanent mark on his life. “Seven of us stay in close touch, meeting every Labor Day for 35 years until this year when we’ve been gathering via Zoom on Saturdays,” he relates. “Cartoonist Garry Trudeau was part of the group. He was focused on going to art school but he started a comic strip, Bull Tales, for the Yale Daily News.”

What began as Bull Tales launched as the daily comic strip Doonesbury in 1970, with Trudeau drawing inspiration from familiar characters in his own life. “The character BD is based on Brian Dowling, who was the quarterback of the football team and a big man on campus, although not a part of our group,” says Scotty. “We called Charlie Pillsbury ‘The Doone,’ so he was the basis for Mike Doonesbury. He looks somewhat like the character.”

As for Doonesbury’s streetwise priest and Walden College’s unofficial chaplain, the likeness is an immediate tip-off. “I’m the Rev. Scot Sloan character with bright red hair and beard,” acknowledges Scotty. “Mixed in with the character is my mentor, Yale chaplain the Rev. William Sloane Coffin.”

What’s it like to be forever immortalized in the funny papers? “Being a cartoon character is a great compliment,” he says, “but from time to time you realize you are a lifelong joke!”

For the record, Trudeau did go to art school. But he also won the Pulitzer Prize for Doonesbury and figured out that “being a cartoonist was a profession he could genuinely be proud of,” as Scotty explains.

As a graduate student at Harvard University, Scotty did something that no one before had done. He enrolled simultaneously at the law school and the divinity school. “I would run back and forth between the two schools,” he recalls. “The law was narrowing. Divinity school was broadening. But I couldn’t do one without the other.”

The goal upon graduation was social justice work. “This was a period when peace activists like the Berrigan brothers, both of whom were Catholic priests, and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., were in the news,” he continues. “They were all religious figures; it was the sense of religion being connected to social justice.”

Scotty was ordained in 1975 as a Unitarian Universalist minister and admitted to the Massachusetts bar the same year. He immediately went to work in what he describes as “legal ministry” in Dorchester, a Boston neighborhood. “In our work, we’d ask, ‘What is the life problem that led to your legal problem?’ The people we worked with were frustrated with the legal process and often alienated. We’d explain the legal process, but we’d also pray with them when asked to do so.”

Scotty found great satisfaction working with low-income clients who could be helped in a wide variety of ways, maximizing their income, dealing with family issues, negotiating with landlords and helping with consumer issues. “What was frustrating was the amount of time I had to spend in law libraries and courtrooms arguing with other lawyers,” he says. “It was a kind of chess game over people’s real human needs.”

Following his work in Dorchester with the Unitarian Universalist Legal Ministry, he served as University Chaplain at Tufts University for 16 years. While there he was invited to teach part-time at Harvard Business School’s ethics program. He saw teaching business school students as an opportunity to reach people “on the other end so that they can understand the real plight of low-income people and people of color,” Scotty explained in an article spotlighting Harvard Divinity School alumni.

Scotty continued the tradition of preacher and professor when he became Dean for Religious Life at Stanford University in 2001, teaching both undergrad and graduate students. A highlight of his tenure was meeting with one of his spiritual mentors, the Dalai Lama. “It was my honor and great pleasure to be part of two visits by the Dalai Lama to Stanford,” he says.

In 2005, Scotty moderated a public conversation with the Dalai Lama about the nature of nonviolence in the chancel of the Stanford Memorial Church. In 2010, he welcomed the Dalai Lama back to Stanford Memorial Church to deliver the Rathbun Lecture on a Meaningful Life. “In both cases he spoke in depth about compassion, altruism and the importance of nonviolence in all aspects of life,” Scotty recounts. “In my personal time with him I was amazed by his warmth, his down-to-earth approach and his sense of humor. He also seemed to be deeply attentive to everyone he met. He has a great ability to connect science and religion, modern medicine and spirituality, pragmatism and idealism and the sacred and the secular.”

Scotty retired as Dean in 2014 but continues to teach Stanford Business School students, making a practice of integrating novel approaches. “I love teaching and being with students in a classroom setting,” he says. “It’s just so much fun—and that’s been my retirement goal, to do things that are fun.”

In one course, students explore the experience of respected business leaders who have been able to integrate their spiritual and business lives successfully. Another examines the deeper levels of attitudes and beliefs, often unconscious, which lie beneath the way business is done in various countries.

“You can’t really do business in the United Arab Emirates without knowing something about Islam and you can’t do business in China without knowing something about Confucianism or in India without knowing something about Hinduism,” Scotty explains.

Over the years, Scotty has been disappointed and frustrated that students were not more involved with social justice issues like institutional racism. “They’d spend time at a homeless shelter but that was making it a personal issue, offering a band-aid solution,” he says. “But in the last few years I’ve noticed a shift with students looking at the institutional basis of poverty, racism and gender issues. That’s been promising.”

In addition to retiring as Dean, Scotty also retired as an attorney and as a minister in active service including his association with the Universalist Unitarian Church of Palo Alto. “There were all these things I hadn’t had time to do in my life,” he says. “The first and foremost was more time with my wife, children, grandchildren and friends.”

Although no longer on the pulpit, Scotty emphasizes that ministry remains at the forefront of his life: “Religion is about emotion and engaging with other people and about art and music and all those other ways of connecting with something grander than yourself.”