words by Sheri Baer

While 2020 will be remembered for introducing a pandemic lexicon all its own, look back 100 years and the local talk ran to rum runners, prohis, bootleggers, speakeasies and moonshine. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the 18th Amendment becoming law, banning “the manufacture, sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” From 1920 to 1933, the wild and unruly Prohibition Era profoundly impacted life across the U.S. With the help of the San Mateo County Historical Association, PUNCH turns back the clock—capturing the lingo, the local legends and the lawlessness—to better understand how this infamous period played out on the Peninsula.

Caper (slang): A robbery or other criminal act.

While the 18th Amendment prohibited the manufacture, sale and transportation of “intoxicating liquors,” the ownership and home consumption of alcohol was still legal. Peninsula residents had the year between the ratification of the amendment and when it went into effect on January 16, 1920, to purchase a supply of alcohol to enjoy when the country went “dry.” The millionaires of the area made sure the wine cellars of their great estates were fully stocked. A portion of W. M.

Fitzhugh’s Menlo Park cellar included 141 cases of imported whiskey and 68 cases of wine, brandy and champagne.

The Ocean Beach Hotel, Miramar

What is now the Miramar Beach Restaurant was originally designed and built as a Prohibition speakeasy—complete with revolving kitchen cabinets and other secret compartments for hiding illegal liquor. The upstairs of the Ocean Beach Hotel served as the Bordello. Running the show was a red-headed madam named Maymie Cowley, aka “Boss,” and the roadhouse was raided numerous times for illegal liquor, gambling and prostitution.

When Prohibition started, thieves met the demand for alcohol by “capers” burglarizing the wealthy. In late February 1920, S. W. Morehead lost two cases of gin, two cases of whiskey and 10 gallons of wine from his Portola Valley home. Posing as laundry wagon drivers and gas meter readers, one gang stole $20,000 worth of liquor in the first six weeks of Prohibition. In a famous caper, a gang of nine robbers held Julien Hart’s Menlo Park household at gunpoint for several hours on March 2, 1922. One robber told a hostage, “We believe that this liquor should be put in general distribution, so that everybody gets a chance at it, and not let the rich have it all to themselves.”

As Prohibition continued, robbers targeted more than the wealthy. Hijackers stole alcohol seized by law enforcement agents and hooch smuggled by bootleggers. In December 1924, a Pescadero gang stole a $20,000 cache of whiskey hidden by bootleggers. The bootleggers invaded Pescadero and roughed up the residents until the missing liquor was found.

On the Lam (slang): Evading the police.

“San Mateo County is the most corrupt county in the state.” This assertion from the Hillsborough mobster Sam Termini in the 1930s reflected years of Peninsula residents disregarding laws on alcohol and gambling. The 18th Amendment made the manufacture and sale of liquor illegal. Enforcement was difficult in San Mateo County where large parts of the European immigrant population believed drinking was a right. Other residents viewed Prohibition as an opportunity to make money or have some fun. Women joined the men drinking, smoking and gambling in illegal speakeasies or bars. Rum runners used the foggy coast to smuggle Canadian whiskey from off-shore ships. Throughout the county, everyday folk made moonshine.

The National Prohibition Act, known as the Volstead Act, made the Bureau of Internal Revenue of the Treasury Department responsible for the enforcement of Prohibition. The Treasury Department’s Prohibition Enforcement Unit had about 3,000 agents nationwide. They were known as “prohis.” In San Mateo County, these agents patrolled the beaches watching for rum runners and raiding stills. The Prohibition Enforcement Act, known as the Wright Act, made California police officers responsible for enforcing Prohibition laws. Many local police departments were small and not prepared for the demands of Prohibition. For example, South San Francisco had only four officers to police a community of 3,000 people. Despite numerous raids, the county was considered one of the “wettest” in the state.

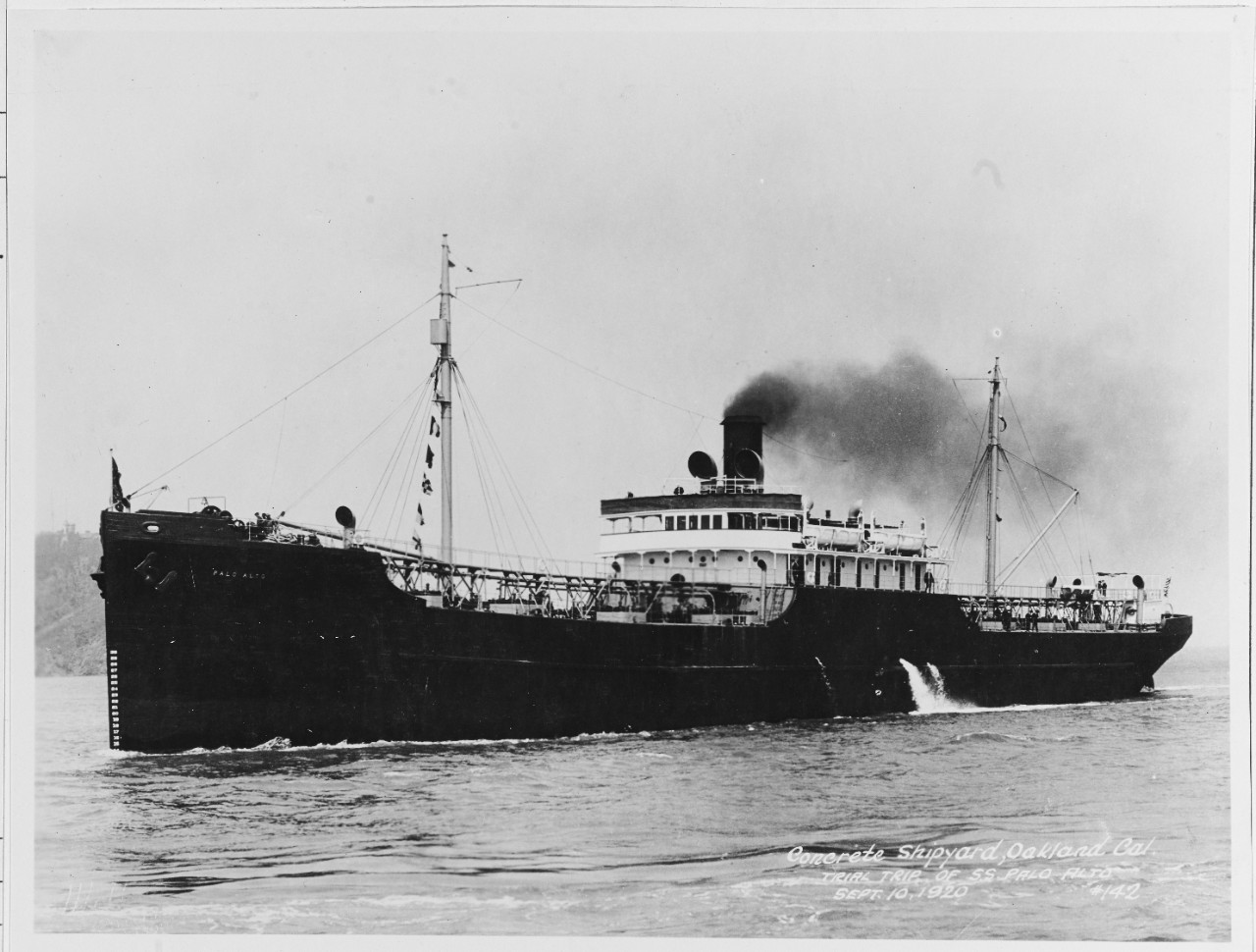

SS Palo Alto, Aptos

Visitors to the Seacliff State Beach fishing pier near Aptos are always intrigued by the mostly-submerged remnants (now artificial reef) of the SS Palo Alto, a concrete tanker built during World War I. In 1930, the retired vessel was transformed into a docked party boat known as “The Ship,” with a casino and cabaret above deck—and one of Santa Cruz County’s most notorious speakeasies down below. Big bands of the day, including Tommy Dorsey and Benny Goodman, played in The Ship’s Rainbow Ballroom.

Moonshiner (slang): One who makes homemade alcohol.

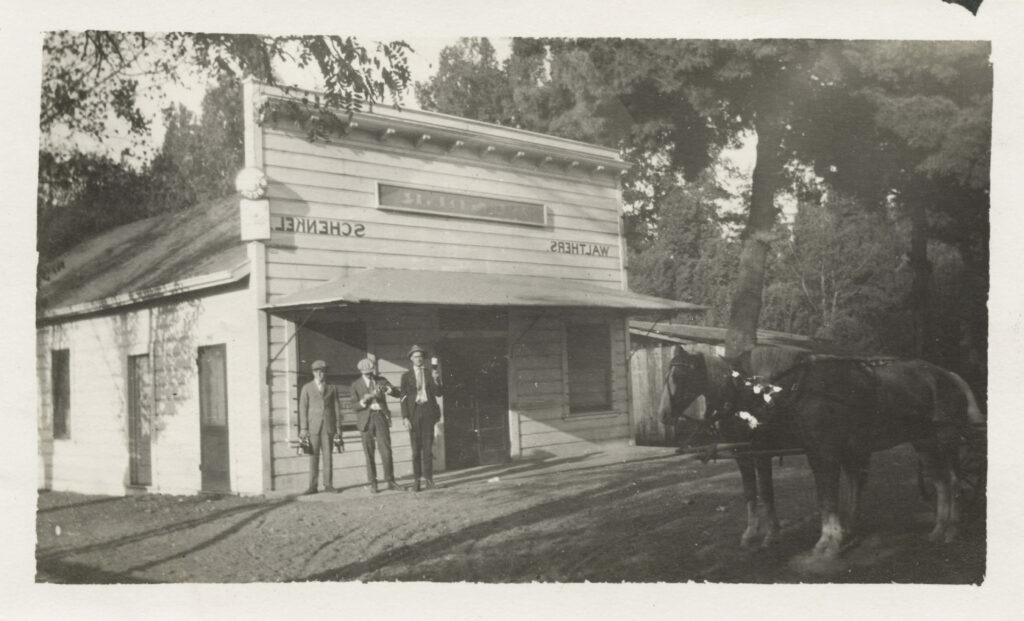

The 18th Amendment prohibited the manufacture of alcohol. All over the Peninsula, residents disregarded this law. Some European immigrants saw no need to discontinue making the beverages they were used to drinking. At a time when legitimate jobs paid 25 dollars a week, some found the money to be made by moonshining to be appealing. An experienced moonshiner could make a gallon of whiskey for 70 cents and get a return of 50 dollars at a speakeasy. Small distilleries flourished. Most were found in the basements of private homes. It was easy to get started as a moonshiner. Recipes could be found at local libraries. Ingredients such as grapes, hops, sugar, barley and yeast could be purchased in stores. Local newspapers advertised where one could buy equipment such as steam boilers, condensers and copper pipe needed for a still. Larger stills were hidden on farms or in local businesses.

During a 1924 raid on a San Bruno area ranch, the prohis uncovered a wholesale moonshine plant that possessed 5,000 gallons of mash and a double distillery that produced 125 gallons a day. In 1931, authorities discovered that the J. R. Soda Works in South San Francisco operated one of the biggest distilleries in California. Owned by the South San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, a spur line to the Southern Pacific Railroad was built at the factory’s loading ramp, which allowed it to supply alcohol to most of the Western states.

Some moonshiners were less skilled than others. Inexperience in production could lead to moonshine that was dangerous to one’s health. In 1921, Harold Johnson brought suit against three Portola Valley moonshiners claiming that their grappa had caused him a temporary loss of eyesight.

Moonshiners discovered that improperly run stills exploded. In 1928, a barn was destroyed when a 600-gallon still exploded in El Granada. Explosions such as that one drew the attention of authorities, leading to the confiscation of liquor, mash and equipment.

Rum runner (slang): A person bringing prohibited alcohol across borders.

With American wineries and distilleries officially closed, people saw a chance to make a fortune by smuggling alcohol. Rum runners filled their ships with whatever alcohol was in demand, especially Canadian whiskey. Many of the rum runners that anchored along the San Mateo County Coastside came from British Columbia. United States jurisdiction extended three miles, and later twelve miles, from shore. Large ships with illegal whiskey would anchor just outside the jurisdiction area on both the Atlantic and Pacific Coast, forming Rum Rows. From the Rum Row off San Mateo County, the alcohol was unloaded into coastal boats.

Some Coastside residents incorporated rum running in their daily jobs. One El Granada fisherman remembered taking his boat out in the afternoon to meet a small freighter that could carry 100 cases of alcohol from Canada. He could order a load of whatever he wanted—vodka, gin, scotch, bourbon or Old Crow—and be back to El Granada with his load in three hours. Often, the coastal boats landed in secluded coves. Bootleggers paid Coastside boys $100 to unload boats and load the bootleg onto trucks. While some of the liquor went directly to Coastside speakeasies, much more of it went to San Francisco.

Dry Times in Palo Alto

When it comes to the prohibition of alcohol, the city of Palo Alto holds the Peninsula’s “driest” honors. Back in 1886, when Leland and Jane Stanford set out to found a university, they approached the town of Mayfield (now the area of Palo Alto’s California Avenue) about closing its saloons. After being turned down, they founded their own dry college city, Palo Alto (including downtown University Avenue), which legally banned all intoxicating liquors within a mile and a half of campus. Mayfield kept the liquor flowing, only to be annexed by Palo Alto in 1925. Up until, through and even after Prohibition ended, Palo Alto stayed the course—with the local government forbidding the sale of alcoholic beverages. In the 1930s, nearby East Palo Alto in San Mateo County stepped up to meet demand, and the area was nicknamed “Whiskey Gulch” by Stanford students who frequented its popular liquor stores and bars. The 1.5-mile ban officially stayed on the books for decades—and it wasn’t until 1971 that downtown Palo Alto served its first legal cocktail.

The Coast Guard was responsible for catching rum runners by sea, but only two Coast Guard cutters were stationed near the San Mateo County Coast. Often, the fast, well-armed ships of the rum runners evaded and outran the Coast Guard ships. On shore, law enforcement and bootleggers engaged in violent confrontations. In 1923, federal agent W. R. Paget led a raid against an operation at Año Nuevo Island. Armed with sawed-off shotguns, the agents fought a gun battle until the bootleggers ran out of ammunition. Even when law enforcement managed to catch bootleggers, judges gave light sentences. In South San Francisco, Officer Augustine Terragno pulled over a car for running a stoplight. He discovered 25-gallon containers of alcohol. Terragno reported that “all the judge did was fine him for running the light…worse, I was told to haul all the booze back to the Buick!” After that, he did not bother to stop bootleggers.

Speakeasy (slang): An undercover bar; an illegal drinking establishment.

Speakeasies on the Peninsula numbered in the hundreds. High-class speakeasies in hotels and restaurants provided fine food and entertainment, along with moonshine and bootleg whiskey. Located in barber shops, grocery stores, cigar stores and soft drink parlors, many “speaks” were much smaller. A password granted access to a small back room with a bar and perhaps some card tables and slot machines. Customers paid 50 cents a shot for moonshine and up to two dollars for whiskey.

While women rarely entered bars before Prohibition, everyday “dames” frequented the speakeasies. In addition to being regulars, there were “whisper sisters,” such as Maria Mori, who helped her husband operate a speakeasy at the Sanchez Adobe.

Speakeasy owners obtained their alcohol from several sources. Some proprietors, such as Manual Bernardo at the Beach Inn near Half Moon Bay, had their own stills. Also on the Coastside, both “Boss” John Patroni at Princeton and Jack Mori at Mori’s Point had private wharves near their speakeasies for the delivery of whiskey. While law enforcement agents did raid speakeasies, the raids were often unsuccessful. As members of the local community, the police officers often had good relations with speakeasy proprietors. Some law enforcement agents were known to have a drink at local speakeasies, and sometimes notify owners of upcoming raids. If a raid was successful, the usual sentence for the proprietor was a few months in county jail and fines up to $500. Small fines did little to discourage people from repeatedly breaking the law.

Repeal: The end of Prohibition.

President Herbert Hoover called Prohibition “a great social and economic experiment, noble in motive and far-reaching in purpose.” However, instead of reducing crime, Prohibition increased it. In their selling of alcohol, gangsters set up nationwide networks. There was a general disrespect for the law, even among previously law-abiding citizens. During the 1930s, it became clear that Prohibition had failed to stop alcohol consumption. Additionally, as the Great Depression progressed, officials saw economic reasons to end Prohibition. A legal flow of liquor could be taxed. As he campaigned to be President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt announced that it was “time to correct the ‘stupendous blunder’ that was Prohibition.”

Repealing the 18th Amendment, the 21st Amendment was ratified on November 7, 1933, and Prohibition officially ended on December 5, 1933. Locally, the repeal of Prohibition was marked by parties including the Drunks Dinner at Filoli in Woodside. William and Agnes Bourn, the owners of Filoli, “being sober” and infirm, did not attend, but Ida Bourn hosted the festivities for 20 prominent guests. Not everyone was happy about repeal. Earning $10,000 a week as a bootlegger, G. William Puccinelli of San Mateo called Prohibition “the greatest law that ever was.”

Get Your History Fix

A more detailed account of Prohibition on the Peninsula can be found in the Winter 2011 edition of La Peninsula at historysmc.org/la-peninsula. To dig deeper into SF Peninsula history, visit historysmc.org