Words by Sheryl Nonnenberg

Strolling Stanford’s tranquil green campus, you might find yourself face to face with the hulking Gates of Hell. It’s hard not to halt before the morbidly fascinating bronze doors that represent sculptor Auguste Rodin’s crowning achievement. Inspired by Dante’s Inferno, the artwork’s roiling bodies seem to be attempting escape, doing their very best to twist free of their apocalyptic fate.

Stanford University is home to a world-renowned collection of public art sited all around the campus. To see all, or even a portion of it, requires a map and your best walking shoes. For an intimate encounter, head to the Rodin Sculpture Garden outside the Cantor Arts Center, which boasts the largest collection of Rodin sculptures in an American museum. Since 1985, this one-acre garden has been open to the public 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Visitors are welcome to wander around on their own, but to get a more in-depth perspective on the artist, how he worked and his importance in art history, an hour-long docent tour is offered on Friday and Saturday mornings.

On a recent sunny Saturday, Lisa Fremont prepares to lead a group into the garden. Lisa explains that she has been a museum docent for 23 years and is one of about 20 volunteers extensively trained in the art of Rodin. Her tour begins outside the museum’s main doors, overlooking the large marble sculpture of Menander, a Greek dramatist. Rodin, she says, rejected almost every prevailing principle in making this statue, preferring to celebrate the common man rather than take the staid, classical approach that idealized the figure. Rodin was also a master at capturing both movement and emotion, which soon becomes apparent as we enter the garden.

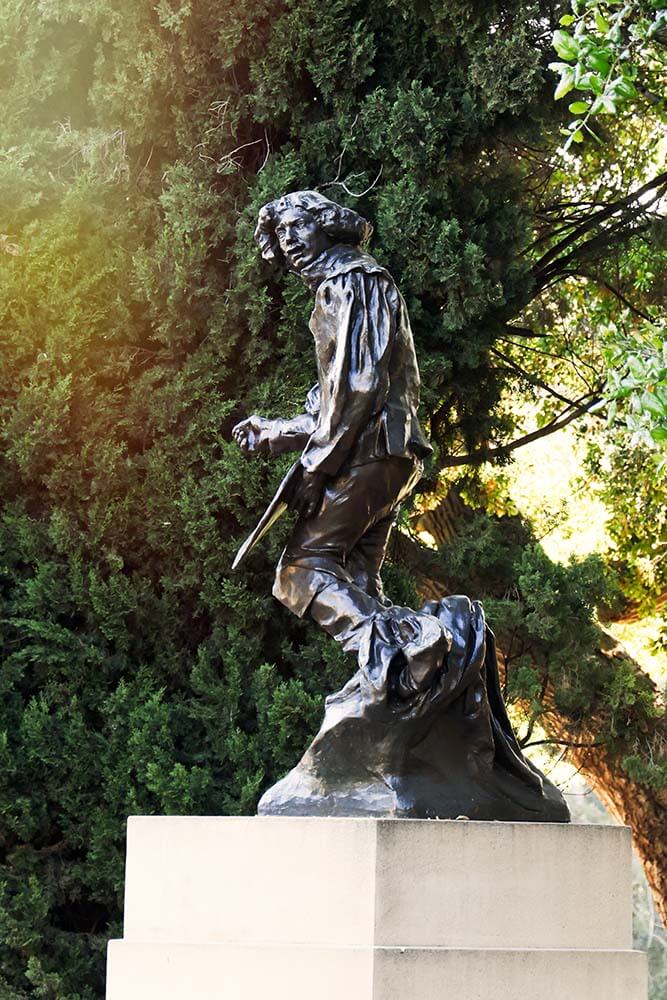

Twenty sculptures sit in residence here—some pose on pedestals; others are positioned directly on the gravel paths. Composed of bronze, the sculptures can be viewed in the round and, unlike the usual museum experience, visitors are welcome to touch the artwork. Lisa shares that Rodin worked mainly in clay and plaster, and that bronze casting, because of its enormous expense, was not utilized unless the artist had received a commission. He worked from live models, usually nude, and his forte was capturing a sense of drama. This “groundbreaking engagement with the body” is displayed in Martyr, a prone figure, seeming to writhe in pain. Lisa notes that the figure appears to defy gravity, with limbs in impossible positions. “Rodin was very much influenced by Michelangelo,” she notes, adding, “Big hands and big feet are often a clue that it is a Rodin.”

Another tell-tale sign is the way Rodin handled the surface, or skin, of his work. Unlike most artists who would strive for a completely smooth surface, Rodin preferred a “lumpy/bumpy” effect because uneven, raised areas catch the light. In addition, Rodin allowed the seams joining the metal to remain visible, another way the artist rejected the previously prescribed notions of classical sculpture.

All of these techniques can be seen in the figures of Adam and Eve, which flank the largest piece in the garden, The Gates of Hell. (Many of the pieces displayed in the garden are enlargements of figures found in the Gates). Alongside its 180 individual figures reacting to the impending destruction of mankind can be found the oft-quoted line from Dante’s opus: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.”

“This was Rodin’s Noah’s ark,” asserts Lisa. “He worked on this for 20 years.” Originally intended to be actual working doors, like the baptistry doors in Florence, the artist made the decision to make it immoveable instead. It is a dramatic and imposing piece of art that could take hours to examine closely. Figures, male and female, young and old, react in horror to the tumult that will end in eternal damnation.

It’s impossible not to get caught up in the drama of the Gates and when a loud pinging noise erupts from the sculpture, everyone jumps. Lisa only smiles. “Don’t worry, no one is trying to get out from behind the doors,” she assures. “That is the sound of the bronze as it expands in the morning sun.”

One of the most frequently-asked questions that Lisa gets is, “Are these originals?” She explains that Rodin donated his entire body of work, papers and all reproduction rights to the French government in 1917, the year before his death. This allowed authorized casts to be made, which are considered authentic, but not one-of-a-kind. Stanford’s extensive collection was gifted by collectors B. Gerald and Iris Cantor, who also donated funding to restore the museum (formerly known as the Stanford Museum) following the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989.

In addition to being a prestigious collection for the university, the sculpture garden allows visitors easy access to interact with art in an outside setting. For anyone desiring an even deeper dive, the galleries within hold detailed information on how the sculptures were created, along with many more of the 200 Rodin works owned by Stanford. Cantor Arts Center director Veronica Roberts notes, “Rodin was constantly questioning and reinventing the stakes of sculpture and its conventions: What happens when you play with the scale of the work? What does a pedestal do? And how does all of this unfold for a mobile viewer in the open air? The garden provides the space for visitors to find their own answers to these questions, not least a lush respite from the bustle of campus life.”

On this morning, people sit on benches reading the paper and enjoying their coffee, while others push strollers. Children flit from sculpture to sculpture, clearly delighted that no one is telling them not to touch. Signage directs interested visitors to the nearby museum rotunda where an enlarged version of another one of Rodin’s best-known works, The Thinker, resides. Rodin himself captured the allure of this erudite figure best: “What makes my Thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes.”

The Rodin Sculpture Garden may be one of the best-kept secrets on the Peninsula, but for Veronica, it is a source of joy each day. “The best thing about my office is the view of the Rodin Sculpture Garden and terrace café,” she says. “It provides a constant soundtrack of people gathering and I love watching visitors wandering through the sculptures. One of the many things I love about the Stanford campus is the incredible public art here and, for me, the Rodin Sculpture Garden is the mother ship!”

Plan a Visit Tours of the Rodin Sculpture Garden are offered on Fridays and Saturdays at 11:30AM. Visitors must obtain a free reservation pass to enter the museum. Sign up for a tour in the lobby. museum.stanford.edu