For over four decades, artist Robert Buelteman has led an enviable life as a working photographer, busily crafting images in his home studio tucked into a pocket of awe-inspiring beauty on the coast. There, he makes subjects of the area’s wondrous blooms, flora often plucked from his own backyard. And when inspiration strikes, he and his fellow artist wife Julie cruise the West in their VW van, ever-immersed in and inspired by its magical scenery.

“I feel that my job is to nurture a public appreciation of the natural world, no more, no less,” says Robert, “to provide artwork that makes people stop in their day-to-day busy-ness, to make the force of nature, the wonder of nature, present, like it is to me.”

His connection to nature began right here, starting with his idyllic childhood in a storybook Woodside before they built Highway 280. Raised by a World War II vet father who became a Pan Am pilot and an artistic mother, Robert reigned as the kindergarten King of the PTA May Day parade, bagged groceries at Roberts Market and wandered the still-gravel roads surrounded by sighing tree groves and unobstructed views of the Bay.

“I rest in the knowledge that the San Francisco Peninsula is my home,” declares Robert. “It’s where I belong.”

Robert’s love of nature followed him to college in the mountains of Boulder, Colorado, where he first picked up a camera in 1972. “The first truly spiritual experience of my life was seeing the world through that old camera,” he recalls. “The question was, how do I learn this craft? And how can I pay my rent with it?”

He remembers that at the time, in the post flower-child era, the art classes were all full of kids who were bent on self-expression and determined to become Great Artists. The problem was, Robert couldn’t get into any of the classes. So, he studied all of the technology behind photography. He studied physics to learn how light works, he studied chemistry to learn the chemical role in the photographic process and added in poetry and humanities for depth. Still, with a growing itch to get started, he left school and returned to the Bay Area, where he initially planned to finish college but instead secured a full-time position in a San Francisco photography studio and never looked back.

For years, Robert was successfully employed by Fortune 500 companies while he built his fine art landscape practice. He got married, started a family and worked hard until a turning point changed his life: his pleas to the San Francisco water department were finally answered, allowing him special access to the Crystal Springs Watershed. Ten years and 10,000 snaps later, his breathtaking photographic survey of its hidden wonders, The Unseen Peninsula, was published in 1994, enabling him to quit doing commercial work and focus on his fine art photography full-time.

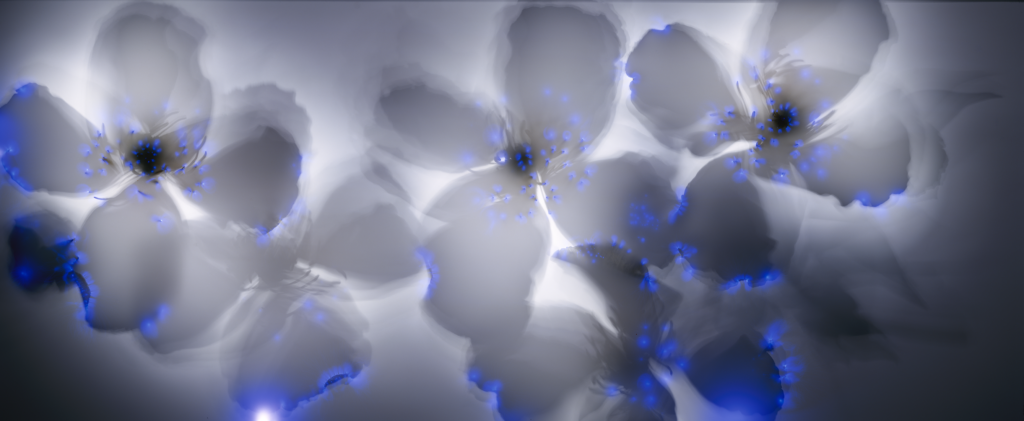

For years after that, black and white landscape work was his subject of choice. Robert made photographs that he thought really captured the great elements of living: earth, air, water, life, death, the passage of time, only to have someone look at them and say, “Where did you take that picture?” It really frustrated him because he wanted to make art that forced people into a deeper reflection, a deeper understanding of what he was presenting. He endeavored to create a Rorschach photo, an abstraction, rather than ‘a picture of a something.’ So after three books and feeling thwarted in that regard, Robert circled back to an earlier idea: What if he gave up the tools of photography as they were being used and tried something different?

An analog man in an increasingly digital world, Robert viewed the advent of digital photography as a means to capture ever-increasing levels of faithfulness in the resulting photograph. Yet he believed those same tools had become a hindrance because the images they created were so real. Where was the deeper expression of nature emanating from the soul of the artist?

“That’s what gave rise to my choosing to give up cameras, lenses, computers and also black and white film, to see how I might wrangle nature in a different way,” relates Robert. “I moved away from the landscape tradition to explore the idea of what is a photo, what is my role as a photographer.”

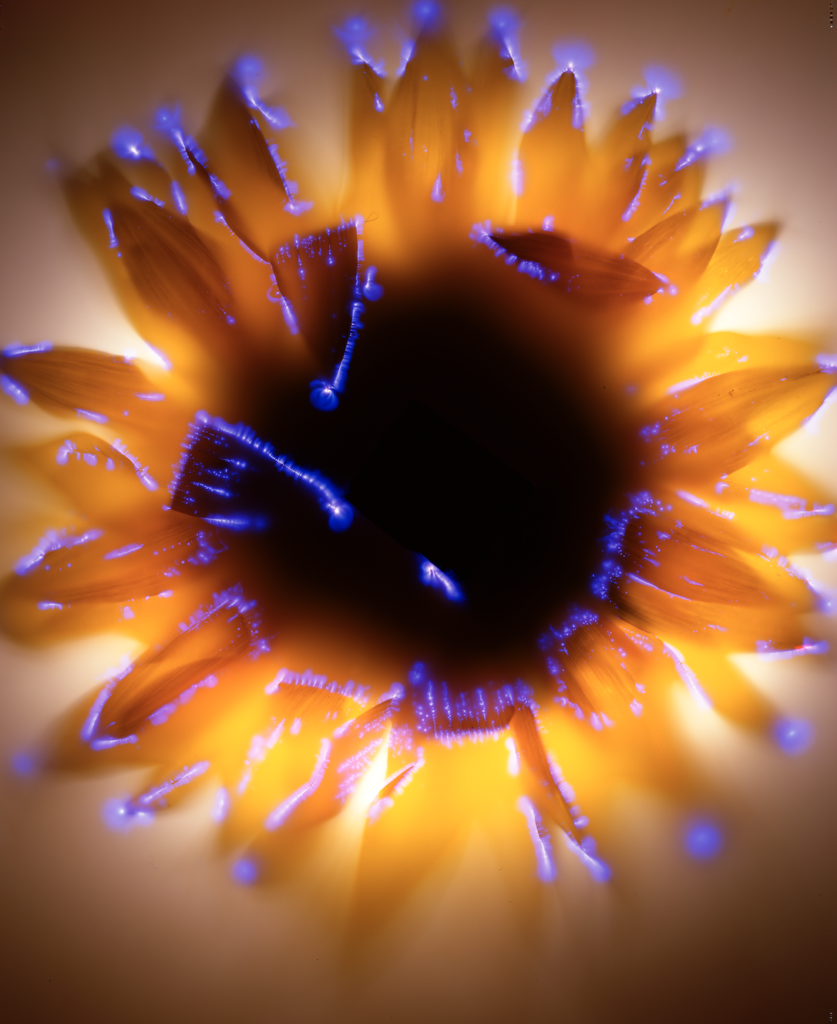

To answer that question, Robert circled back to a method first shared with him by his friend Sarah Adams, Ansel Adams’ granddaughter, who had introduced him to the work of the late Valentina and Semyon Kirlian. According to Robert, Kirlian and Valentina were devout Russian spiritualists who believed in crystal balls and were convinced that auras surrounded all living things. They’d observed a patient who was receiving medical treatment from a high-frequency electrical generator and noticed that when electrodes were brought near the patient’s skin, there was a glow similar to that of a neon discharge tube.

The duo began conducting experiments and in 1939 developed Kirlian photography. They found that if photographic film was placed on top of a conducting plate, and a conductor was attached to a hand, a leaf or other plant material and the conductors were energized by a high-frequency, high-voltage power source, the resulting photographs would show a silhouette of the object surrounded by an aura of light.

Robert was hooked. In 1999, he began building equipment and doing tests to use electrical charges on living plants illuminated by fiber optics, something he’d used to paint with light in his commercial work.

“I created this wild, colorful fantasy of the beauty and power of nature,” effuses Robert. And as far as he knows, he is the only one still doing this kind of photography—which he refers to as energetic photograms—creating his photos by hand and making his own prints, with no digital enhancements and no retouching. “They quit making the film I use in 2008,” he laments. “I have a stash I’m working with but I stopped seeing it for sale about three to four years ago.”

With all the twists and turns his career has taken and all his evident energy, it’s a surprise to learn that Robert lives with Lyme disease and at one time was unable to tend his garden muse.

“Lyme is a structural part of my life. I spend 14-16 hours a day in bed,” he shares. “The reason I am public about it is because the culture diminishes people who are chronically ill and I want to change the stereotypes about disabled people.” Robert points out that one in ten ticks carry Lyme. “And yes, you can catch it here,” he says. “The truth is that everyone has a disability, everybody has something. And my goal is really to stand for my art and to do so as a person who has faced a terrible illness.”

The success of Robert’s art stands for itself. He has 63 pieces of art hanging between 280 and Alameda de Las Pulgas on Sand Hill Road. His current work is focused on cyanotypes and he just wrapped up an exhibition at Art Ventures Gallery in Menlo Park. Next up, Jackson Hole. After that, he says, “I’ll try to figure out what the world wants from me.”