Words by Sheri Baer

On a fog-shrouded morning at Palo Alto’s Baylands Nature Preserve, a mockingbird perches on a toyon bush, eyeing the vibrant red berries. Black-crowned night herons nestle into the tall shoreline grasses while side-by-side flocks of American avocets and dowitchers create a light and dark patchwork pattern in the water.

“There’s a shorebird palooza and duck-a-rama going on here,” exclaims John (who goes by Jack) Muir Laws, as he greets a small group toting backpacks, spotting scopes and binoculars. “Get ready to get your nature geek on!”

Bird watching would be the default assumption, and yes, that will happen here. But the agenda of this gathering is nature journaling, a hobby turned movement that’s flourishing—with Jack leading the charge.

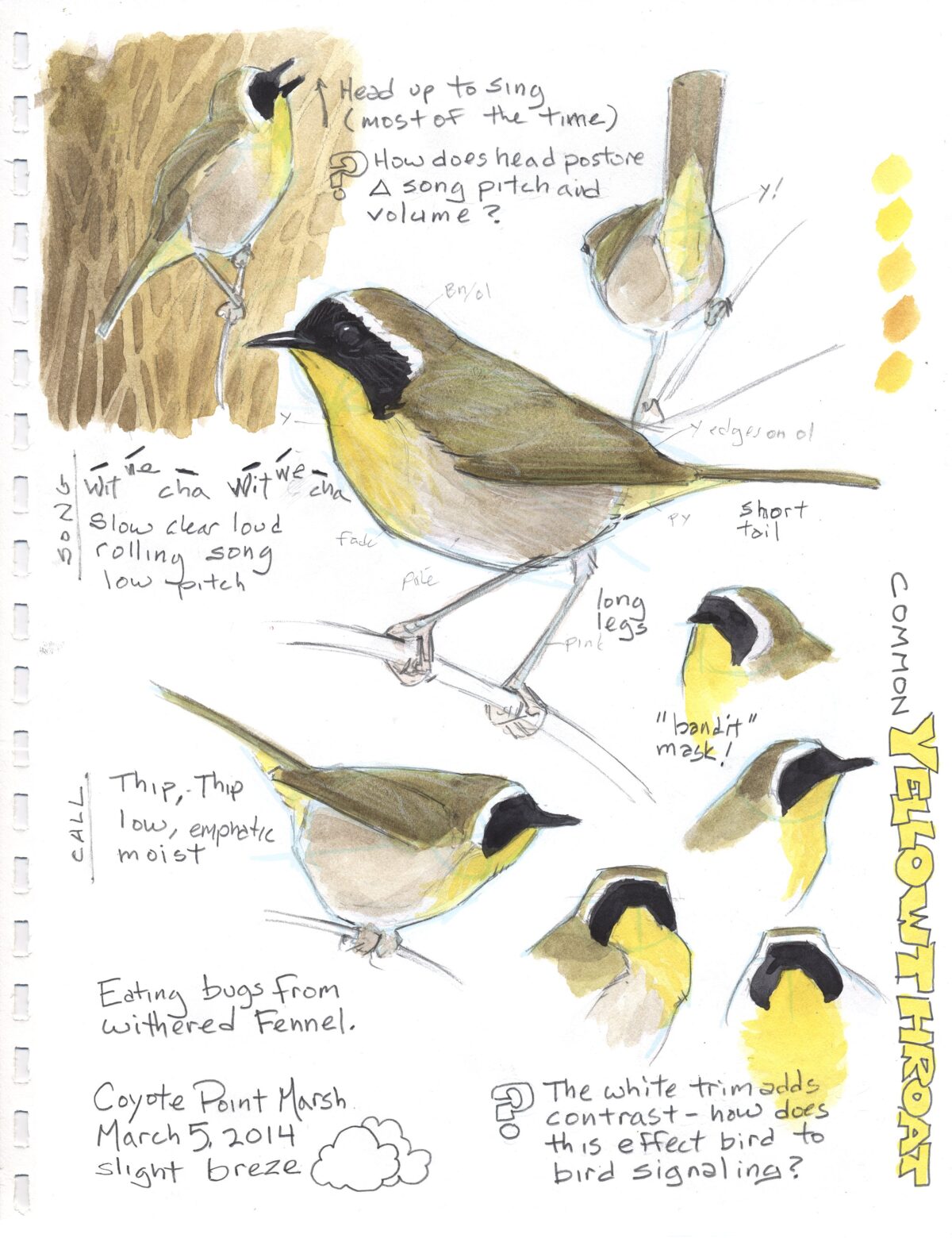

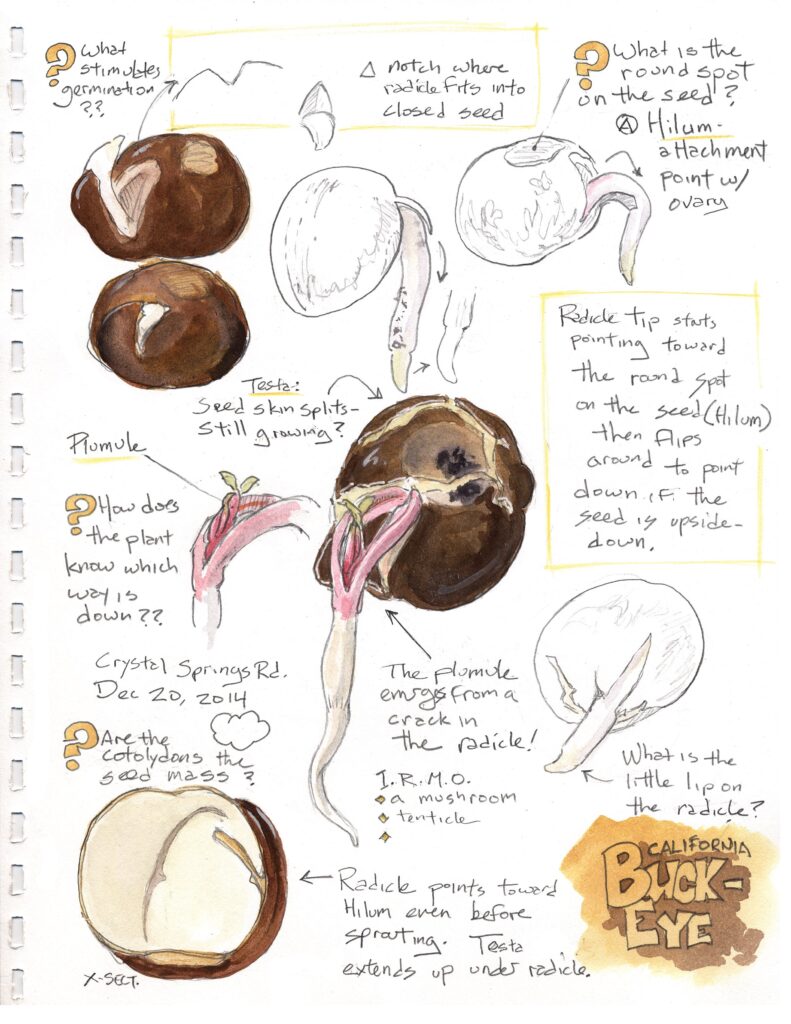

“A nature journal is a notebook in which we use words, pictures and numbers to describe natural phenomena that we encounter,” he explains, as workshop participants settle in around him, unpacking sets of drawing pencils and paints. “It’s a way to engage with our observations, our curiosity and questions and make connections to other things that we’ve seen.”

Jack pulls out a small white board and deftly sketches loose lines with a blue marker. “On shorebirds, it’s really helpful to squint your eyes and go for general values of light and dark,” he demonstrates with quick strokes. After a short, interactive tutorial, it’s time for individual exploration and study with a plan to regroup and share discoveries. “Decide what’s interesting to you,” Jack emphasizes. “Let your curiosity determine your focus.”

And indeed, the act of chasing his own curiosity is what set Jack on this unique path that he’s chosen to walk—accompanied by the likes of long-eared chipmunks, spotted towhees and shasta blue butterflies, and an impassioned community of nature journalers.

With a given name of John Muir, it might seem like Jack was predestined to align his journey with the natural world. The question can’t help but pop to mind: “Are you related…?” No, Jack says, he’s not a direct descendent of the famed naturalist. “That’s what my mom and dad named me,” he relays, explaining that John was a nod to his maternal grandfather and Muir his paternal great-grandmother. “But I strongly suspect that that had a role in me becoming a person fascinated with natural history and conservation in California,” he concedes.

Although Jack dons a blue wool cap to ward off the morning chill, much like his legendary role model, he’s the wearer of many hats including naturalist, educator, artist and author. The numerous publications written and illustrated by John Muir Laws include The Laws Field Guide to the Sierra Nevada, The Laws Guide to Drawing Birds and The Laws Guide to Nature Drawing and Journaling. Jack doesn’t hesitate when asked to synthesize the common thread in his work: “My goal is to help people fall in love with the natural world to the point that they step forward to become stewards to protect it.”

Given that fostering love is a tall order, Jack concluded that he needed to clearly define it first. Reflecting on the relationships in his life helped him pare it down. “I believe that love is the act of sustained, compassionate attention,” he summarizes. “If I am teaching people how to pay attention, I am teaching people how to fall more deeply in love with the world.”

And that’s where the nature journal comes in. “The journal is the tool that unlocks the door,” he explains. “It’s the key.”

Jack credits his family with guiding him to that key—and ultimately the calling that he now shares with others. Both of his parents relished nature and natural history (his mother leaning toward botany and his father toward birding), and growing up in San Francisco, Jack turned Sutro Forest into his own personal jungle to explore.

On a botany field trip organized by his mother, 7-year-old Jack observed one of his mother’s friends sketching the flowers that she saw in a notebook. “I was absolutely fascinated,” he recalls, “so anywhere Neela would go, I would sit down next to her and watch.” Before the next family adventure, Jack’s mother presented him with his own notebook journal and supplies. “She noticed exactly where my focus was,” he reflects, “and met me at that spot to help me take the next step.” Jack’s grandmother also played a pivotal role by giving him his first watercolor set and lessons in art. “Don’t worry about making it perfect,” she told him. “Have fun with it.”

He cites another formative moment that happened on a birding trip in Point Reyes. Jack watched in wonder as his father quietly approached a willow bush. “He began to make this ‘pishing’ noise with his lips—‘pish, pish, pish, pish’—and this tiny bird started to dance closer and closer to us,” he recounts. “My dad was Dr. Doolittle! He was speaking to the birds.”

Jack’s father pulled out a field guide, and together they determined that the olive-greenish bird was a ruby-crowned kinglet. “Once you’re hooked on the birds, everything else kind of comes from that,” he says. “I discovered that these field guides were like little troves of treasures that you could go out and find—every walk became a treasure hunt.”

Diagnosed at a young age with dyslexia, Jack struggled in high school but always found respite in nature. For one of his classes, he loaded his backpack up with hefty field guides to hike the John Muir Trail. With the additional support of influential biology and history teachers who encouraged his scientific curiosity, Jack found his way to UC Berkeley where he pursued a major based on natural history and environmental education.

Throughout his academic studies, teaching roles and the career that followed at the California Academy of Sciences, Jack continued to draw and keep journals of all his adventures and discoveries. While working at an outdoor education program in Marin, his journaling drew the attention of students, who began to use their free time to join him. Jack witnessed this outlet—so familiar and ingrained in him—resulting in a transformative experience. “Teaching somebody facts is proverbially giving somebody a fish,” he realized, “but when you teach them how to observe, how to ask questions, how to wonder, how to nature journal, you’re teaching them how to fish.”

Another watershed event came as Jack sat with his grandmother, just before she passed away. Pondering what he would regret not doing in his own lifetime, he reached two conclusions: he wanted to have a family and be a father and also to create a field guide to the Sierra Nevada, a definitive guide that he wished had existed when he hiked the John Muir Trail.

Jack left his job at the Academy of Sciences to study scientific illustration at UC Santa Cruz and then spent the next six years meticulously documenting all the natural treasures between Yosemite and Mount Whitney. “During the spring, summer and fall, I’d be hiking in the Sierra Nevada with the backpack on and a notebook, stopping at every plant—sit down, key it out, make a painting, move on to the next,” he says. “Paint, paint, paint, until I’d run out of paper and run out of food. I’d resupply and then do it again.”

Published by Berkeley’s Heyday Books in 2007, The Laws Field Guide to the Sierra Nevada was released to rapturous reviews. As additional publications followed, Jack realized his other life goal when he met his wife, Cybele Renault, an infectious disease specialist. About 10 years ago, they settled in San Mateo to raise their two daughters. Referring to themselves as “The Adventure Girls,” Amelia and Carolyn are always readily equipped with shoulder bags packed with their nature journals and field supplies.

A decade after moving to the Peninsula, Jack continues to be awed by the natural bounty surrounding his family. “When you look at the corridors of wildlife habitat we have here, we are living in an absolutely amazing place,” he notes. “The bay is lined with these incredible bird magnets and then we’ve got our coastal range hills with so much protected and preserved open space.”

The Peninsula now provides daily inspiration for Jack’s primary focus, which is getting the tools for nature journaling into the hands of as many people as possible. At his website johnmuirlaws.com, the tagline reads, “Nature Stewardship Through Science, Education and Art,” and the offerings there provide a vital hub for a rapidly-growing community. Free online lessons. Events and workshops. Nature journal clubs. Educator resources. A naturalist store—with Jack’s field guides and books, along with art supplies. “There’s no paywall, so all of my classes are available for anybody, anywhere, at any time,” Jack says. “Taking a class gives you some structure and regular practice, and once it becomes a routine, it gets a lot easier.”

Acknowledging that it can be intimidating to get started, Jack provides quick assurance that you don’t have to be an artist, writer or scientist to enjoy nature journaling—the goal is to notice things, to pay attention: “If you make an observation that you otherwise wouldn’t have made or you ask a question that wouldn’t have occurred to you, your journal page is successful, no matter how it looks.”

That being said, Jack also believes that drawing isn’t a gift but a skill that can be learned at any age. “You will become an artist if you just start doing it on a regular basis,” he asserts. “The skills actually develop surprisingly fast.” And how will you know what to focus on? Jack suggests giving yourself a specific search pattern. “What you’re looking for initially is two things: wonder and beauty,” he says. “Look for micro-beauties like a leaf or the way the sunlight hits moss and then be on the lookout for the little mini-mysteries—phenomena and events—that you don’t fully understand.”

Although recognized as a leading advocate for nature journaling, Jack knows he can’t drive the movement alone. That’s why he has worked closely with numerous teachers, homeschool groups and environmental educators across the U.S. for more than 30 years to jumpstart nature journaling programs. “This is such a useful skill that we need to teach the teachers and share this skillset more broadly,” he explains.

To accomplish that, Jack makes resources such as the curriculum Opening the World through Nature Journaling and the comprehensive guide How to Teach Nature Journaling (co-authored with Emilie Lygren) available as free downloads from his website. How does he make a living when he provides so much au gratis? He credits the nature journaling community—those who can afford to do so—with supporting his work through donations. “People have been really generous,” he says appreciatively, “and that then allows me to turn around and be really generous too.”

Currently offering three online classes a week—along with an ever-increasing number of nature journal video tutorials—Jack looks forward to returning to regular workshops in the field. As the sun pushes through the morning fog during the recent outing to the Palo Alto Baylands, the gratitude among the attendees is palpable. Brian shares that he’s been journaling since 2019. “I wanted to learn to draw,” he recalls, “and if you type in ‘draw,’ Jack’s name comes up pretty quickly.” Amy, who bought her first notebook in 2016, nods with a smile: “I thought I could find hope in beauty and nature.” High school senior Fiona chimes in with her take. “I love asking questions,” she says. “I’m big on curiosity.” Heather agrees, adding, “There’s something about nature that makes us better people.”

As Jack tracks the burgeoning number of nature journalers—and the passionate engagement he sees—he’s continually reinforced in his mission. “There’s always something to be curious about if we choose to be curious,” he reflects. “Fundamentally, we’re teaching people how to fall in love with the world and how to celebrate their own capacity for learning and growth.”