The question “why here” comes up a lot when looking at the history of the Peninsula. Why did one of California’s richest men establish a school here, 3,000 miles away from all of the other prestigious universities of the era? How did this one tiny area become the world’s center of innovation? A hundred years ago, this area was also chosen to be the site for something unique and impactful—an Army training camp.

Although the Second World War tends to overshadow the first in terms of American knowledge and imagination, for the Peninsula, the First World War was a remarkably influential time. When the United States became involved in the war, it was immediately clear that the American military was in no shape to ship over to Europe. That meant that the Army needed to mobilize troops as fast as it could, which required building places to train the troops before they shipped overseas. Bases began to pop up all across the country, but the biggest one west of the Mississippi was here. Camp Fremont extended from San Carlos to Los Altos, centered in what is today Menlo Park. If you’re a longtime Peninsula resident and the name “Camp Fremont” doesn’t ring a bell it’s not surprising, since the camp existed only for 18 months and once the war was over it disappeared almost as fast as it had sprung up in the countryside of Menlo Park. The short, strange life of Camp Fremont is not just an entertaining piece of local history, but also one of the many small pieces that begins to explain why so many fascinating things happened here.

Another reason Americans might pay less attention to the history of World War I is that the conflict was largely absent from many Americans’ lives. For three years after the war broke out in Europe, the country was conflicted about the idea of entering a global conflict that seemed so far away. But after the sinking of the submarine Lusitania in 1915, and the death of American civilians who were on board, America gradually drew closer to involvement, officially entering the war on April 6, 1917. War made it to Menlo Park a few months later, as ground was broken for Camp Fremont on July 12 of that same year. Menlo Park had all of the qualities the Army was looking for in a training camp: warm mild, weather (they hoped to save money by quartering most troops in tents rather than permanent buildings), easy access to the railways and countryside that was similar to the French hills where the troops expected to be fighting.

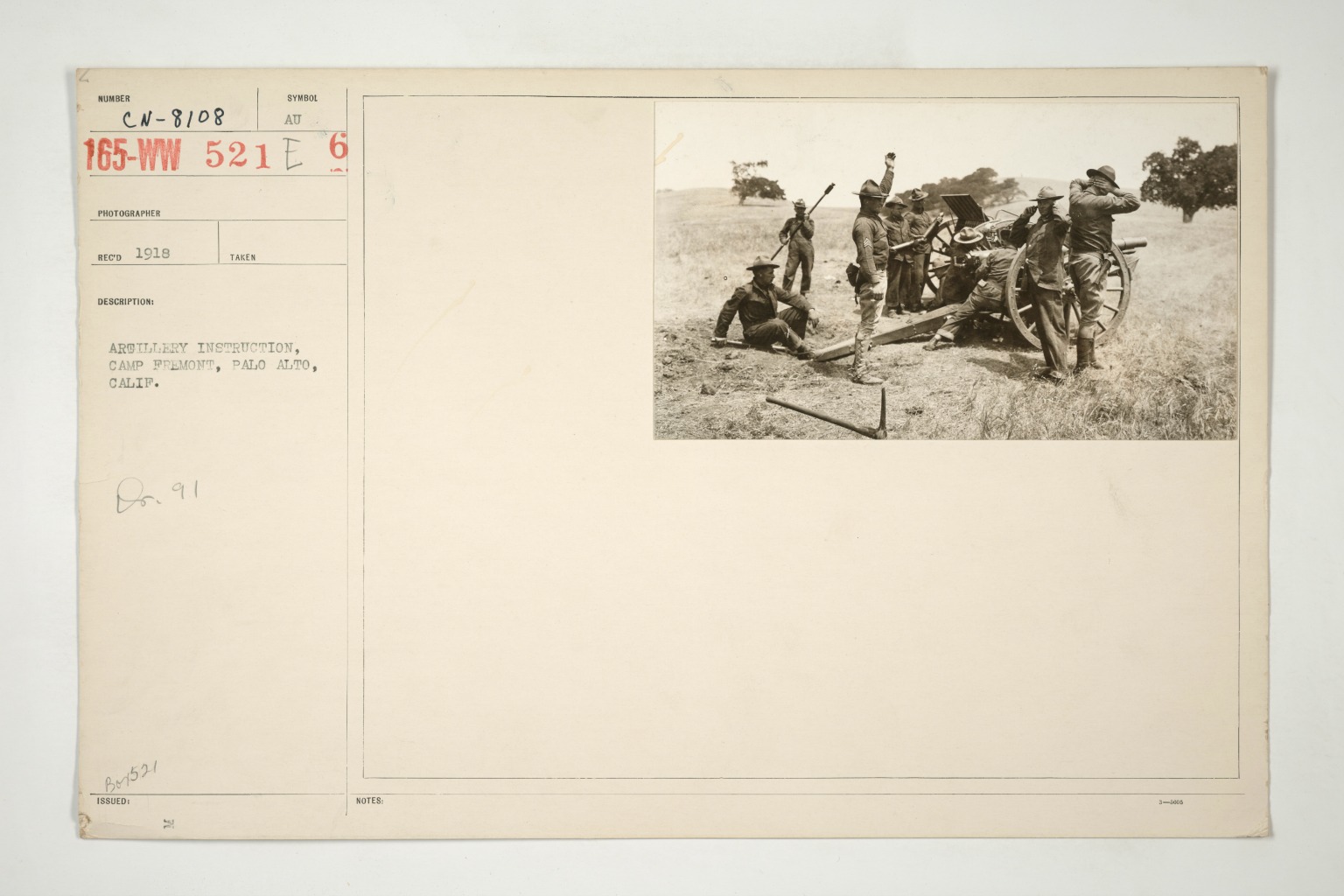

At its peak nearly 27,000 personnel occupied the base, and 43,000 soldiers passed through Camp Fremont before the war was over. For context, Menlo Park was home to only 2,300 people the year before. Besides both ground and mounted troops, Camp Fremont was home to more 10,000 horses and mules. Before the hills rang out with sounds of artillery practice, there was a symphony of hammers. Anyone with carpentry skills on Peninsula was drafted into the effort, and by the end of the project it took 700 men to break 100 railroad cars into lumber for temporary buildings.

Barracks consisted of wooden floors and side walls, topped with tent-like canvas. In order to facilitate movement between the camp and other Army bases like San Francisco’s Presidio, Southern Pacific workers laid additional track from the main rail line to the middle of camp. El Camino Real was paved to accommodate the increased traffic, and Menlo Park gained a reputation as one of the worst traffic bottlenecks on the Peninsula.

Suddenly every available storefront in Menlo Park was occupied by merchants from throughout the Bay Area. A movie theater, post office, church and library all sprung up around the camp. Beltramo’s Winery and every tavern within five miles of the base were declared dry by order of the army and the county. Sequoia High School opened a branch on the base offering classes in English, arithmetic, shorthand, typing and accounting.

Shortly after the building started, the war department halted the effort for three months, largely due to disagreements with landowners about infrastructure the Army had planned to include as part of the camp. The original troops who had expected to live at Camp Fremont were moved east at one point, but then the 8th Division, Regular Army was transferred in and remained until the dismantling. The troops that had trained in Menlo Park to join the war efforts in France never did reach Europe. Some 5,000, however, did serve time in Siberia. Yes, Siberia. Although it’s mostly forgotten, one of the last elements of World War I was the launching of the American Expeditionary Force to Russia at the end of the Russian civil war. President Woodrow Wilson sent the troops there in a failed attempt to protect supply routes and keep an eye on the new Bolshevik regime, and a number of Camp Fremont men were caught up in the ill-fated mission.

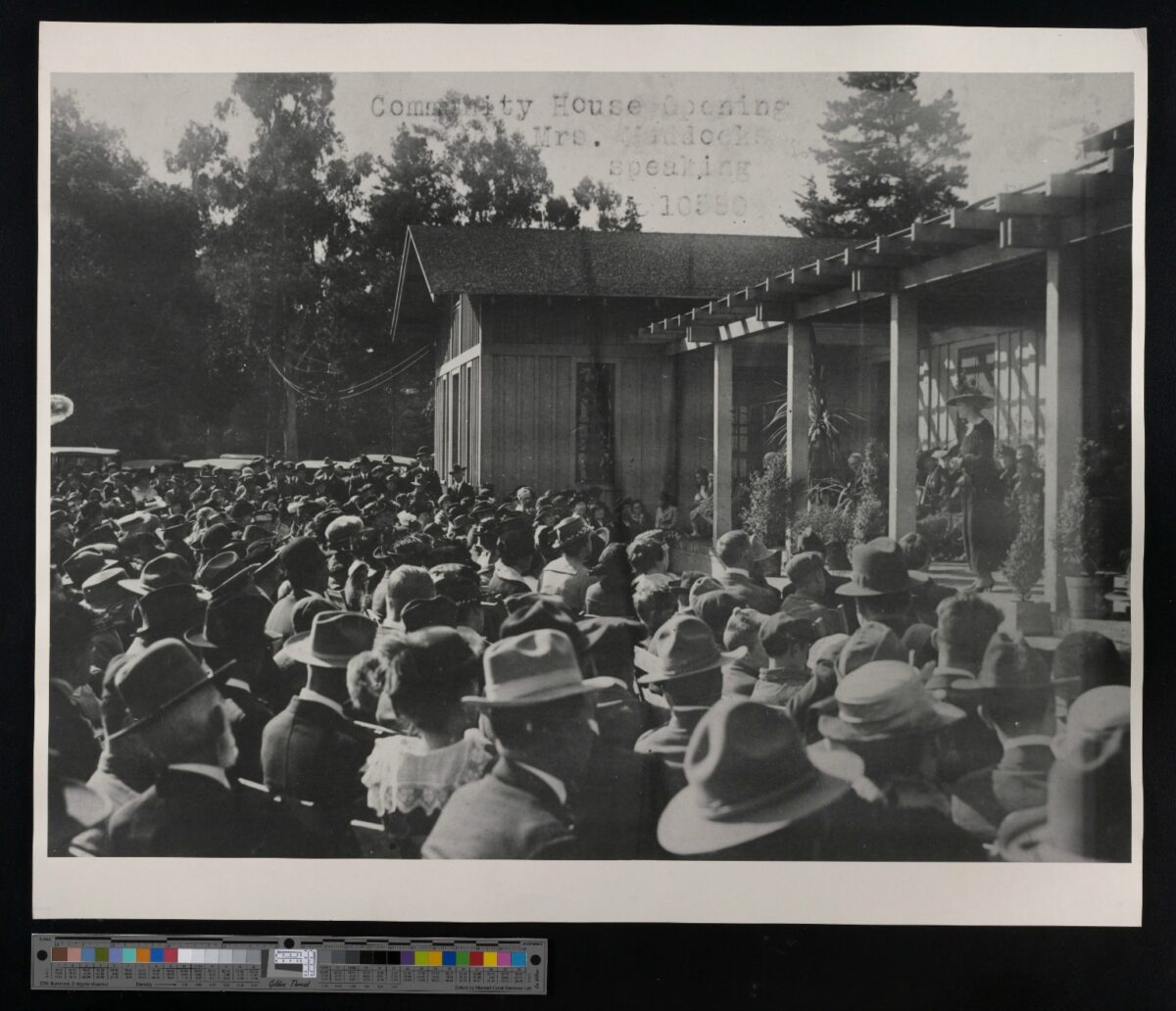

Before it was ordered closed in December 1918, just one month after the armistice was signed, 43,000 men had been trained. So, just 18 months after it was erected, Camp Fremont was abandoned and the land reverted to its previous owners. Since so many of Camp Fremont’s buildings were designed to be temporary, very few of them are left. The building that used to house the Oasis Beer Garden on El Camino is one example. MacArthur Park in Palo Alto is located in a former Camp Fremont building, the YMCA Hostess House. The building was designed by Julia Morgan, who would go on to be the architect for Hearst Castle. The Hostess House was moved the year after the camp closed from its original location in Menlo Park to its current home near the Palo Alto train station. Before becoming a restaurant in 1981, the building was also one of the first municipally-owned community centers in the country.

The rest of Camp Fremont’s legacy is harder to see. Due to the efforts of the 8th Army Corp of Engineers, the once rustic town of Menlo Park had paved roads, water and gas services by the time the camp closed. The engineers also left a legacy of tunnels in the Stanford foothills, used for artillery practice and to prepare men for the trenches they planned to fight from on the Western Front. Some longtime Peninsula residents recall playing in the tunnels before Stanford sealed them in the 1940s, and they’ve also occasionally made a sudden appearance during rainstorms when they become sinkholes.

Local construction workers certainly can’t forget that the area once was home to an army camp, since they keep finding artillery shells buried underground. Combing through local newspapers, it’s clear that this is a story that repeats itself every few years: a strange metal object turns up in the foundation of a new home or in a park, and then someone does a bit of historical research. Residents seem to be continually surprised that an unexploded bomb could have survived for over a hundred years, but the experts who are called out to deal with the explosives (usually the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office bomb-disposal team, sometimes with the help of military experts from Travis Air Force Base) must be used to it by now.

There are also some intriguing ways in which Camp Fremont echoes the Peninsula of today. Many of the American troops quartered in Menlo Park had in fact been born in another country. Just as talented people from all over the world move here to work in high tech or venture capital, thousands of recent emigres ended up at Camp Fremont in the service of their new home. After the war, many of those soldiers took advantage of the fact that Congress passed legislation allowing for the expedited naturalization of foreign-born members of the military. In all, nearly 3,200 men became United States citizens before the base closed.

Though Menlo Park will probably never become a tourist destination for military history buffs, there’s a small but strong group of Peninsula residents who are determined to tell the story of Camp Fremont. Chief among them is Menlo Park local historian Barbara Wilcox. She’s the author of the authoritative book on Camp Fremont, World War I Army Training by the San Francisco Bay. The book was awarded the Stanford Historical Society Prize for Excellence in Historical Writing and is recommended for anyone who wants to learn more about Camp Fremont. Local historical societies, particularly the Menlo Park Historical Society, are using the centennial of the war’s end as a way to drum up interest among local residents. This month, the society will be holding a ceremony in Fremont Park on the corner of Santa Cruz Avenue and University. The event will hopefully feature some of the society’s original World War I artifacts, including a full-dress uniform. At the very least, this November 11 is a good time to look back and try to imagine the Peninsula of 1918. The area would be bustling, with people from all walks of life trying to work amongst each other without stepping on too many toes. The landscape would be dotted with tents and lean-tos rather than VC firms and tech offices, but the hills and coastline would still look breathtaking. Chiefly, there would be the same feeling in the air that exists in today’s Peninsula—the knowledge that something special is happening here.