Words by Sheryl Nonnenberg

It has been described as a “hidden gem” and an “oasis of calm in the midst of Silicon Valley.” It is The Foster, a 14,000-square-foot former industrial warehouse in Palo Alto that houses the work of just one artist, Tony Foster. But far from being a monographic museum, The Foster has a broader and very timely mission: “to inspire connection to art and the natural world.”

How the museum’s creator and staff have undertaken to achieve this lofty goal is a unique story and one that could only happen on the Peninsula, in the cradle of innovation. It is also a case study in how a nonprofit institution learned to pivot and adapt to the unexpected disruption caused by a worldwide pandemic.

The Foster is the brainchild of Jane Woodward, a lifelong Palo Alto resident and adjunct professor at Stanford University. Jane, a geologist, is also a founder of MAP Energy, an energy investment firm. During a visit to the Natural History Museum at the Smithsonian in the late 1980s, Jane first encountered a Tony Foster watercolor wilderness Journey—John Muir’s High Sierra. This led to her meeting Tony and she began to collect Foster’s artworks. Deciding that each of Foster’s Journeys, a series of artworks based on a wilderness theme, makes a more forceful statement when seen in its entirety, she embarked upon a plan to create a nonprofit museum to hold them intact and share them.

After acquiring Sacred Places: Watercolor Diaries from the American Southwest, Jane began to form The Foster in 2013, and the museum opened its doors to the public in 2016.

CAPTION: The Sacred Places gallery at The Foster in Palo Alto, CA. Photo by Eileen Howard. Courtesy of The Foster

Soon, school groups, senior groups, artists and naturalists were making appointments to visit and enjoy Tony Foster’s depictions of such far-flung places as Mount Everest, Costa Rica, Guyana, the Grand Canyon and the Andes. Educational programming that included lectures, art lessons and tours were in full swing, only to be curtailed by COVID in March of 2020. “Approximately 20,000 visitors came to the museum during the first four years,” notes co-director Anne Baxter. “We were rolling and building, so it was frustrating to have a seizure of all that programming.”

It was also a drastic change for the 75-year-old Tony Foster who, for 40 years, has been traveling the globe in order to create his watercolor diaries. A native of Cornwall, England, Foster started out as an art educator and Pop artist but soon discovered that his love of travel, passion for the environment and skills as a watercolorist could be combined. One of his first expeditions was to follow in the footsteps of Henry David Thoreau by walking and canoeing around the remote parts of New England. Interest in the resulting watercolors inspired him to continue his passion as an artist-explorer, and soon Foster had developed a network of fellow travelers, scientists and art collectors who wanted to help and sometimes join along. “Tony is charismatic and gregarious but also humble and kind,” observes Anne. “He has always attracted people who believe in him and support him.”

Fellow adventurers, whom Foster refers to as “companions,” do everything from arranging for equipment to setting up tents to making food for the group. Some are collectors who want to see and experience the landscapes Foster captures. Others are naturalists who just enjoy the challenge of living in the wild. For Foster, the objective is clear: “I have drawn my inspiration from the sublime beauty of the wilderness.”

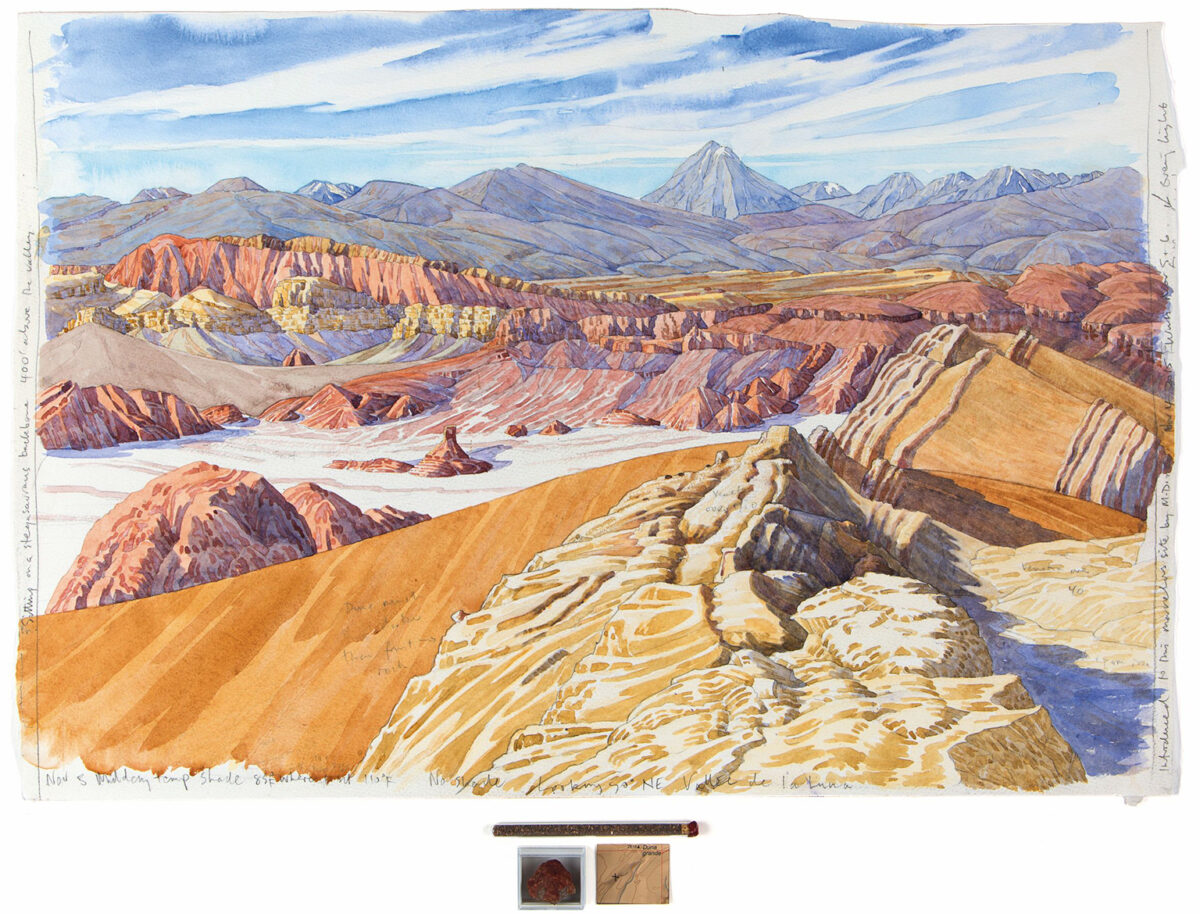

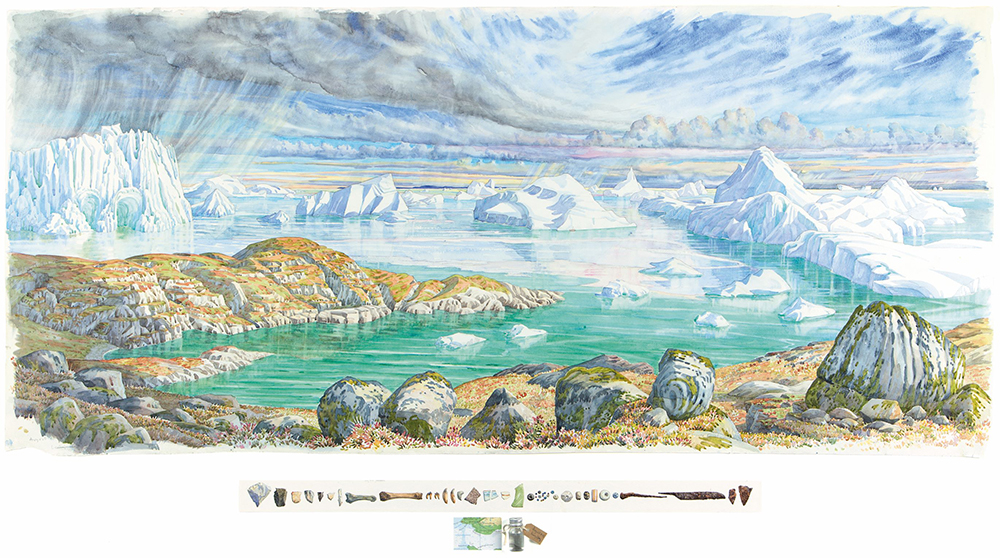

Once Foster has found the desired setting, he sets up his work space and paints for hours at a time. Watercolor, because it is quick-drying and very portable, is his medium of choice. He has worked in some of the most adverse conditions—rain, wind, snow and sleet, and has even sketched underwater (he is a longtime scuba diver). Foster often completes his work back in Cornwall but never refers to photographs. Instead, he relies upon his detailed diary entries and the various souvenirs that he might paint, be gifted or gather onsite. These could be leaves, rocks, feathers or pieces of bone. Oftentimes, these small objects will be placed at the bottom of his framed work. They serve as talismans and reminders of the fragile nature of these locations.

Told by a New York City gallerist that his work was unacceptable because it was “just too beautiful,” Foster has embraced his role as chronicler of places that are awe-inspiring and worthy of saving for future generations. A look at the catalog, Exploring Beauty, reveals the extraordinary range of his representational skills. The Atacama Desert in Chile is a study of brown and ochre hues, a rugged landscape devoid of human interaction. In France, Mont Blanc takes center stage, snow-covered and remote, while the foreground is dotted with spring flowers and green hills. Even the frigid landscape of Greenland is lovingly portrayed in pastel hues, while Foster’s diary explains, “worked from 8:00am to 11:30pm, frozen and exhausted.”

CAPTION: Tony Foster with painting in situ at Point Sublime, Grand Canyon. September 30, 2004. Photo by John Frazier. Courtesy of Foster Art & Wilderness Foundation.

“His art is really a story, from the time he tears off the first piece of paper to the final brushstroke,” notes co-director Eileen Howard. She shares that a trip to Green River as part of his next Journey had to be postponed due to the pandemic but that Foster has found inspiration close to home. “He reconnected with beauty in his own backyard,” she says, “creating a series of Lockdown Diaries.” Another earlier project, entitled A Year in the Life of a Cornish Hedge, captures the seasonal changes of a spot he passes by each day.

The Foster staff has kept busy since the museum’s closure. Anne explains that Jane suggested pivoting to online programming, continuing many of their art lessons and lectures. “Tony was resistant to Zoom at first,” she recalls, but soon he was participating in a series of interviews (“Conversations with Tony Foster”) that can be seen on the museum’s website. In addition, Eileen shares that the museum is overseeing a Journey Exhibition Archival Project, in which every aspect of Tony’s 17 Journeys is being documented. They work from the art and artifacts collected during each trip, interviews, maps and Tony’s diary notes. Consultation with Tony allows them to record the ‘where, how, who and why,’ along with the effects of each one. Says Anne, “People love Tony and we also share his mission of protecting wilderness areas. That is the bigger mission.”

The museum is currently accessible by appointment, and The Foster staff is in the process of planning how to more broadly reopen the museum to the public and to ramp up its programming. They are also open to renting the facility to organizations aligned with their environmental mission. But first, the public needs to find their way to this industrial district in south Palo Alto.

Museum manager Deb Waltimire, who recently joined the staff after a stint at the Disney Family Museum, acknowledges, “We are a hidden gem in a commercial area.” Anne agrees, adding, “So much thought has been given to the experience here, the colors, the lighting, the displays. It’s a lovely, engaging mood.”

The staff has considered other potential sites but ended up feeling that they are right where they belong. “You don’t have to travel the world, but if you want to, come to The Foster,” encourages Eileen.

And what will the long-term future hold for this art museum with a mission? Anne speaks with assurance that The Foster will continue to protect and share Tony Foster’s Journeys and message. “We are really committed to that,” she asserts.

As for Jane, whose passion for the environment and conservation converged with the peripatetic Journeys of a watercolorist from Cornwall to create a truly unique institution? She hopes, “That we become better known as a hidden jewel museum here in Palo Alto—a place of beautiful art and peaceful reflection.”