words by Silas Valentino

The Greenmeadow neighborhood in south Palo Alto is a swath of homogeneous Eichler homes, but on a quiet court in the middle of the subdivision is a garage unlike any other on the block.

Hoisting his garage door open, Tom Haines welcomes you inside his world. Neatly arranged without a square foot to spare are the machines he uses every day to breathe life into wood. There’s a belt sander, bandsaw, thickness sander, table saw and the focal point of his shop: a custom lathe.

This machine tool is crucial to Tom’s craft: woodturning, or the action of shaping wood with a lathe. The lathe rotates a piece of wood about an axis to cut, sand, knurl, drill and ultimately, turn a log of wood into a work of art. Tom picked up the lathe from the San Jose Union School District some 15 years ago and being the habitual tinkerer that he is, he upgraded the tool to include a monitor screen that allows for precise cutting. It’s Tom’s own way of peering behind the solid walls of wood.

The son of a carpenter and the father of a blacksmith, Tom has craftsmanship ingrained into his soul. He built his own furniture and sailed in boats made by hand all the while working a career in sales for Texas Instruments. Tom focused his attention to woodturning after a surprise gift from his children 20 years ago. Bowls of various sizes, chalices and even urns have swiftly emerged, each one turned and gorgeously designed in his home shop.

As the conversation turns, Tom pauses to consider how his artistry contrasts with his craft. He rarely creates the same design twice—always leaning in deeper and challenging himself to carve more intricate lines or celestial, engrossing patterns. One bowl might look like an abstract rib cage forming a basin while another evokes a sombrero hat with a smooth finish. He’s created original analog clocks and ornaments reminiscent of Muscovite Russian architecture—so why not identify as an artist?

“Is this art or is this craft—that’s the big question,” Tom muses. “I like to think that I want to be an artist but what I probably provide best is a craft. People want salad bowls and that’s something I can do for them. But on the other hand, I always want to do something different. And that’s where I think I become an artist.”

On a recent afternoon, as the winds of winter blew through the neighborhood of Eichlers, Tom was in his backyard and attempted to switch on his propane patio heater. However, the pilot flame would not light.

Although nestled in his 80s, Tom didn’t hesitate to take the heater apart and examine the device himself. Piece by piece. He discovered a plugged hole, possible gunk from accumulated gas, and attempted to coax it out. When it didn’t budge, he retreated to his shop to produce a drill set. Cutting into the detritus and ultimately clearing it out produced a warmer patio, but it also led Tom to reflect on the changing world he’s borne witness to over the years.

“This heater was made to sell, not to be maintained. Can you imagine spending $150 and then throwing it away after a season—that’s ridiculous,” he declares.

“I’m old enough to have lived through World War II, where you couldn’t buy new stuff. You had to use everything that you had. If you had an automobile with dents in it, you still drove it. You couldn’t buy new tires so there was a tire recap business in my hometown of Minneapolis. We now live in a throw-away society.”

Tom’s talk isn’t grouchy or irritable; rather it’s plainly optimistic. He speaks less to what our culture has become and more to the untapped opportunities to be crafty if only we decide to get our hands a little dirty or swing a hammer around.

Although given that Tom is essentially the product of an artist and a craftsman, he clearly had no choice in the matter.

Born during the Depression, Tom had an innate sense for imagination. His mother had a creative eye and designed the interior of their home while also painting in oils. His father worked as an executive for the building engineering company Honeywell with a midnight passion for woodworking.

In the basement of their Minneapolis home, Tom stood adjacent to his father as he hammered out furniture and cabinetry. Soon, Tom had his own miniature workbench outfitted with saws and his own hammer. (“I was pounding nails by age five,” he quips.) Together, the father and son duo built a desk of maple wood and Tom hasn’t stopped working with wood ever since.

When he was 11, he attended a summer camp on Lake Minnetonka in Minnesota where he met his first love: sailing. Tom built his first boat at age 16: a little rowboat dinghy made of Douglas fir plywood to allow him to paddle out to his sailboat.

He attended Cornell University to study mechanical engineering and finished his education as the captain of the sailing team. His first job was in thermal engineering in Syracuse, New York, where he designed air conditioners. During his free time, he made two sailing boats by the age of 24.

A career shift into sales took Tom to Dallas to work for Texas Instruments, just as the company launched its debut silicon transistors. In 1969, Tom arrived on the Peninsula after taking a sales position within the company in San Francisco. He remembers observing the psychedelic Sixties from afar; instead, Tom could be found at the Palo Alto Yacht Club. “I was focused on work and family,” he says of the time, raising a son and daughter. “I did buy a new boat called Faster Now, and then later another one named Titanic.” He laughs about the ominous boat name but becomes more serious when he divulges that he had to relinquish the Titanic two years ago.

“My first love was sailing but I had to let it go because of age,” he says. “It’s sad but I can always do woodwork.”

Tom retired around 2000 and his son and daughter surprised him with a one-day class for learning woodturning from an accomplished turner in Sebastopol. “He no longer turns wood,” Tom says of his teacher, “and retired to get out of woodturning—I retired to get into woodturning.”

His first creation was a madrone bowl that often slipped out of his hands as he was turning it. “That bowl was on the ground more than on the lathe!” Tom admits. “If you don’t hold the tool right, it’ll dig into the wood and pull it off.”

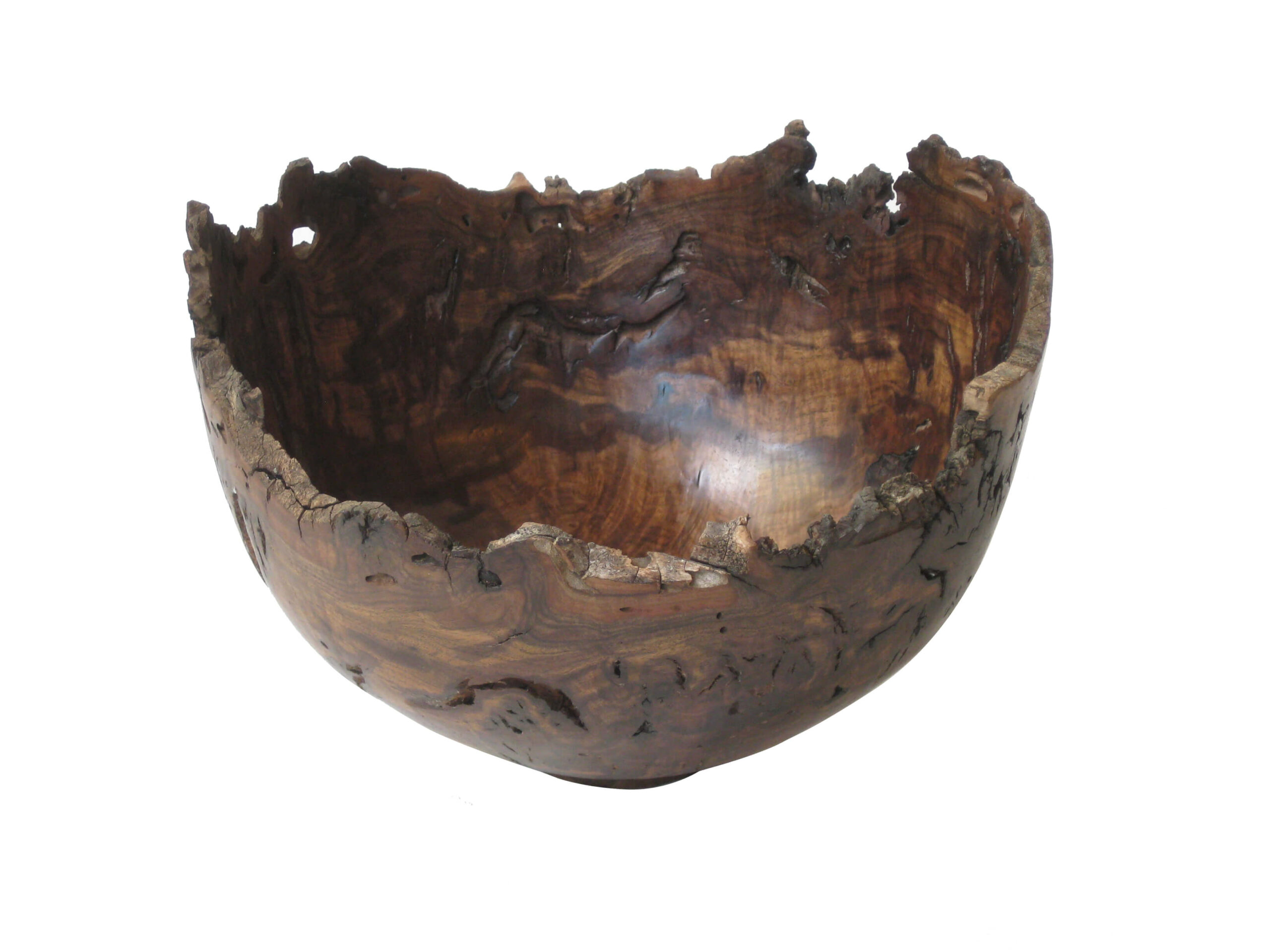

After a couple of decades in turning, Tom recognizes the qualities in a log, branch or stump that make for an alluring piece of wood. He looks for burls, a tree growth in which the grain has grown in a deformed manner. He prefers interesting patterns in the burls, how the curling grain is exposed, and he always keeps his eye on the base of redwood trees where burls are often discovered.

“I also have several boxes of flooring, which is a special hardwood. It’s thin pieces,” he says. “There’s a means of woodturning where you glue the segments together and stack them in rings to make a bowl or vase. That’s my plan for that.”

Tom’s phone is readily available for patrons curious about his turnings (His voicemail message begins with: “Hi, this is Tom. I’m out turning wood and I can’t take your call.”) and his work is exhibited in art studios such as the Main Gallery in Menlo Park and the Gualala Arts Center. He’s also a longtime member of the local West Bay Woodturners and runs the club’s website and newsletter while exchanging ideas with like-minded turners.

There’s an undeniable magic exposed in wood that Tom reveres as he’s turning. Wood doesn’t preserve forever and its ephemeral nature encourages admiration. He relishes in the smell as he cuts in, but once, while slicing into some juniper, the wafting vapors that were released caused him to feel sick. He now uses a face mask—living a full step ahead of society with his stock of N95 masks—to protect from harmful vapor and dust.

In the backyard of his Eichler, as the heat from his fully-functioning furnace keeps him warm, Tom expounds on the joys of woodturning. When he is read back a quote from a biography for one of his art exhibits, Tom smiles. Bashful, he says he couldn’t have described it better:

“Nature is a better engineer than any of us. Those tiny wood fibers are manufactured as if by magic from water, CO2 and sunlight. They are assembled with magic nature glue and presented to us in over 100,000 forms we call trees. I cannot do what nature does, but I can take joy in enjoying the product.”