Any minute now, the phone will ring, bringing news of an award nomination and a new benchmark in his literary career, but during a recent morning, John Billheimer remains untethered to his landline because as any good mystery writer might, he has a keen sense for what’s about to transpire.

He instead breaks open The Wall Street Journal. In between sips of his regular sweet and spicy caffeine-free tea, he contemplates completing the daily crossword puzzle, a 30-minute exercise that he can now afford since retiring as the VP of a small engineering consulting firm that specialized in transportation research.

This relaxed schedule offers further opportunities for John to search for the right words. In 2019, the Portola Valley resident had two books published: Primary Target, his sixth installment in the Owen Allison mystery series, which whisks John back to his Appalachian roots in West Virginia, and the nonfiction Hitchcock and the Censors, a detailed documentation of the painstaking measures the famed director took to create cinema within the antiquated standards of Hollywood code officials.

It’s his treatise on Hitchcock that’s earned John the imminent phone call.

Having served as a judge in previous years for the Edgar Allan Poe Awards (or the Edgars), John is aware that after the nominees are announced online, the feat is personalized by a congratulatory call. The awards are commissioned by the Mystery Writers of America in New York City to honor the year’s best in mystery fiction and nonfiction; John read that morning that Hitchcock and the Censors made the shortlist for best critical/biographical book of 2019.

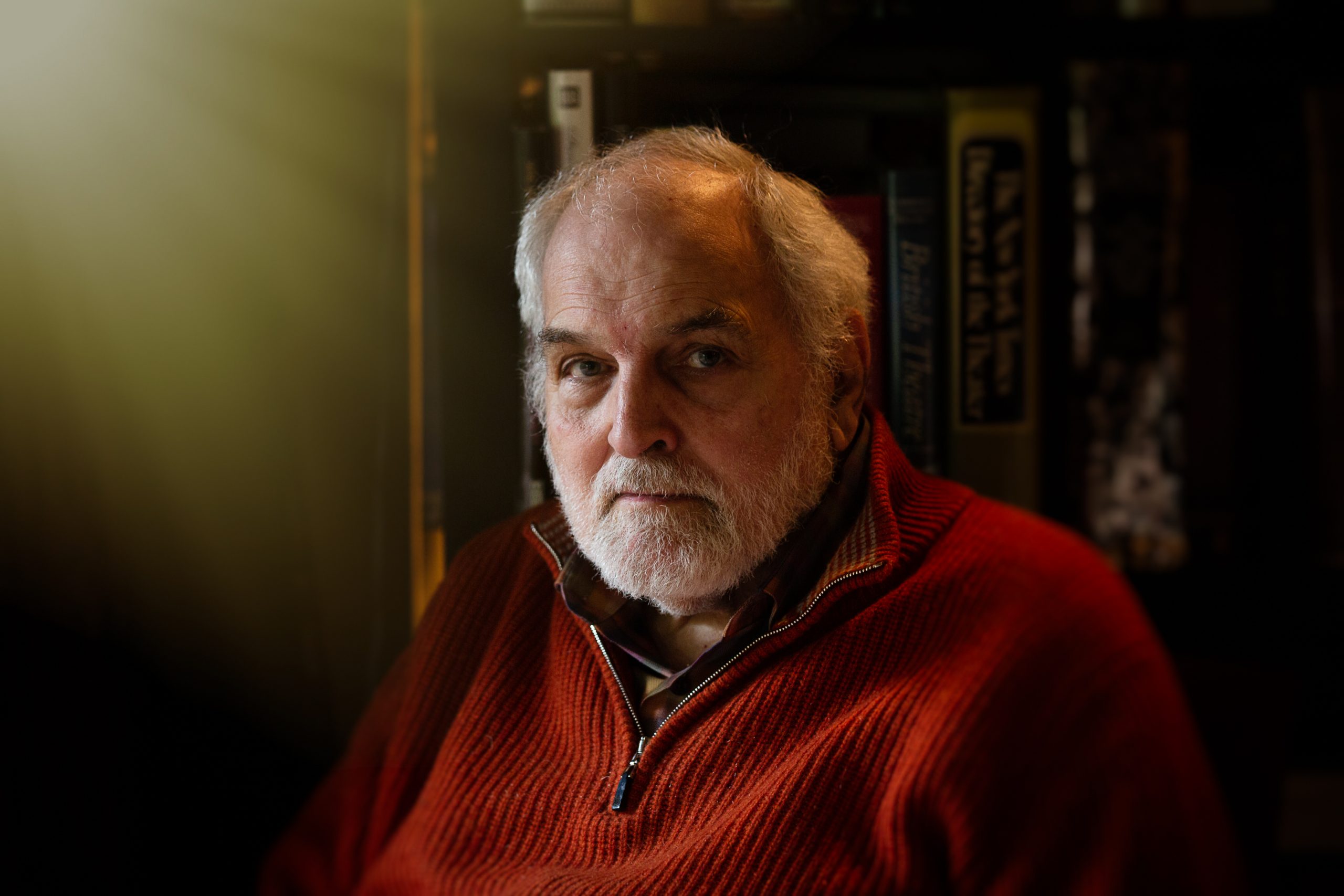

This is his first Edgars nomination and at 81 years old, John embraces the recognition with equal measures of pride and humility. Seated on a couch in the luminous living room of the hillside home he shares with his wife, Carolyn, John clings to his reading glasses as he thinks. His neatly-trimmed beard has more salt than pepper and sometimes, when he looks off to the side, he resembles a distant relative of a grizzled Paul Newman. Perched on a stand on the back patio is a colorful, mobile sculpture of a cowboy and Indian on horseback that swings like a pendulum. It’s by Palo Alto native Fredrick Prescott and the pieces begin to sway slightly in the direction of the wind as John recollects his mysteries.

Carolyn, his wife of 51 years, is on the line in the other room, allowing him to disconnect from thoughts of that impending phone call. He turns to discuss his approach to mystery writing, informed by hardboiled, mid-century greats—Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald—writers who famously diminished attention to plot and mastered the simile.

“Usually, I know the ending, but the path getting there can vary,” John says. “One or two times I’ve changed an ending but most of the times I know who did it. One aspect of my engineer training is that I have to feel that this is plausible and that it can happen. My problem with a lot of mysteries is that the plausibility just isn’t there. Hitchcock hated that in people—he called them the de-plausibles.”

The Master of Suspense captivated John since his first job as a teenage usher at the Keith Albee Theatre in his hometown of Huntington, West Virginia. Years later, John can still hear the audience’s gasps during a murder scene in Dial M for Murder.

His father, Wayne, was a civil engineer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers who would travel up and down the neighboring Ohio River to work on dams while his mother, Mildred, taught at the local Catholic school. Born the oldest of four in November 1938, John was often found in the Huntington library reading World War I dramas or baseball stories.

He’s an avid fan of America’s pastime, rooting for the Cleveland Indians and the Cincinnati Reds alike, and he’s penned two mystery novels centered around a baseball sportswriter named Lloyd Keaton and one nonfiction book exploring some of baseball’s more infamous, egregious misplays. The book, Baseball and the Blame Game, begins with the clever truth: “Baseball is the first thing most men fail at.”

Appalachia colored in the backdrop of his youth. (Which, for semantics’ sake, is pronounced App-a-latcha or, as John divulges, “It sounds like, ‘I threw an apple atcha.’”) The coalfields, integrity of the common blue-collar worker and colorful colloquial phrases seep into John’s novels as easy as sliding off a greasy log backward.

“When I was growing up, each state had its own culture but now the Internet and TV have homogenized everything,” John says. “Steel Magnolias came out when I was writing my first book, The Contrary Blues. I was in the theater watching the movie and Shirley MacLaine says, ‘That woman has a butt like two pigs fighting in a gunny sack.’ The audience broke into laughter but I’ve heard that my whole life. That’s when I became aware that jeez, the world at large might not know these things.”

Leaving West Virginia for his education, John first graduated from the University of Detroit in 1961 before attending MIT for his masters’ degree in electrical engineering. He then earned his PhD in industrial engineering from Stanford in 1971 and afterwards he began working for the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park. His first assignment: Return to West Virginia for a project regarding coal mining. His interactions with the West Virginians would later become fodder for his first novel, which introduces his failure analyst-turned-crime solver hero Owen Allison (whose namesake references childhood friends Robert Owen and Allison Read).

“I thought I was writing a short story but when I got to the end, I thought, these guys are fun—what would happen next?” John says of his debut into fiction, 1998’s The Contrary Blues. “I can think three chapters ahead but when it comes to writing, I outline a chapter in grim detail. But not the book. I need to have enough leeway so I can meander with the plot so that there are surprises for me. And if there are surprises for me, then there will be for the reader.”

The latest installment in the Owen Allison series, Primary Target, has his protagonist reconciling with his collapsed consulting firm that took on transportation projects but fell to cronyism. One dialogue exchange involves characters discussing how the Highway Patrol set policies for when mobile phones hit the market. His prose is full of action, not just due to the bombs exploding in garages or shootouts at the airport, but when his characters talk, they also tend to walk, creating a forward momentum that pummels his stories onward.

Prior to solving his own mysteries, John worked as a specialist in modeling, analyzing and evaluating transportation systems for SYSTAN, Inc. in Los Altos from 1972 to 2005. He helped establish the California Motorcyclist Safety Program, a statewide program of mandatory training that saw motorcycle fatalities drop over 70% during its first 15 years. And if you’ve ever been caught driving solo in 101’s carpool lane, John’s research helped the CHP to establish HOV lane enforcement policies. His engineering career was fruitful, but looking back, he recognizes a resemblance between his life and his fiction.

“I had been almost too laid-back. I didn’t go out beating the bushes to develop things and we probably would have been better off with more salesmen,” he says now. “We eventually fell prey to the same thing in Primary Target: A big job we won was taken away from us. We had a small business for 33 years that eventually fell fallow to bureaucracy.”

Acknowledged in the front of Primary Target is the Wednesday Night Wine Tasting and Literary Advancement Society, a writing group John has been a member of since the mid-1980s. The group keeps him humble, telling him what works and what needs editing, but he says their most important function is to crack the whip on deadlines to ensure he produces at least a chapter a month.

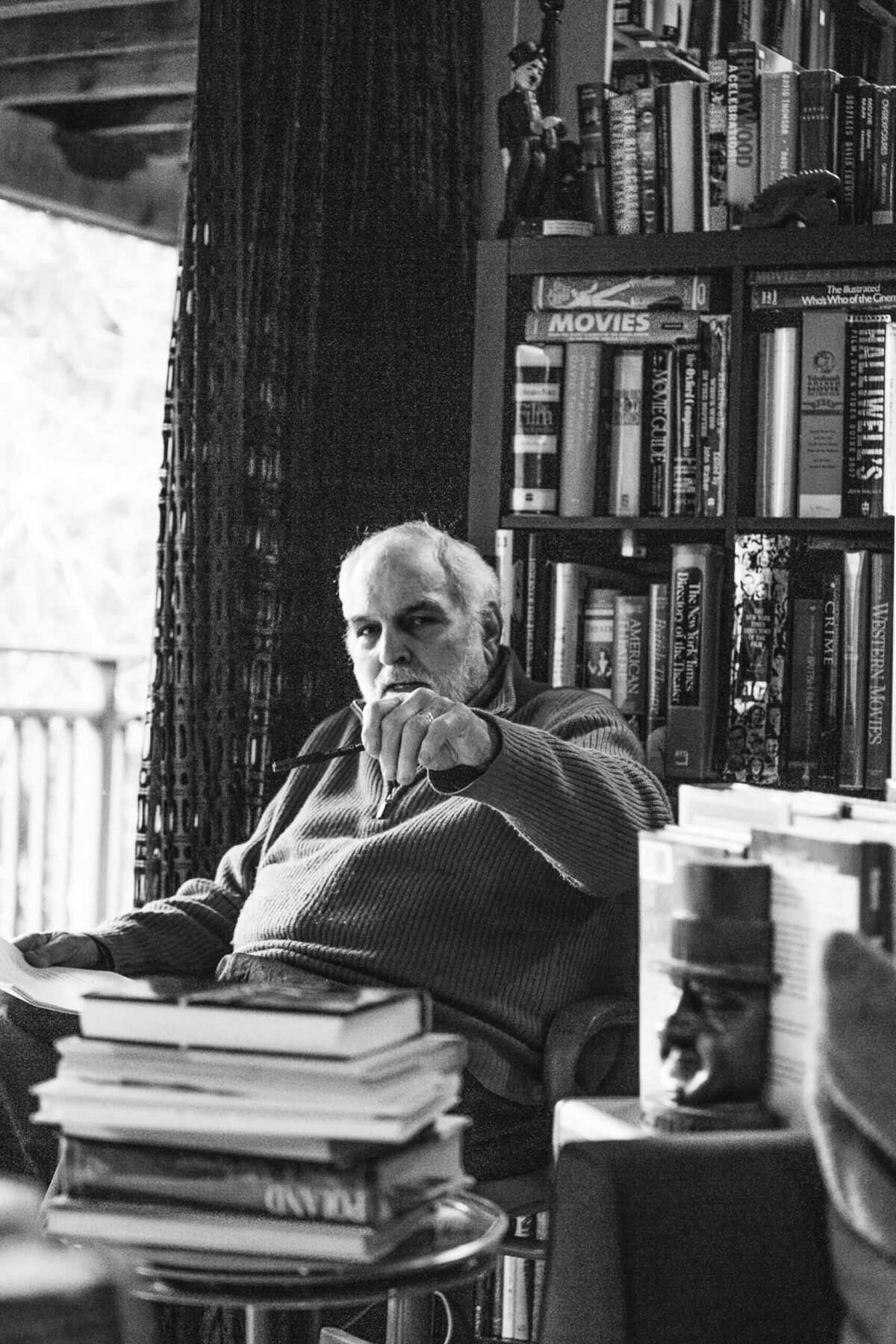

When he’s writing, John prefers to use a pen and paper, lounging on the couch in his downstairs office and since he’s a lefty, his hand sometimes smears the story as it inks out, leaving him unsure of what he just wrote—furthering the layers of mystery. He’s casting around for ideas for his next book idea and perks up at the suggestion of somehow introducing the protagonists from his dual mystery series, Lloyd Keaton and Owen Allison, in one story.

But that’s a mystery he’ll solve some other day. Carolyn is off the phone now, the line is free and John returns to reading. The Prescott sculpture still gently sways on the patio like the eyes of a Kit-Cat Klock while from a distance, across the country in New York, someone begins to dial 6… 5… 0… on the telephone keypad.