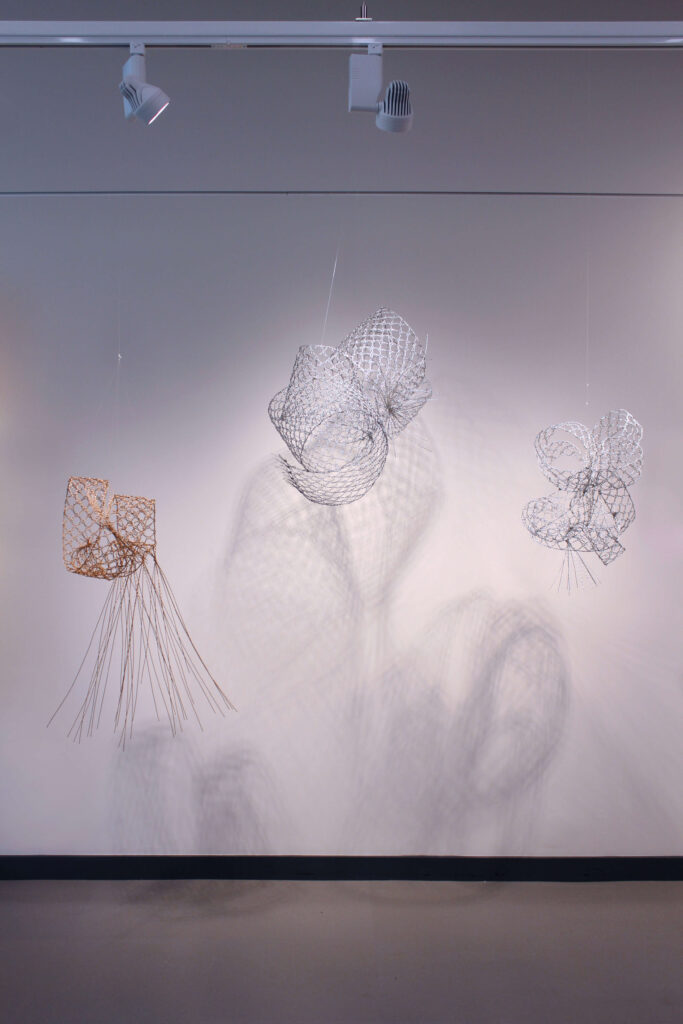

Light reflects off twisted bronze and stainless steel, while shadows cast by the airy forms dance on the wall. Elegantly fluid wire sculptures, whether ceiling-suspended, wall-mounted or free-standing, command attention and instill wonder. Lace Four: No Loose Ends floats overhead, slowly turning with the room’s air currents. Curving ribbons connect in a voluminous spray of wire ends glittering under a spotlight while projecting an outsized shadow on the wall.

This is just one imagining of Peninsula sculptor Barbara M. Berk, who is currently in the final stages of executing a project for the Burlingame Public Main Library—her largest installation to date. Invited to create a sculpture to suspend from the atrium’s chandelier, high above the library’s central staircase, Barbara crafted a series of open spiral elements in three sizes.

“Initially, it was quite daunting,” she shares. “The space is huge, the chandelier is only 55 inches in diameter and the total weight of the elements cannot exceed 15 pounds.” Given the project’s physical parameters, Barbara realized a single piece would either be too heavy or dwarfed in the setting. “Ultimately, I came up with the solution of suspending multiple elements at different heights, visually filling the space,” she says.

Looking back, Barbara originally ventured down a very different path. After earning her graduate degree in Russian history, she spent her early career working in advertising space sales for magazines in New York. “Then I discovered antique jewelry,” she recalls, “and while I didn’t know what I was looking at, the pieces spoke to me.” She learned more about antique jewelry and how to evaluate it, thinking she could become an appraiser, and enrolled in jewelry making classes to better understand how pieces are made.

Relocating to San Diego for her husband’s biotech career in 1991 changed everything. A chance encounter with professor Arline Fisch, founder of the metalsmithing program at San Diego State University, prompted an invitation to attend Fisch’s graduate-level “Textile Techniques in Metal” class. “And that’s where the magic happened,” recounts Barbara. “I had been sewing since I was a young girl, making stuffed animals and my own clothes. But with Arline, I learned how to weave, knit, crochet, braid, twine and make lace with silver, copper, brass and titanium. And I learned that I loved working directly with metal—my fingers particularly liked weaving and lace-making.”

As she explored the possibilities of this new artform, Barbara wore her attention-grabbing silver and copper brooches at trade shows. “They really popped against my navy blue blazer,” she says. “I walked up and down the aisles, marveling at incredible gems, and the dealers only wanted to talk about my brooches.” Even facing sparkly competition, Barbara could see her creations were showstoppers—and she began to envision a future in metal.

Barbara founded Barbara Berk Designs in 1992 to create small, wearable sculpture in precious metals. A few years after starting her business, she moved with her husband to Foster City where they settled into a waterfront home. By 2013, in search of new challenges, she toyed with the idea of working in a larger scale, off the body. Needing more space, she rented a studio at the Peninsula Museum of Art in Burlingame.

“I spent the first 18 months or so figuring out what direction I wanted to take,” says Barbara. “Since the metals I was most familiar with were too soft to sustain large work, I experimented with a variety of industrial metals, looking for the right combination of physical properties and working characteristics that would balance and reinforce the integrity of the textile structures.” She discovered that stainless steel and phosphor bronze were best for weaving and for implementing the 16th-century lace techniques she had explored 20 years before.

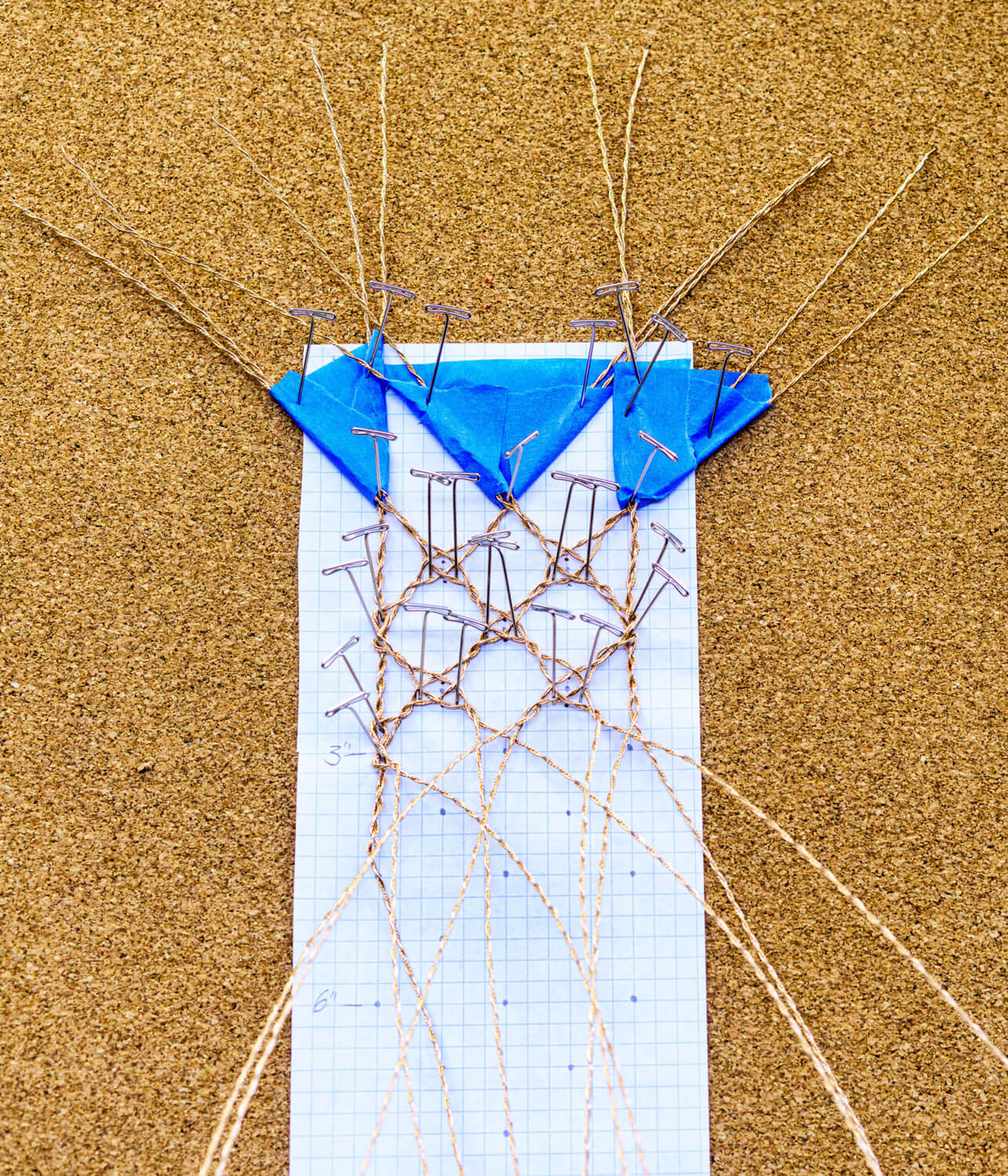

Barbara’s process entails creating a lace pattern on graph paper and securing it to a cork board resting on an easel. She then twists wires to the specific length she needs for the individual piece, attaches them with T-pins through the paper pattern into the cork and begins making stitches, one at a time, proceeding in diagonal lines to the bottom of the pattern. Barbara then curves, loops, twists, interweaves, sews and embroiders the flat lace “fabric” into a three-dimensional form.

“I love working larger-scale,” she confides. “I’m no longer constrained by requirements of fit and comfort. I’m free to experiment, free to follow where my fingers and the metal want to go.” Other advantages: mistakes are no longer costly and she doesn’t have to map everything out in advance. “I don’t have to know precisely where I’m going before I start,” she says with relish. “The work is still meditative but it’s also liberating and fun.”

Barbara’s sculpture is included in the permanent collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and has been exhibited in museums and galleries both locally and across the country. Most recently, her stainless steel pedestal-piece Lace Twelve: Oskar Schlemmer’s Dancer was selected for On the Edge: The de Young Open, a juried exhibition of Bay Area artists celebrating the 125th anniversary of the de Young Museum. “It was a phenomenal boost at a time when I didn’t realize just how much I needed one,” reflects Barbara. “It was recognition, reinforcement, validation—something wonderfully positive during the depths of the pandemic last year.”

Barbara has since moved into a private studio complete with gallery space in an industrial section of San Carlos. Scheduling viewings by appointment, she is enjoying the additional square footage, the natural light, the high ceilings and the ability to fully display her work. That includes setting up a framework that mimics the outside rim of the Burlingame library’s chandelier, from which she suspends the lace elements.

“It’s a very exciting time,” shares Barbara. “One-third of the open spirals are complete and hanging in the studio, and I can see the piece coming together; the spirals interact with each other—they shine and cast these mesmerizing shadows on the studio walls.”