Words by Jordan Greene and Sheri Baer

On the morning of November 8, 1957, 36 passengers and 8 crew members boarded a long-range Boeing 377 Stratocruiser aircraft at San Francisco International Airport. With bags and suitcases packed for the journey, they hugged their loved ones goodbye and took off for Hawaii in what was supposed to be the first leg of a round-the-world flight.

But the plane never arrived.

To this day, Pan American Flight 7—called Clipper

Romance of the Skies—remains one of aviation’s greatest mysteries, and it originated right here on the Peninsula.

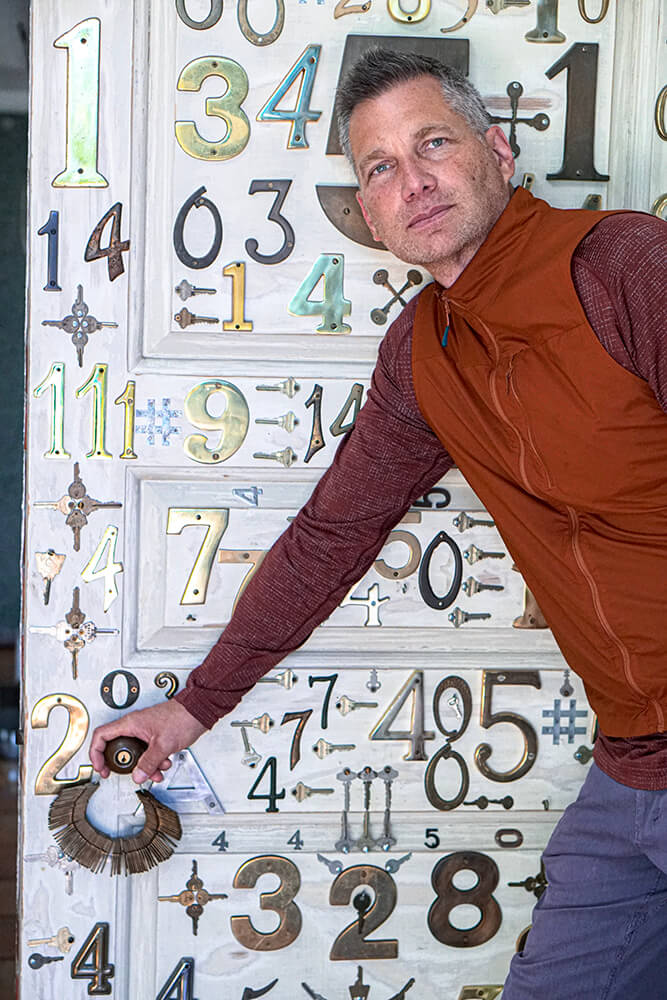

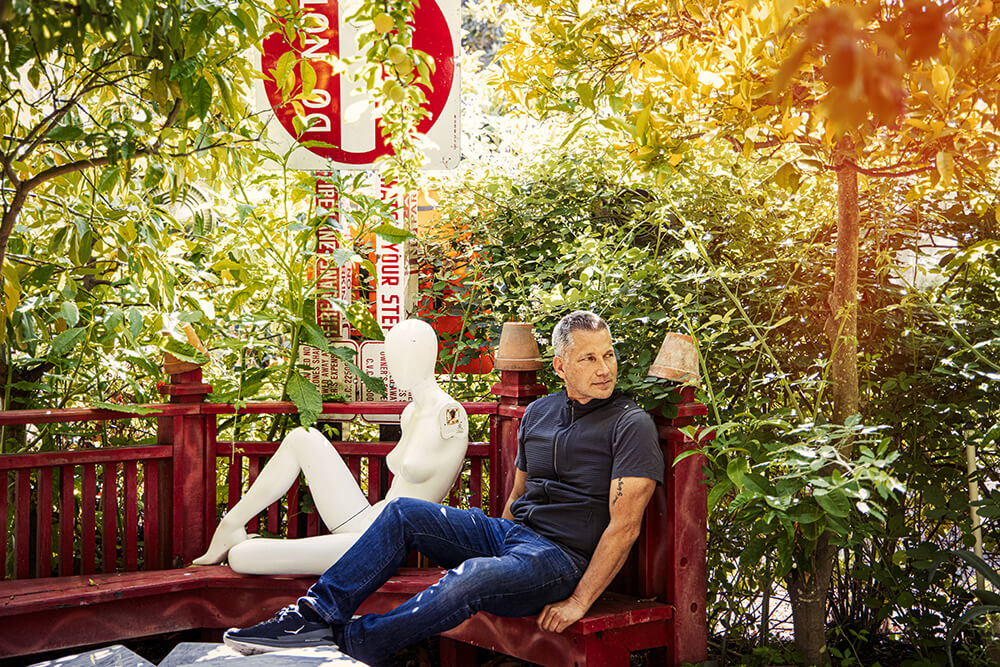

Not many personally remember the details of the crash, but there are a few who remain determined to find answers. Ken Fortenberry and Gregg Herken—two men motivated by personal connections to the plane’s disappearance—crossed paths online via a messenger board about 20 years ago. After independently researching the tragedy for decades, they’ve worked together for years since, chasing down potential leads and exhausting every possible library resource and archive.

Was it a mechanical failure? Sabotage? An explosion? Or an act of intentional mass murder-suicide that killed the 44 people on the plane, including 12 from the Bay Area? Having drawn their own conclusions, Ken and Gregg now share a resolve to create a memorial to honor the lives lost.

“To me, for these people, their last good day on Earth was in the San Francisco Bay Area and many of them lived here—this was their home,” explains Ken. “They got on a flight on vacation or business and halfway through the flight, they’re gone. I think that people’s lives are worth more than just a headline in passing.”

At 11:51AM, Pan Am Flight 7 lifted off from SFO. The weather was perfect—clear skies and calm seas. As the 36 passengers settled into their seats, the pilots announced a smooth and easy 10-hour flight to Honolulu. Flight attendants started roaming the cabin to serve champagne, caviar and a seven-course dinner. With tickets for the flight running around $300 at the time, the trip was costly, but a luxurious experience.

At 5:04PM, the pilots radioed to ground control with a routine position report, which they did every hour. But at 6:04PM, there was silence. No check-in. But also no distress call. More time passed, and still not a word. At 6:35PM, Air Traffic Control issued an urgent alert: Pan Am Flight 7 had vanished.

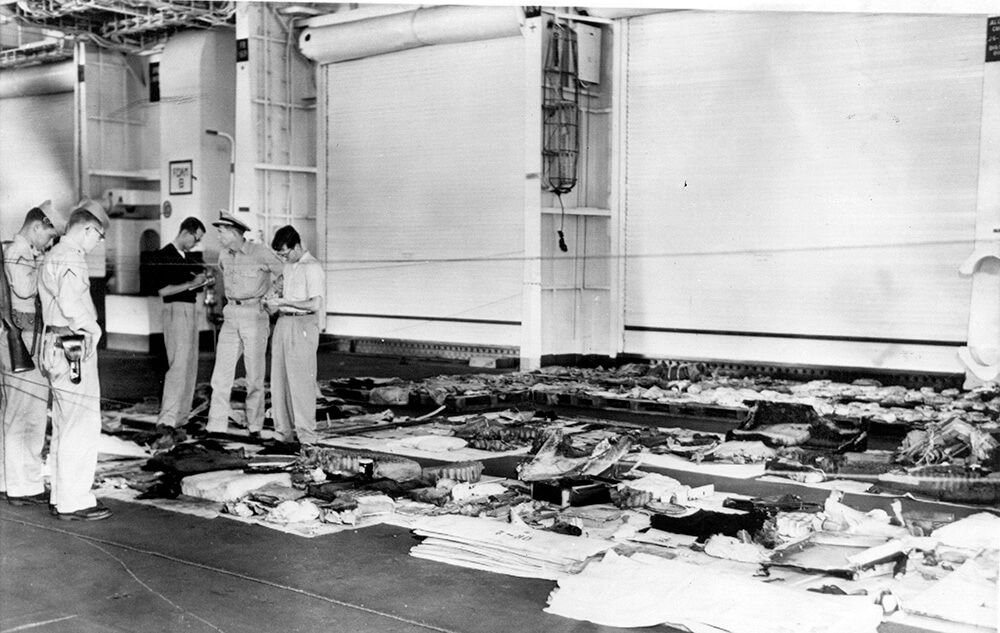

The next day, an intensive air-sea search began. Submarines, aircrafts and all ships near the last reported position of the plane scoured the area. It wasn’t until November 14 that a search plane spotted probable wreckage on radar, which led to the discovery of 19 bodies and debris floating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, 955 miles northeast of Honolulu. Wristwatches that broke on impact helped pinpoint the moment the plane plummeted into the water, 5:25PM, 21 minutes after the plane’s last routine position report and about 90 miles off course.

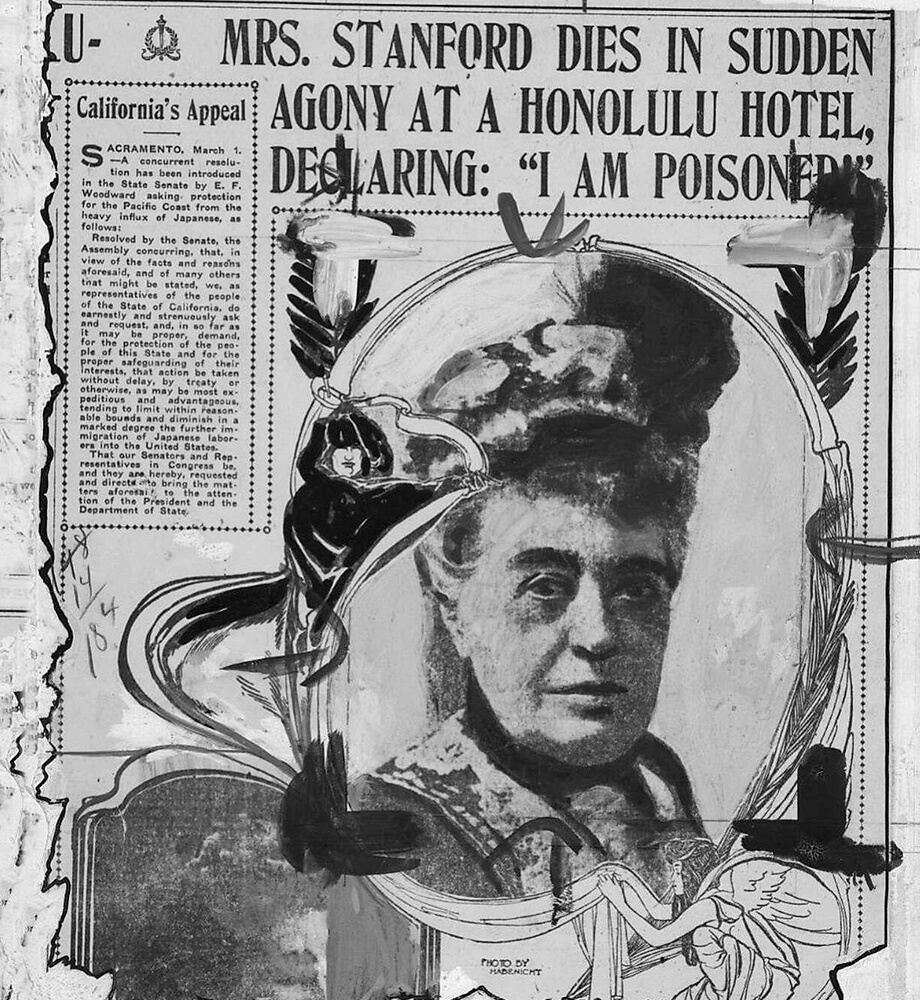

Pan Am stewardresses Marie McGrath and Yvonne Alexander

As grieving families waited for answers, the Civil Aeronautics Board launched its investigation into what had happened to Pan Am Flight 7. It took until January 1959 to deliver a disappointing, inconclusive report: It could establish “no probable cause” for the crash.

Ken Fortenberry was living in a brand-new house next to plum orchards and a dairy farm in Santa Clara when he learned that his father, Pan Am 7’s second officer, was missing. Before relocating to Santa Clara, Ken’s family had moved from New York to San Mateo, where William (Bill) Fortenberry played an instrumental role in establishing Shoreview Methodist Church. “My dad loved California, absolutely loved it,” recalls Ken. “It was just a real special place to him.”

Six years old at the time, Ken woke up on a Saturday morning to find his house full of strangers. “I don’t recall specifically the moment my mother told us the plane was missing, but I do recall just being a kid and crying my eyes out,” he says. Ken remembers his mother saying, “Your dad’s a great swimmer, Son. They’re gonna find them somewhere.” His father’s body was never recovered.

Although 65 years have passed, Ken remains grateful that happy recollections also linger, including camping trips with his father to Yosemite and Clear Lake. ”He’d always talk about how proud he was of us three boys,” Ken says. “My dad was gone for lengthy periods of time flying, but when he was home, he was also home for weeks at a time. And those weeks were memory-makers for us.” After the crash, Ken’s family moved back to South Carolina to be closer to his mother’s family. As he grew up, he turned to old letters his dad had written from overseas. “He was a prodigious writer,” Ken notes. “And those letters became my dad talking to me.”

In 1957, Gregg Herken had recently moved to San Mateo from Denver and was having a hard time fitting in at his new school. “I had a buckskin coat and I thought it was the coolest thing, but it made me stand out,” he recounts. Marie McGrath, Gregg’s substitute teacher at Sunnybrae Elementary, quietly suggested to his parents that he “ditch the coat.” Not much later, Gregg showed up to school in a new San Francisco Giants jacket. “I wore that to school and suddenly, I was popular,” he reminisces. “I owe Marie McGrath for that.”

A Pan Am stewardess, Marie doubled as a substitute teacher, a common second career during aviation downtime. Gregg, who graduated from Aragon High School in 1965, recalls Marie sharing stories of her adventures and bringing food from the Clipper for a class luau. “She told us about Hawaii,” he recollects, “and for a fourth-grader who had just moved from Denver, this was very exotic stuff.” Marie also substituted at Abbott Middle School, where Gregg’s mom worked as a secretary.

Gregg was sitting in class when the principal announced over the PA system that Miss McGrath’s plane was missing. “At the time, I just imagined it flying into a cloud and not coming out again,” he remembers. “I’ve always felt grateful to Marie for what she did, for helping me adjust to my new life as a kid in California.”

In addition to William Fortenberry and Marie McGrath, who lived in Burlingame, the majority of Pan Am 7’s crew was based in the San Francisco Bay Area. “Pan American had a huge presence in San Francisco with thousands of employees,” notes Ken.

Through his research, Ken also came to know the backstories of Bay Area passengers. “They were all fascinating people,” he relays, as he summarizes some of the anecdotal details. Ruby Quong of San Francisco resigned her position as a registered nurse two days before the flight to travel to Hong Kong to care for her ailing mother. Edward Ellis, an executive with McCormick spices who lived in Hillsborough, was traveling to Honolulu to address a U.S. Chamber of Commerce convention. San Mateo machinery repairman Fred Choy planned to visit his seriously ill father in Hawaii. Louis Rodriguez, a San Francisco surgical orderly and father of three, was en route to his mother’s funeral. Pan Am pilot Robert Alexander and his wife and three children, who lived in Los Altos, heard Honolulu’s palm trees and lapping waves beckoning. “He was just a pilot on vacation,” Ken grimaces, “but they died. They all lost their lives.”

Extending beyond the Bay Area, Ken connected with a Michigan woman named Norma Clack, whose uncle was traveling with his wife and four children. “They were going back to Tokyo where he was an executive with Dow Chemical Company. They were all lost.” For years, Ken kept a picture of the Clack family on his desk: “Just to remind me, ‘You’re not doing this just for you, Ken, you’re doing this for these other families that have no closure.’”

Ken Fortenberry recalls the exact moment that triggered his maniacal campaign to find answers. When he was 13, he wrote a letter to the Civil Aeronautics Board, asking for updates on the crash investigation. “I got a bureaucratic BS response just kissing me off,” he recounts—essentially nothing had been done on the case in seven years. “I remember walking back to my house from the mailbox, just mad as hell. And at that point, I vowed as a kid that I’m gonna find out what happened to that plane if it takes me the rest of my life.”

Committed to a formidable goal, Ken faced a tough slog in the decades immediately following the crash. “You gotta remember that we didn’t have the Internet back in those days,” he says. Even tracking down an address was challenging, but Ken wrote every letter he could. “And long-distance telephone calls cost a fortune,” he points out. “I’ve been to every library you can imagine; I’ve been to archives everywhere and I kept every note I ever made on this thing from the time I was a kid.” Admittedly influenced by his childhood trauma, Ken ultimately became an editor and award-winning investigative journalist—with one constant thread: “Every spare moment I had growing up and even as an adult, I always researched this plane crash.”

Meanwhile, Gregg Herken launched his own obsessive investigation after starting work as a curator at the National Air and Space Museum in 1988. With the National Transportation Safety Board located across the street, he recognized an opportunity to discover what had happened to Marie’s plane. “I found that it was actually one of the outstanding aviation mysteries,” he says, before explaining that there were three prime suspects in the case: “One was the purser who was suicidal and who had left a copy of his changed will in the glove box of the car that he parked at the airport. The other was a passenger who bought a one-way ticket to Hawaii and three insurance policies on himself and was deeply in debt. The third was a problem with the propellers, which were prone to overspeed and had caused problems before.”

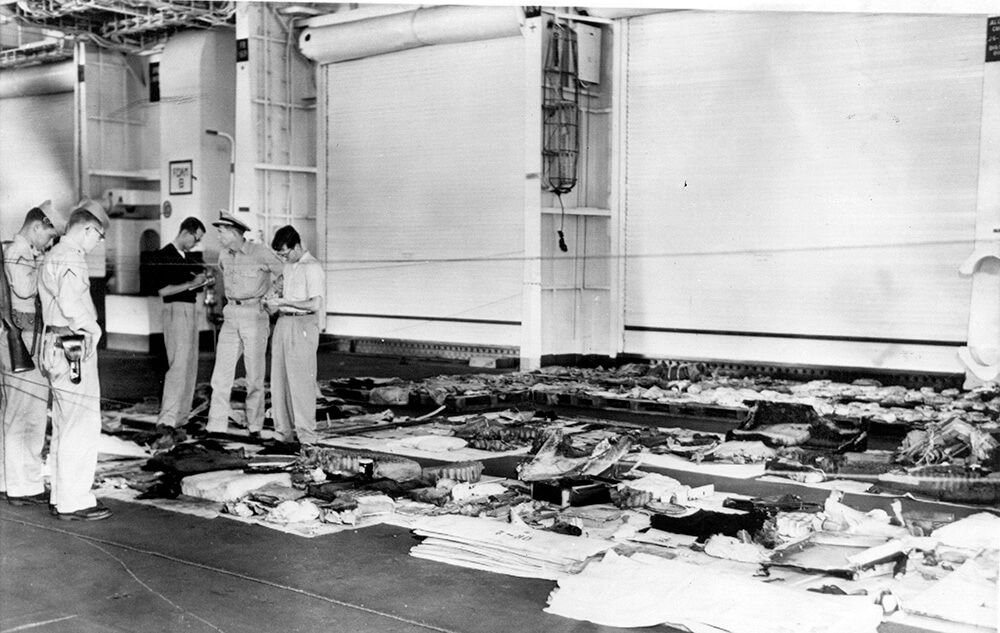

Reporters and Navy officers inspect debris recovered from the crash site

As their individual investigations progressed, thankfully so did technology. “Really, the advent of the Internet brought the story alive and made it much more possible to chase down leads,” underscores Ken. It also made it possible for the two Pan Am 7 sleuths to find each other. About 20 years ago, Ken posted a request for information on a messenger board. “And Gregg responded, ‘Hey, I’m interested in this case too!’” Gregg flew down to North Carolina to meet Ken, and “we struck it off from the very beginning and have been research colleagues ever since.”

Even as a 13-year-old, Ken thinks writing a book was always in the back of his mind. In 2020, he published the culmination of his life’s work: Flight 7 is Missing: The Search for My Father’s Killer. Over the years, he had waffled back and forth on the mystery, often for decades at a time. Initially focused on mechanical issues, he uncovered the story of William Payne, a former Navy frogman who had bought a one-way ticket and an excessive amount of life insurance before the crash. He also dug into the background of another potential suspect, Eugene Crosthwaite, a disgruntled Pan Am purser from Felton. With each new clue, Ken would find his perspective shifting. “One minute, I’d think it was an accident,” he acknowledges. “Next thing, I’d think Payne blew it up and then next thing, Crosthwaite blew it up.” In his quest for answers, Ken futilely reached out to Crosthwaite’s stepdaughter, Tania, who he says, “stiffed me for decades.”

And then he got a Facebook message out of the blue: “I think it’s about time we talk.” Ken flew to Houston to meet Tania the next day. “She pretty much laid it out that her stepdad was suicidal and out of his mind,” recounts Ken, who now blames Eugene Crosthwaite for his father’s death. “The information she gave me helped me paint more of a picture and I had a forensic psychologist weigh in on it. And he pretty much concluded what I did as well.”

However, Gregg, now a retired history professor living in Santa Cruz, reached a different conclusion. “I think it was a catastrophic mechanical failure,” he conjectures. “There was a similar incident a few years before with the same type of plane where the propeller spun out. They almost lost control of the plane but were able to make an emergency landing on an island. I think that something very similar could have happened in this case.”

Image: Courtesy of Ken Fortenberry

Having exhausted every resource available, the two are comfortably reconciled with the “agree to disagree” investigative outcome. “We have our opinions,” observes Ken, noting that no one will know for certain until they get to the bottom of the ocean and find the plane. “Gregg’s just a great friend and for him to be by my side all these years has been very special.”

As the wreckage of Clipper Romance of the Skies degrades on the seafloor, memories of the ill-fated plane also fade over time. With no burial site to visit, Ken and Gregg believe it’s imperative that the precious lives lost aren’t forgotten. “This crash did a lot to change safety regulations and expectations for aviation,” states Ken. “This was home to so many of them, and I just think their lives need to be remembered in some way.”

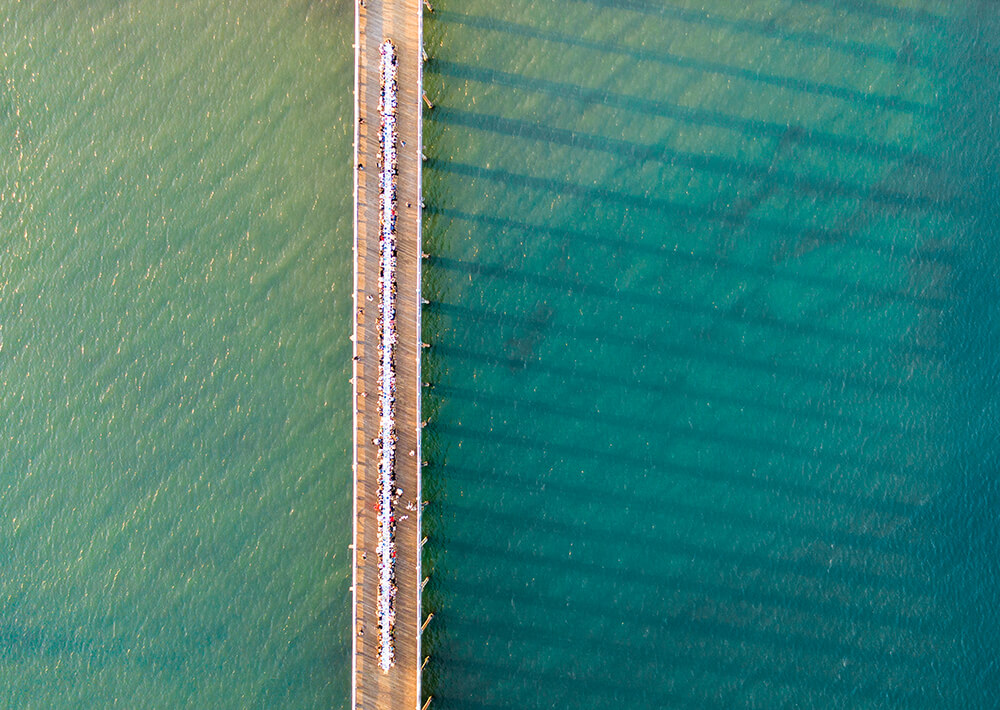

Ken created the Pan Am Flight 7 Memorial Committee with the goal of establishing a permanent tribute to the 44 victims. With GoFundMe and Facebook pages set up to educate and raise money, all that remained was finding an appropriate setting for the plaque. After tireless and often frustrating outreach efforts, the Memorial Committee finally found a warm reception in Millbrae. In late July, the City Council agreed to the placement of a memorial within the city, likely in Marina Vista Park, just across 101 from SFO. With the 65th anniversary of the crash being commemorated this year, Ken and Gregg eagerly anticipate the unveiling of a formal memorial, which will permanently cement the flight’s Bay Area ties. “I just feel so close to San Francisco, even today,” reflects Ken. “That’s where I left my heart. That’s where I left my dad.”

Photo: Courtesy of Marietta Asemwota

Photo: Courtesy of Marietta Asemwota

Photo by Annie Barnett

Photo by Annie Barnett Photo by Annie Barnett

Photo by Annie Barnett

Image courtesy of Audrey Luke and SMCHA

Image courtesy of Audrey Luke and SMCHA