words by Silas Valentino

On the wall of the woodshop in the back of Michael Osborne’s house in Menlo Park is a neatly-nailed notecard detailing the antiquated word lagniappe.

Quoting Mark Twain’s memoir Life on the Mississippi, this ornamental placard describes the noun—which is Louisiana French by way of Spanish—as “the equivalent of the thirteenth roll in a ‘baker’s dozen’” or something thrown in for free—for good measure.

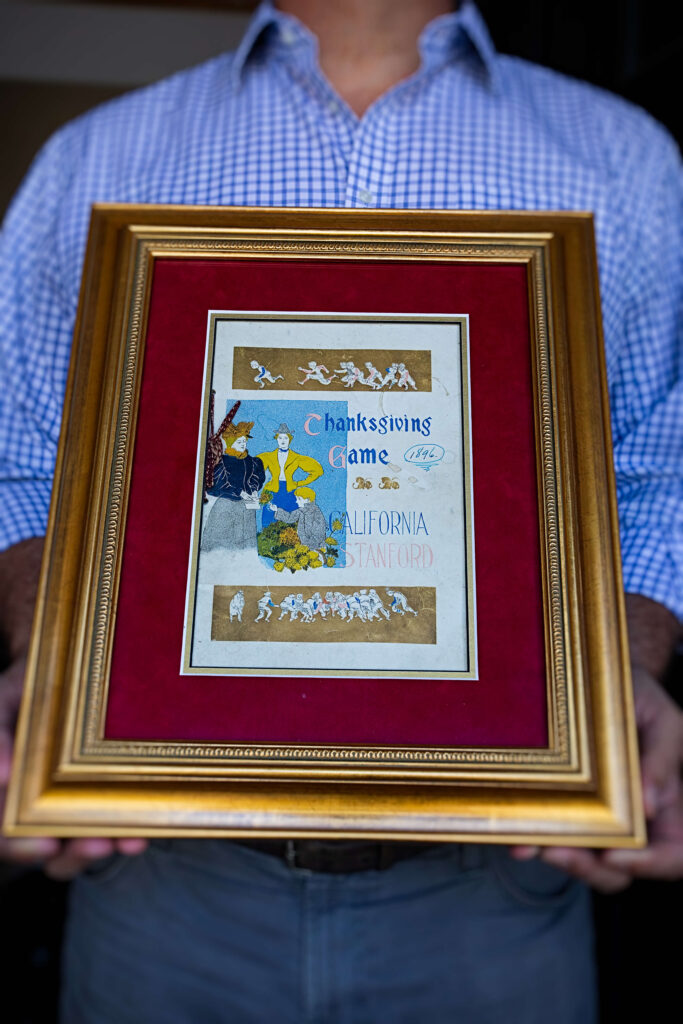

Michael received the word following a routine exchange for this backyard artisan. An architect friend sent him 13 cut-off pieces of upcycled blackbutt wood from a late 19th-century tennis club in Australia. The deal was that Michael would make him a knife out of the free timber. Following their transaction, tucked in a greeting card, was the definition.

Now the unexpected virtue of lagniappe flows through Michael as he works in his shop every day, hand-carving gorgeous variations of woodcraft.

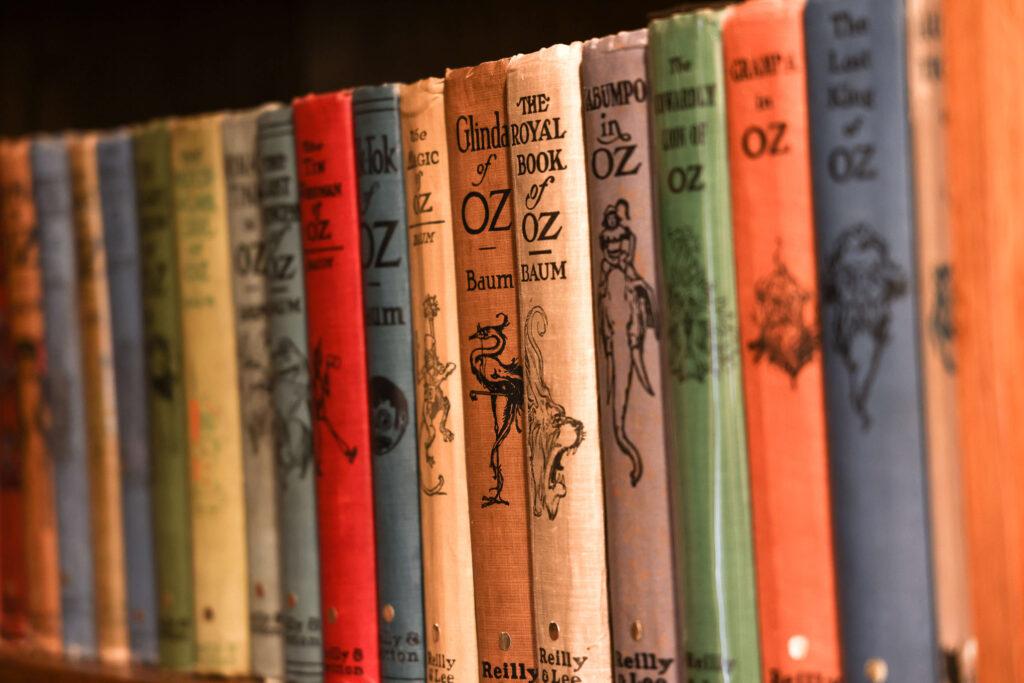

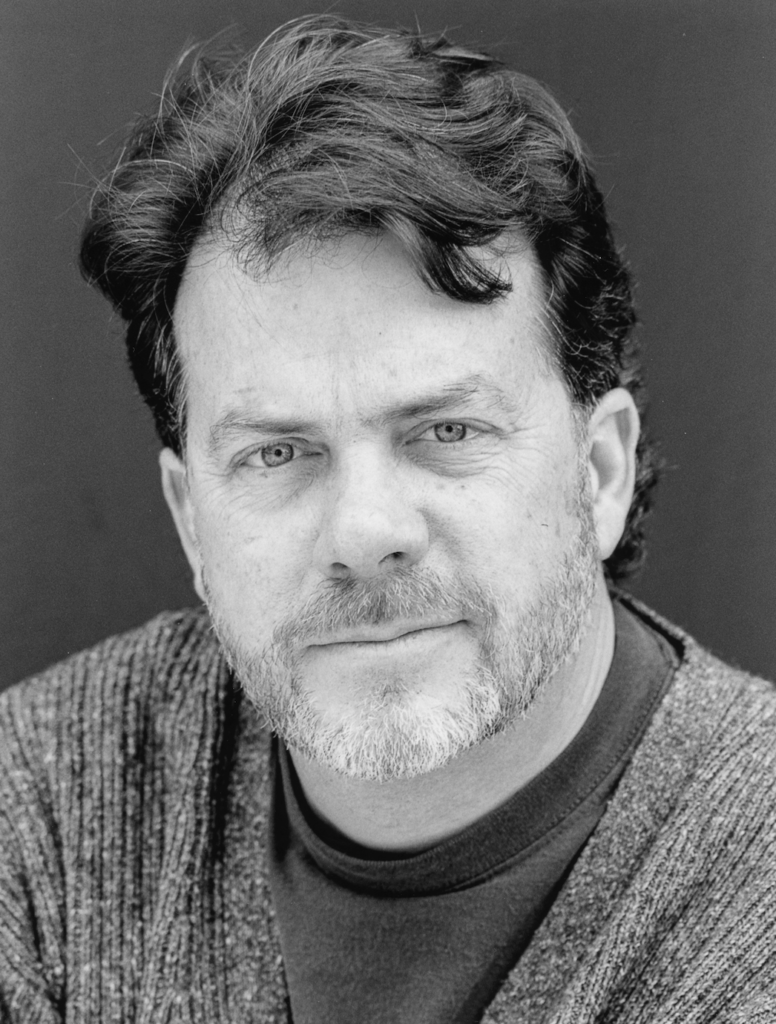

The retired graphic designer started working with wood a few years ago after a neighbor tipped him off to night classes held at the Palo Alto Adult School. He’s since become self-taught (sometimes finding ideas in the winsome Mortise & Tenon Magazine) and his output is active, producing several styles of chairs, a ukulele, spoons, knives, cutting boards, jewelry drawers, an array of hardwood boxes and even an urn for a deceased friend.

He treats the passion with the same diligence previously deployed during a career developing recognizable designs for household brands. Among his successes, his firm Michael Osborne Design is the reason a bag of sea salt and vinegar-flavored Kettle potato chips is the color of ocean blue and it was the brains behind Beverages and More adapting to the BevMo! rebrand. There’s also a good chance you’ve mailed a letter using one of the stamps he designed for the USPS.

Michael is guided by the philosophy that a well-defined problem is half-solved, so as a recent retiree, he made sure his idle hands would not end up at the wrong workshop.

He chisels and cuts slabs of wood purely for the pleasure of creation, neither motivated by financial gain or fame. In the end, he revels in the joy of giving or trading with fellow craftspeople. He’s swapped for an oil painting, a hand-knit beanie, a couple of pounds of dried salmon and from a non-creative, a bottle of whiskey not found on the West Coast.

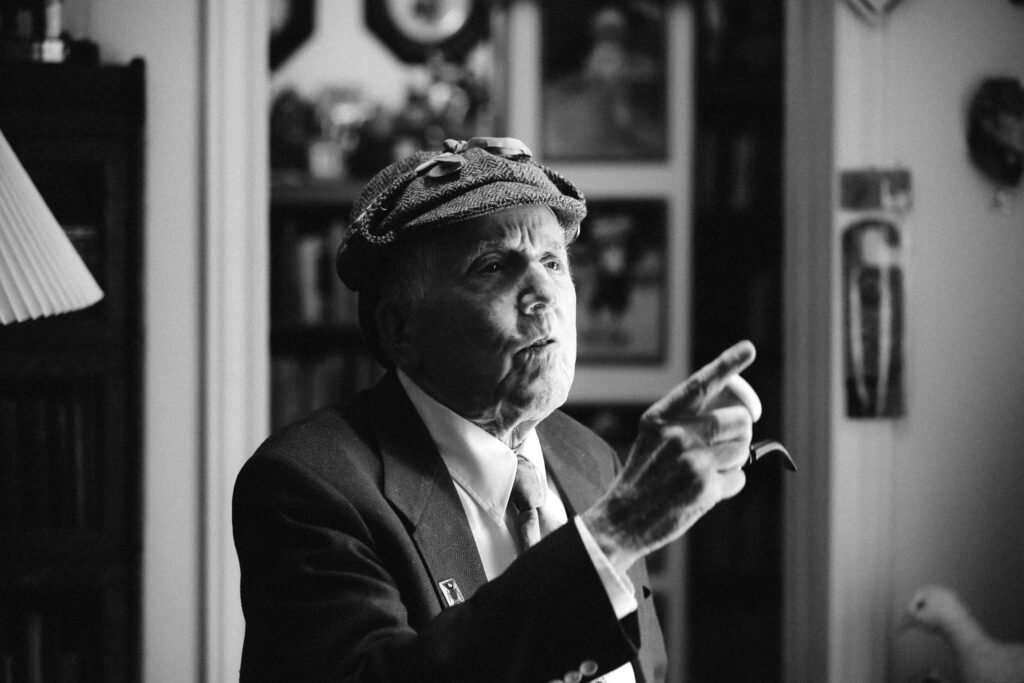

“There’s no client, no pressure and no deadline,” Michael says, seated outside his woodshop on a recent afternoon. “I get up and come out here like it’s my office. I’m the happiest when I’m making something. It gives me great pleasure. Every day, I come back to my wife Jane with a finished thing. I take reused wood or wood scraps that would have otherwise been thrown away and make something that somebody could love. I can do that; it’s nice to be able to do that. And it happens right here in my church.”

He motions to his backyard where an oak tree provides cool shade and a few boxes of buzzing bees in the distance produce honey. (He’s also known for handing out jars of honey as a lagniappe.) He keeps a BB gun nearby to wallop on some aluminum cans perched up on a post while musing between projects. In lieu of gospel, the music heard at Michael’s church is likely The Beatles or solo Paul McCartney.

In the foreground is an art installation shaped as an abstract heart, just one of seven of his contributions to the Hearts in San Francisco series that celebrates public art. Michael has amassed a healthy accumulation of art spanning paintings, statuettes and photography, and he admits that they’ve run out of wall space, which spawns creativity for their placements.

Jane Anderson, his wife for the last decade and a fellow accomplished designer with a talent for gardening, teases Michael for his decision to keep his cardiac sculpture and another hefty installation piece in their backyard exposed to the elements.

But the casualness fits Michael’s straightforward demeanor. He’s frank, but not careless. And for someone who has a keen eye for designs that lure, Michael does not appear burdened by conveying some flashy perception of himself. He opts instead to remain grounded and open to sharing—like how he earned the bandage that’s presently wrapped around his hand.

“I accidentally rasped my thumb,” he says, referring to a filing tool used for abrading a recent project. “But I have all my digits! That’s the thing with knives and something as seemingly innocuous as a rasp, you can easily take your finger off. But I still go into the house bleeding. Ask Jane if Michael ever comes in bleeding… half the time I don’t even realize it.”

Michael’s hands have endured their share of wear. He’s had surgery on both hands for Dupuytren’s contracture, a condition where knots of tissue form under the skin, but he maintains a positive outlook. “I figure that I’m 70 years old and am in pretty good shape,” he says, “so if that’s the worst thing about me, I’ll take it.”

Michael has been active with his hands and toying with design ever since his parents brought home an original set of Colorforms, the creative toy with geometric shapes that cling to a black vinyl backdrop. He was in heaven creating his own patterns. Growing up in Cincinnati, he was socially malleable, weaving between painting the sets for the school play and practice for the baseball and football teams.

Following a friend’s advice, he found himself on the Peninsula in the early 1970s, where he soon enrolled in graphic design classes at Foothill College. When Michael entered the industry, graphic design was a fledgling profession, then referred to as “commercial art.” He rose with the field, earning his degree from the esteemed Art Center College of Design and learning the trade by hand and not a computer.

“I taught design at the Academy of Arts for 25 years and my biggest frustration was that young designers do not use their hands,” he bemoans. “They don’t have the hand-eye coordination to draw a line and then correct the part that is not perfect. Only your eye tells you that.”

At another school much closer to home where he’s the student, Michael has carved out a crafty reputation amongst his peers and fellow woodworkers.

“They know me at the Palo Alto Adult School for digging into the dumpster,” he says with a grin. “It’s not garbage to me. It makes me happy that I can make five knives out of a used, old Martha Stewart cutting board that was going to be thrown away. You would have never known that the wood was beautiful unless you started cutting into it.”